This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

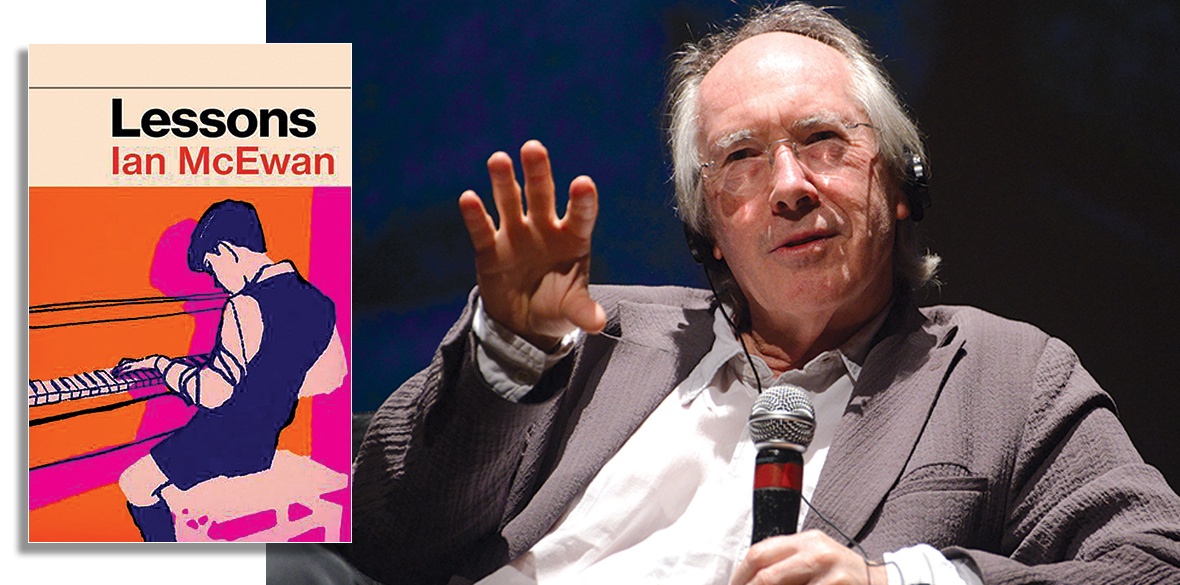

Lessons

by Ian McEwan

Jonathan Cape £20

LESSONS is a long novel for Ian McEwan (now 74) and it’s interesting for fellow British boomers to join central character Roland Baines on his journey through postwar childhood, 1960s boarding school, relationships, parenthood, through to old age and Covid-19 — yet struggling to find a meaningful life (Roland, not the reader).

It is also a tale of sexual abuse and emotional abandonment. A sadistic, emotionally unstable piano teacher at Roland’s boarding school seduces him – later inviting him to her cottage nearby.

Fourteen-year-old Roland – not wanting to die a virgin, should there be nuclear conflagration over Cuba, accepts. The sex is explicit. McEwan, as ever, juxtaposes lovely and nasty very well.

His “capture” culminates in marriage paper work for a registry office in Scotland, where it’s legal. Pulling himself from his addiction Roland gets away. The emotional damage is obvious, but not to him, until he confronts her in their old age after police turn up with their own paperwork.

His intelligence compromised, he flunks school and lives the life of a comfortable drifter; dabbling in poetry, writing the texts for greetings cards, playing piano in a hotel bar, tennis coaching, yet developing none of these talents.

“A fantasist” according to the wife who left him and their seven-month-old son to pursue a writing career.

She becomes an internationally feted novelist, with the inevitable emotional fallout for her son. But Roland has enough integrity and love left over to do a very good job as a single dad. Maybe nurturing the needy child in himself after his own mother abandoned him to boarding school?

Low-hanging fruit for a predatory teacher of course. Compensating for his violent army father? There is an early reference to his mother in law having once been employed by Cyril Connolly, editor of the literary journal Horizon, who famously said “There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.” McEwan doesn’t refer to this and I wondered if it was a subtle reference to be discovered, or an unconscious one on his part.

Roland’s story is set against global events, although surprisingly the Iraq war is missing. Dealt with in his 2005 novel Saturday? Where he all but condones the invasion.

There is a great deal of didactic writing, particularly with McEwan’s own bugbears, like Brexit, and he seems to abandon that well known creative writing edict, show not tell.

But then this is Ian McEwan, the great chronicler of muddle England, and writers of his fame and accomplishments can break any “rule.” Yet he tells too much, particularly the reportage of the inner lives of many of the characters. I found it hard to care for many of them – except Lawrence, the son. I wanted to know how he turned out. Well, as it happens.

The latter part of the book is set in south London where Roland ages with a typical boomer crowd who loathed Thatcher but benefited from the politics. They are “decent” centrists and Roland’s “decent” centrist Labour politics keeps him from veering too far into socialism.

A late love affair is cut tragically short, and we feel, well, this would happen to Roland, wouldn’t it? Would have been nice to give him a break. But this is McEwan, where things don’t turn out “nice.”

For McEwan, happiness rarely goes unpunished. Spoiler alert – Roland doesn’t even get to cast the ashes – in a scene that could be funny or cruelly gratuitous.

Lessons is a baggy novel, full of researched detail like postcodes, street names and historical reportage – quite unlike his Booker Prize winning Amsterdam (1998) and his celebrated and filmed Atonement (2001) where brevity and clear crisp language served the narratives brilliantly.

Written in tinder-dry prose, the novel sometimes ignites into lively passages. There is occasional Dostoevskian depth too, as Roland reflects: “In surveying a life it was inadvisable to acknowledge too much defeat” and it is in these kinds of observations that the novel becomes universal rather than particular.