This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

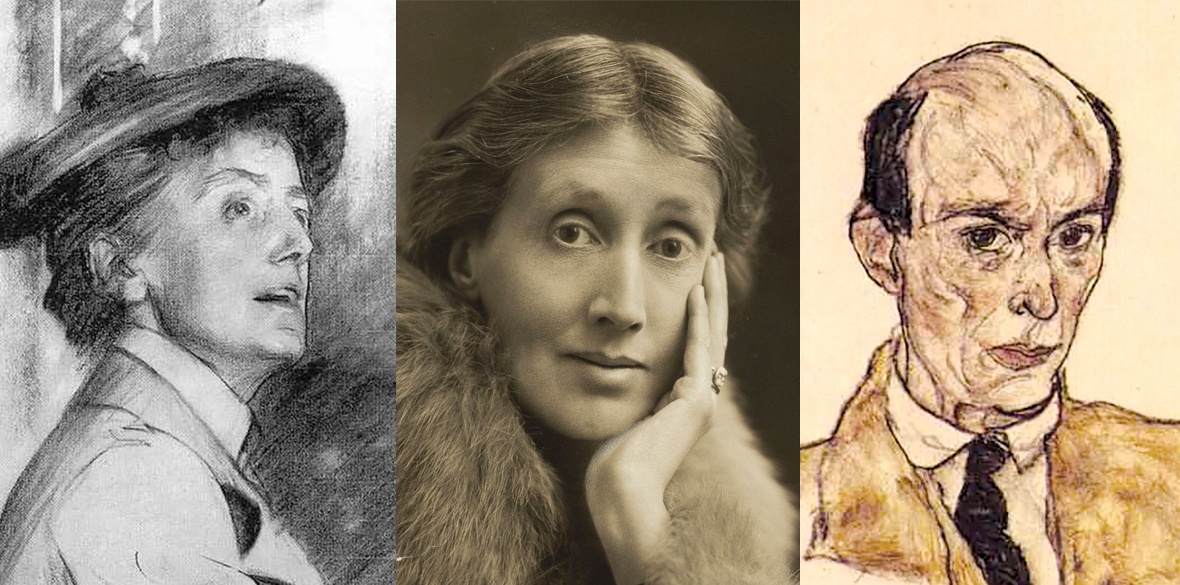

MANY of the early reviewers of Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) noted parallels between her literary innovations and those of contemporary composers such as Claude Debussy.

Woolf’s interest in music was overlooked after her death. But, 80 years on, we are now beginning to explore how her extraordinary experimental uses of narrative perspective, repetition and variation derive from her close study of particular musical works and specific musical forms.

Music provided Woolf — and other modernists including James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein and Katherine Mansfield — with a vocabulary to imagine and describe their creative practice and formal innovations.

Woolf compares her diary writing to a pianist practising their scales and describes her reading as a process of “tuning up” for her writing. And in 1940 she famously observed: “It’s odd, for I’m not regularly musical but I always think of my books as music before I write them.”

Woolf grew up immersed in music. As a young woman, she attended operas and concerts at the Royal Opera House three or four times a week, sometimes every night. Like most women of her age and social class, she had received basic music education in singing and piano.

But her passion as a listener far outstripped her abilities as a performer.

Her letters and diaries repeatedly convey her love of classical repertoire, particularly the works of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and Wagner. But she heard a wide variety of music in varied settings. She heard folk music as she travelled in England, Scotland and continental Europe and took in comic and patriotic songs in music halls.

She delighted in the work of Arnold Schoenberg and the avant-garde repertoire through her membership of the National Gramophonic Society, along with Russian ballet music when the Ballets Russes visited London in 1912.

Woolf’s Hogarth Press also published studies of contemporary music, composers and popular books of music appreciation. Her understanding of, and in some cases intimate friendships with, leading composers, music critics, conductors and other musicians of her time gave her an insight into professional musical life, too.

Friends included the composers and critics Eddy Sackville-West and Gerald Berners, the conductor and educator Nadia Boulanger and the composer and feminist Ethel Smyth.

Woolf’s feminism, pacificism and cosmopolitanism were significantly shaped by her enduring, passionate love of music. The social conventions surrounding music education, performance and composition catalyse some of her wittiest and most acerbic social comedy but also inform her critiques of, for example, women’s unequal access to music education.

In her first novel, The Voyage Out (1915), Woolf references specific musical works to challenge the established expectation that men and women should play different repertoire.

The novel’s female protagonist, an accomplished amateur pianist, plays Beethoven’s late piano sonatas, works frequently characterised as too technically and intellectually demanding for women performers. Essays addressed to amateur female pianists characterised the works as “simply unattainable.”

Music also influences Woolf’s creative innovations. The double-narrative structure of Mrs Dalloway, which contrasts and entwines the lives of society hostess Clarissa Dalloway and traumatised veteran Septimus Warren Smith, may well be modelled on the double form of musical fugues — “fugue” was a contemporary term for shell shock.

Woolf observed in 1909 that: “We are miserably aware how little words can do to render music.” But this difficulty frequently catalyses and becomes a subject of her writing.

It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, that her prose has been a rich source of creative inspiration for composers. Her work inspired Dominick Argento’s 1974 song cycle From the Diary of Virginia Woolf and more oblique responses, such as Max Richter’s music for the 2015 ballet Woolf Works.

In the last 15 years, musical responses to Woolf’s writing have proliferated, from the string quartet and songs premiered by the Virginia Woolf and Music project, to the recent announcement that composer Thea Musgrave is writing an opera inspired by Orlando.

In a 1905 essay, Woolf invited contemporary writers to draw inspiration from words’ allegiance to music and scholars of Woolf’s work and composers are now, it seems, doing just that.

Emma Sutton is professor of English, University of St Andrews. This article is republished from The Conversation, the conversation.com.