This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

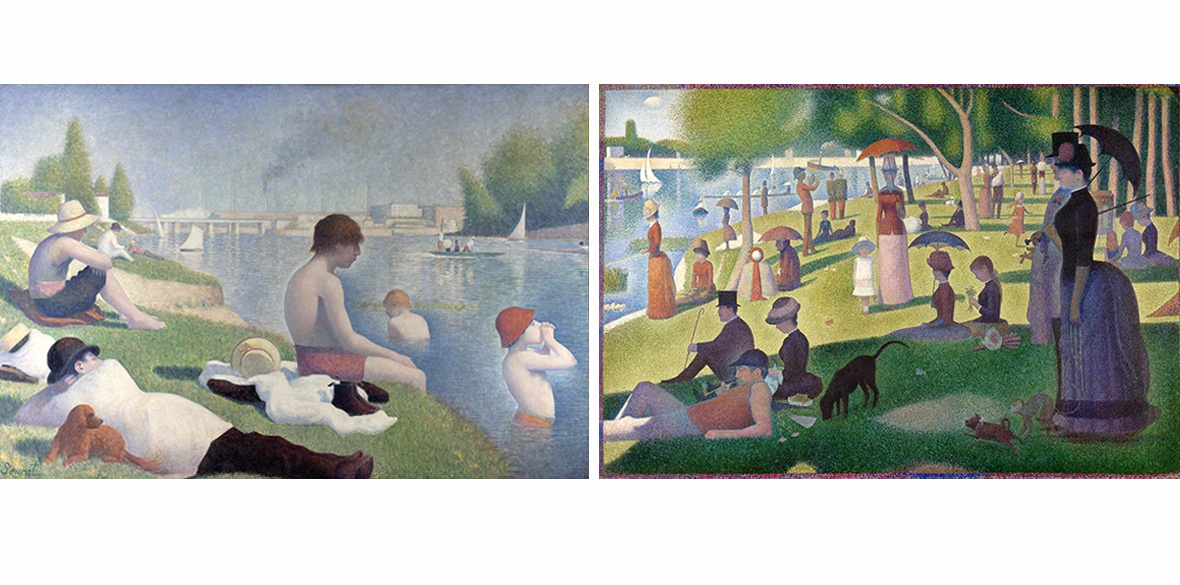

GEORGES SEURAT’S iconic The Bathers at Asnieres (1884) and its “companion” canvas A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1886) are probably among the best-known paintings by Impressionists.

But, unlike others, Seurat eschewed spontaneity for a meticulously scientific approach to colour and once memorably said: “Some say they see poetry in my paintings; I only see science.”

Early on, he had met and worked with chemist Michel-Eugene Chevreul, who had noticed that the perception of colour was not about the individual pigment but how the human brain processed adjoining colours.

Chevreul’s charts are made up of colour dots, which directly influenced Seurat’s technique of pointillism, where contrasting colours would be applied next to each other in small distinct “points.”

Initially, Seurat used the “balaye” technique of criss-cross brush strokes diminishing in size towards the horizon on The Bathers. But when he fully developed pointillism he retouched the canvas, using small dots of clear colours.

His approach had a conspicuous impact at a time when science was informing contemporary painting like never before. To Vincent van Gogh, Seurat was a “fresh revelation of colour,” while Camille Pissarro and later Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky used the pointillist technique extensively.

The Bathers at Asnieres, a working-class district in north-western Paris, depicts a group of workers relaxing by the Seine on a hot summer’s day.

Facing the river bank is the island of La Grande Jatte, the eastern tip of which is seen sloping into the Seine beyond the sailing boat on the right.

In the background, the Asnieres railway bridge and the factories of Clichy, where Seurat had his studio, complete the vista.

The Bathers and A Sunday on La Grande Jatte represent the polar opposites of of French society — ordinary working-class people are depicted in the former, while on the manicured lawns of the elegant Grand Jatte, the bourgeoisie parade.

In this pictorial class analysis the bathers, laid back and playful, are cast in a luminous light while half of the the figures on the Grand Jatte are engulfed in shade and display a preposterous social propriety.

The future, posits Seurat, lies with the working people — might the bathing boy in the foreground be mocking the “posh lot” across the river on the Grande Jatte?

Seurat, like his friend Camille Pissarro, was progressive and particularly sensitive to the plight of women and none more so than those employed in domestic service, prostitutes and “kept women,” such as the one in the foreground of the Grande Jatte.

He would uncompromisingly articulate these concerns in the great canvas Les Poseuses, painted in 1888. Tragically, three years later Seurat would die within a week of contracting diphtheria at the young age of 31.

Throughout his life he was a workaholic with little concern for own wellbeing or health. At the time he was also depressed by the recent suicide of his dear friend Van Gogh.

Seurat’s other close friend and fellow pointillist Paul Signac had little doubt that “our poor friend killed himself by overwork.”

His legacy remains a landmark achievement in innovatory aesthetics as well as in a profound sensitivity to social causes.