This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Dear Christine

Vane

Newcastle-upon-Tyne

AS A 13-year-old delivering newspapers in a Surrey village, I read about Christine Keeler on my paper round, gaining rudimentary political education comparing redtop and broadsheet headlines.

With that long lustrous hair, I thought Keeler beautiful and was intrigued that she’d had sex with a Russian.

It was the early 1960s and the sexual revolution was dawning. It was also the time of the so-called Profumo Affair, the political scandal which erupted when the brief fling in 1961 between John Profumo, secretary of state for war in Harold Macmillan’s Tory government and Keeler, a 19-year-old would-be model, came to light.

Profumo denied it but, after later admitting the truth, resigned from government and Parliament. The Tory Party was damaged by the scandal — there were rumours that Keeler may also have been involved with Soviet naval attache Yevgeny Ivanov — and it lost the 1964 general election to Labour.

Thus Macmillan’s government was brought down by a teenager, whose private — and legal — sex life hit the headlines.

Yet it was Keeler who was to burn in shame and, like Monica Lewinsky years later, will be remembered only for her sex life.

The fabulous — and free — Dear Christine exhibition in some ways redresses the balance.

It explores the fables surrounding Keeler in painting, ceramics, sculpture, music, film, poetry and performance.

Portraits capture that quirky overbite, high cheekbones and the vulnerability, with Natalie d’Arbeloff’s The Game — a grid of “significant others” — pointing up Keeler’s simultaneous power and powerlessness, while Sadie Hennessy’s Christine Keeler Cake has attendant hypocritical verbiage from 1960s matrons.

Marguerite Horner’s Paparazzi shows how Keeler was passed around the upper classes, just as she was in the dysfunctional family of her childhood.

Keeler had been iconised by the Establishment, who surely thought of her as their bit of rough.

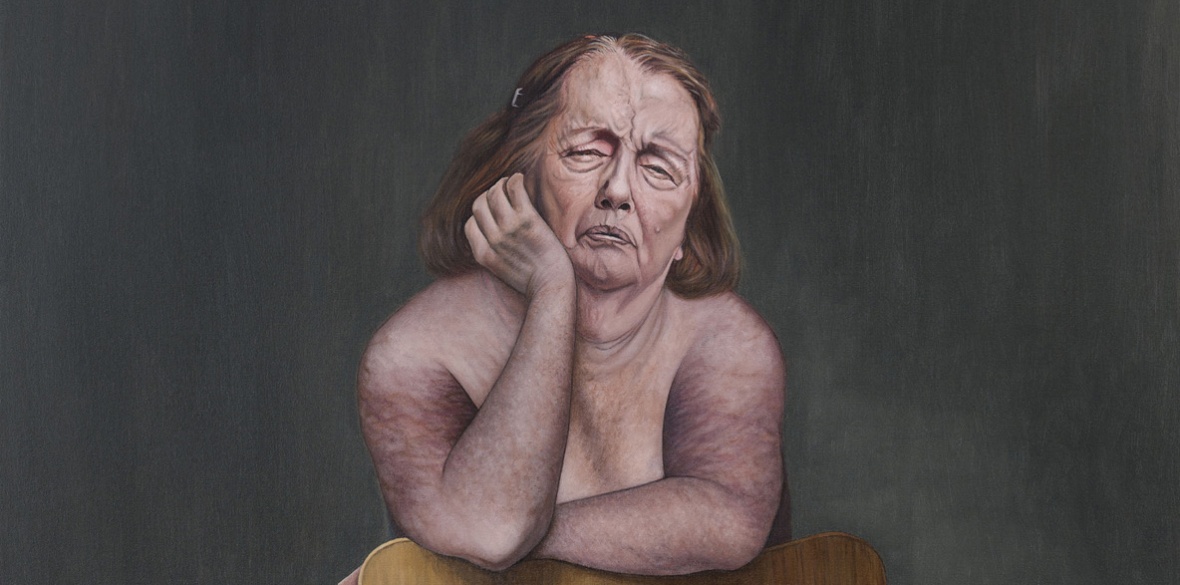

But, in Jowonder’s magical painting The Underworld of Zos, Keeler levitates herself from the lower orders into the “kissing circle of the elite,” showing them as the “low” ones. Sadie Lee’s painting of an ageing Keeler is poignant and well realised, as is curator and painter Fionn Wilson’s homage to her beauty, based on one of Lewis Morley’s portraits.

Pauline Boty, a founder of the 1960s British pop art movement, painted Christine in the now lost work Scandal 1963 and Caroline Coon pays homage to it with Christine Keeler: Anger, Blame, Shame, Ruin, Grief. There are also previously unseen photographs on show, courtesy of curator and friend James Birch.

The well-written catalogue includes a contribution from Keeler’s son Seymour — remembering what a good mother she was — and in it, Wilson points out that while Keeler is a significant figure in British history, there is little recent artistic reference to her.

“I wanted to add to the visual record of her life, which represents themes still relevant to this day including class, power and the politics of sex,” she writes.

“The participating artists are women who offer their own perspective on a narrative that has mostly been led by men.”

Indeed. Shame is the modern version of the stocks. As a woman behaving in a sexually free way, Keeler was shackled and this exhibition removes them.

Never mind the background of deprivation and sexual abuse, money-grubbing tabloids were to haunt her for the rest of her life, tracking her ageing.

Dear Christine channels Keeler through the lens of judgement, not of her but of the system that used her as a scapegoat and which was hypocritically outraged at her simultaneous sexual affairs — haven’t married men with lovers always had simultaneous sex? — with Profumo and Ivanov, whom MI5 were trying to “turn.”

Had Keeler been a honey trap and turned him in — as opposed to on — she too might have got an OBE, as did Profumo decades later.

There’s an old Chinese proverb: “Fame is the first disgrace.” Yet not everyone seeks it.

Dear Christine runs from June 1 until June 29, opening times: vane.org.uk and then tours to Elysium in Swansea and Arthouse1 in London.