This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

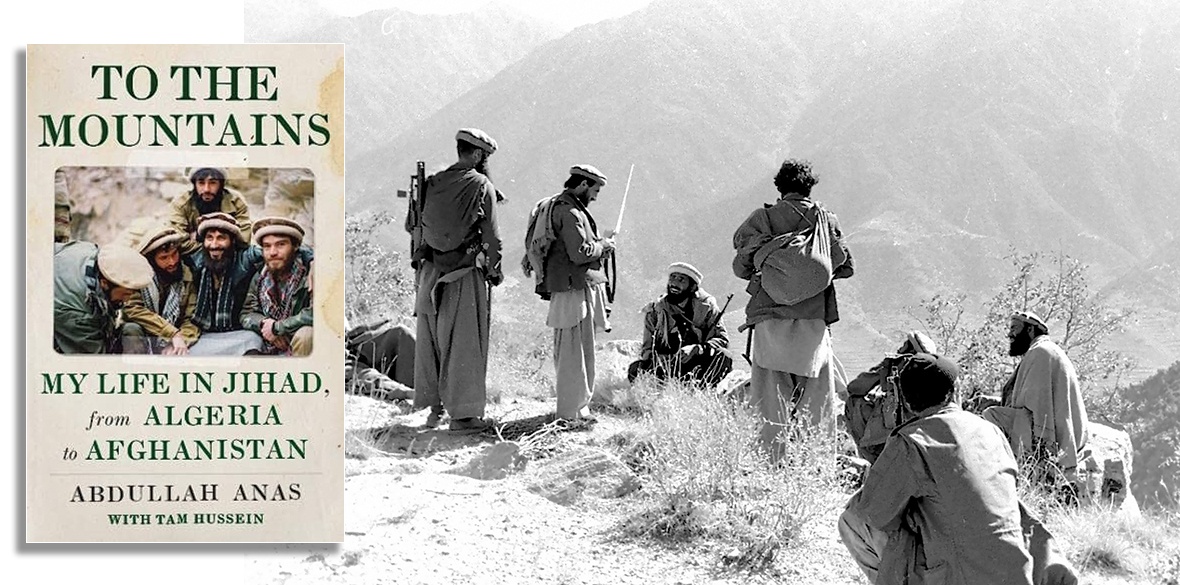

To the Mountains: My Life in Jihad, from Algeria to Afghanistan

Abdullah Anas and Tam Hussein, Hurst, £15.99

ALGERIAN Boudjema Bounoua, who adopted the nom de guerre Abdullah Anas, recounts his experiences fighting against the Soviets in Afghanistan during the 1980s alongside fellow Mujaheddin. Anas’s account is written in English with support from investigative journalist Tam Hussein.

Born in the late 1950s, during the Algerian war of independence, Anas relates how the experiences of his family and fellow compatriots, alongside a religious education, fashioned him into both an anti-colonialist and a devout Muslim. Later as a young man Anas answered the call of Jihad after a group of Islamic scholars issued a fatwa calling upon Muslims to expel the Soviets from Afghanistan.

During his time as a mujahid throughout the 1980s Anas rubbed shoulders with numerous fighters and commanders who would later shape Aghanistan’s future or become infamous on the global stage. These included the elusive Che Guevara-like guerilla fighter and future Afghan Defence Minister Ahmad Shah Massoud, future Afghan Prime Minister Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, as well Osama bin Laden and other individuals who would later form al-Qaida.

In addition to taking part in the fighting, Anas served as mediator and emissary between Massoud’s group and various other Mujaheddin factions whom he encouraged to maintain a united front instead of disintegrating into infighting. Anas also later became head of the Arab Services Bureau, whose role was to assist volunteers from Arab countries to partake in the Afghan Jihad whilemaintaining a non-sectarian stance and not falling foul of the numerous (at least 15) armed Islamist factions involved in the war.

Anas recounts with much despair how, despite his best efforts, the formerly (at times barely!) allied Mujaheddin groups were unable to agree to a power-sharing mode of government and slowly turned on each other after the Soviets left Afghanistan. This civil war only ended when the Taliban took over the country in the mid 1990s.

Anas thus explains how the Jihad (struggle) of nation building and maintaining peace was far more difficult than the martial Jihad of expelling an invader. The reader can feel Anas’s disappointment as he echoes the notion of “revolution” betrayed.

He also discusses how during the late 1980s the nature of volunteers coming to the Pakistan-Afghan border slowly changed from those seeking to “fight the communists” and support the Afghan people to those who espoused more extreme interpretations of Jihad and had no qualms denouncing or even killing fellow Muslims who did not share their religious interpretations.

Anas laments how the appearance and influence of these extremists corrupted a number of young Muslim men who later joined al-Qaida or went on to commit atrocities around the world. He strongly denounces these individuals, some of whom he knew and fought alongside, and explains how they later perverted the meaning of Jihad to excuse the murder of Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

Anas himself is unrepentant at having answered the call of a “just” (defensive) Jihad, a word he seeks to rehabilitate from the clutches of al-Qaida and which he describes as being a form of warfare guided by rules and limited to expelling an invader. He subsequently became both a target of Islamic extremists and an enemy of the Algerian state (who deemed him to be one of the former).

Under threat from both sides and unable to return to Algeria, Anas spends time in exile and eventually he and his family find refuge in London. In his later years, Anas returns to Afghanistan to try to mediate a peace agreement between the Taliban and Afghan President Hamid Karzai.

Readers may consider controversial Anas’s praise for his father-in-law Abdullah Azzam, an individual considered to have been bin Laden’s mentor.

Anas vehemently defends Azzam’s legacy characterising him as a venerable and charismatic Islamic scholar whose views were misinterpreted and perverted by bin Laden and his followers after the cleric’s assassination in 1989.

In this regard, it is difficult to ascertain where lies the boundary between Anas’s opinion and fact. It is also worth noting that while the reader may sympathise to varying degrees with Anas’s rationale for joining the Mujaheddin, alongside thousands of others, at the same time millions of his fellow Muslims did not answer the call of Jihad, including Afghans who fought against the Mujaheddin.

The reader will benefit from understanding Anas’s motivations for becoming a fighter and considering his experiences as a peacemaker. While To the Mountains is written for an English speaking and non-Muslim readership, Anas also has much to say to his fellow Muslims whom he warns against falling under the sway of extremism and whom he seeks to instruct about the importance of unity, nation building, and peaceful co-existence with those who do not share their views.

He advises: “The Muslim world can easily find martyrs, but what it urgently and desperately needs are statemen, negotiators, advisers, scholars and intellectuals who understand their times and peoples.”