This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

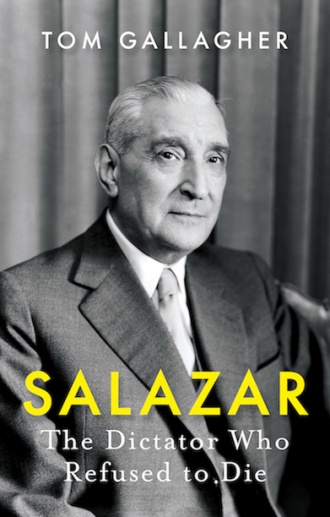

Salazar: The Dictator Who Refused to Die

by Tom Gallagher I Hurst Publishers £25

AS leader of Portugal from 1932 to 1968, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar was one of the most enduring dictators of the 20th century, wielding power through what his latest biographer, Tom Gallagher, identifies as a combination of “technical skills and acute political intuition.”

He came to his exalted position largely as a result of the terrible period that followed the 1910 revolution in Portugal, which ushered in a democratic republic but led to more than 15 years of political and economic chaos.

In 1926 a military coup tried to restore order and the army looked to Salazar - an economist, not a politician - to bring about some financial rectitude. He did such a good job that when he was eventually asked to fill the post of prime minister he could more or less name his terms, becoming absolute ruler in a bloodless coup of his own that turned the military dictatorship into a civilian one.

Although for much of his time in power Salazar was labelled a fascist, Gallagher prefers to characterise his 34 years of rule as those of an authoritarian “conservative nationalist” who often looked askance at the philosophies and actions of Hitler, Mussolini and Franco.

An austere, aesthetic man who was deeply uninterested in promoting a cult around himself or his party, he instead adopted a low public profile while expertly keeping the most influential sections of Portuguese society – the military, the catholic church, the landowning class and the intellectual elite – happy enough to allow him to continue on his way for as long as he liked.

Gallagher, who is emeritus professor of politics at the University of Bradford and has written a number of books on modern authoritarianism, argues that Salazar essentially saw Portuguese citizens as “naughty children” who needed to be kept in line, and that to a large extent the Portuguese people acquiesced in that relationship.

This, he suggests, led to a firmly paternalistic, rather than outrightly oppressive order that carried with it significant restrictions on freedom but not the levels of terror that other dictators of his era indulged in.

While he was by no means averse to using imprisonment, torture, military force or even assassination to maintain his hold on the country, he was never inclined to do so if he could find a neat, politically expedient way of doing so first.

Although Gallagher makes this case reasonably convincingly, sometimes his willingness to paint Salazar as a relatively benign “dictator with a difference” leads the book into unnecessary coyness.

Often, for instance, we are told that problems are “dealt with” by the authorities, but rarely are we given any of the gory details that would bring that brutal reality to life.

Likewise, while Gallagher is keen to tell us about Salazar’s impressive grasp of economic affairs and his ability to bring order to society, he is less forthcoming about the details of his long-term failure to look after large sections of society who really needed his help.

The stultifying poverty of the Salazar years, which led many to view Portugal as one of the most economically backward nations in Europe and encouraged emigration on a massive scale, is largely skirted over.

To be fair, the main purpose of the book is to examine the fascinating issue of how Salazar’s personal and political qualities allowed him to hold on to power for so long – and Gallagher does that well. But a slightly deeper consideration of the collateral damage connected to Salazar’s rule might have provided better context and a bit more balance.

In his laudable attempts at even-handedness, Gallagher sometimes appears to give Salazar too much benefit of the doubt.