This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

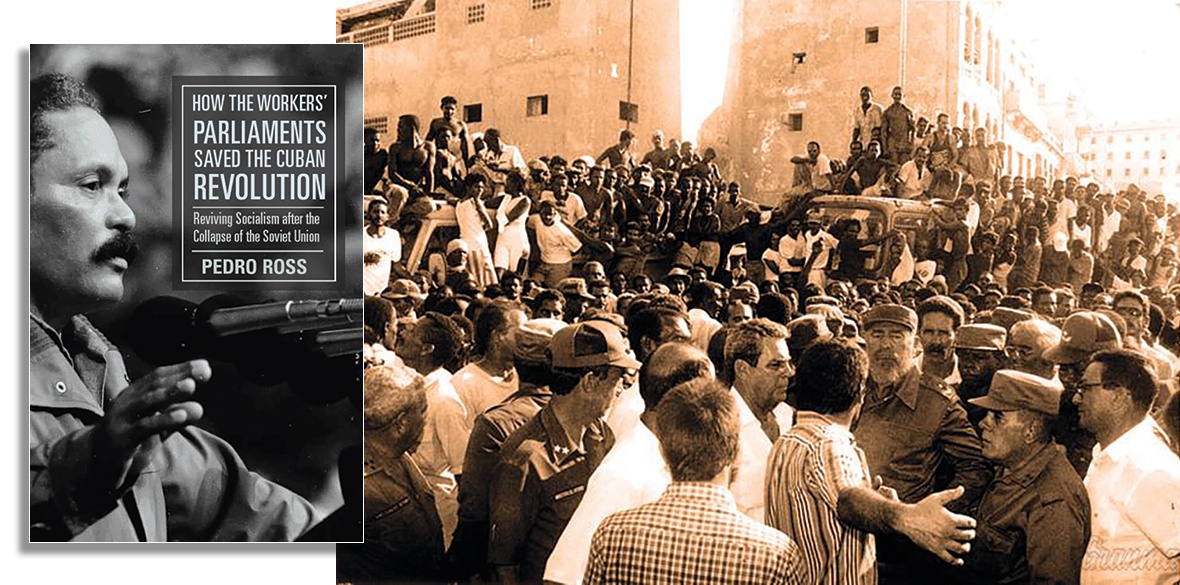

How the Workers’ Parliaments Saved the Cuban Revolution: Reviving Socialism after the Collapse of the Soviet Union

by Pedro Ross, Monthly Review Press Paperback, £14.50

CUBA’s survival as a small, independent, socialist republic following its revolution in 1959 is remarkable.

That survival is even more extraordinary following the collapse of the Soviet Union which, irrespective of its shortcomings, provided an umbrella within which socialist experiments could take place and which, in the case of Cuba, was its main trading partner throughout the blockade imposed by the United States.

This account by Pedro Ross, retired general secretary of the Central de Trabajadores de Cuba (CTC, the Cuban Workers Union, equivalent of Britain’s TUC) is a first-hand account of the consequences of that collapse for Cuba and how it responded.

Between 1989 and 1992 Cuba’s economy shrank by a third as production of goods and services disintegrated.

Imports fell by 80 per cent and there were enormous supply shortages — of food, water, power and transport.

All fuel had been imported from the Soviet Union, which was the major importer of Cuban agricultural products. Sugar prices collapsed.

This led to huge budget deficits, an excess of circulating money, an enormous black market (for example bicycles produced and sold for 40 pesos sold for 10 or 15 times this amount) and speculative activities.

These in turn led to significant internal unrest with demonstrations in Havana and elsewhere in 1994.

The consequence, acknowledged not least by Castro and other leaders (whose speeches are reproduced in the book) was a political and ideological crisis not just amongst ordinary people but within Cuba’s leadership.

A key element of Cuba’s response to these disasters — a “special period in time of peace” — was to reinvigorate its workers’ parliaments (first introduced in the 1980s), strengthening workplace democracy with a renewed emphasis on workers as their own employees.

For 45 days in early 1994 some 80,000 workplace parliaments engaged in intensive debate on what should change at every level from the workplace to the national economy.

Ross’s book consists of 80 short essays arranged in two parts. These encompass the historic and political context along with first-hand accounts of meetings in enterprises ranging from agriculture, cigar manufacture, hospitals, to milk and food processing, all described by Ross as a “vast school of economics” that includes self-education and policy decisions.

Workplace weaknesses included bureaucracy, overstaffing and absenteeism, lack of quality control to fulfil production targets, unnecessary reordering of supplies to maintain allocations, and an “absurd habit of consuming without justification certain allocations in order to ensure supply in the next budget cycle.”

At the level of the national economy debates fed in to a new economic understanding and Cuba’s opening up to foreign capital.

Possession of dollars was decriminalised and a retail marked in foreign currency developed, effectively establishing a dual financial system.

Self-employment and small-scale entrepreneurship was encouraged and state-owned agricultural enterprises converted to co-operatives.

The US of course anticipated imminent collapse and intensified its blockade and campaign of destabilisation including sabotage and biological warfare.

When this didn’t succeed it introduced the notorious Helms-Burton Act (1996 and still in force) which applies sanctions against non-US companies trading with Cuba, which therefore have to choose between Cuba and the US which is a much larger market.

Despite a brief and half-hearted relaxation under Barack Obama’s presidency, attacks intensified from 2017 under the Trump administration which in 2019 encouraged US citizens to sue third parties for “trafficking” property in Cuba expropriated after the revolution. This provision had previously been waived by every US president.

All of this continues under Biden.

Recent examples include a fine of $110 million (plus $3 million in costs) against a Norwegian Cruise Line for docking in Havana, which is still in US law “owned” by the Delaware-registered company Havana Docks Corporation.

The ruling that docking in Havana constitutes “trafficking in stolen property” is already leading to an avalanche of lawsuits.

That Cuba has survived all this on top of natural disasters — cyclones, floods and fires — in a country particularly vulnerable to climate change, is remarkable.

That it has done so at the same time as securing one of the highest literacy levels of any country in the world, maintaining a health service that is envied by large parts of the US, and providing aid to liberation movements elsewhere, is extraordinary.

The revival of workers’ parliaments represented a major renewal of deliberative democracy.

At the same time, Cuba’s continuing economic crisis has produced a social malaise that manifests itself in many ways. One of them has been a political detachment including a decrease in political and electoral participation.

Ross’s account of Cuba’s survival is at the same time an inspiration to everyone struggling for socialism, and a warning of the challenges to be faced in building it.