This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

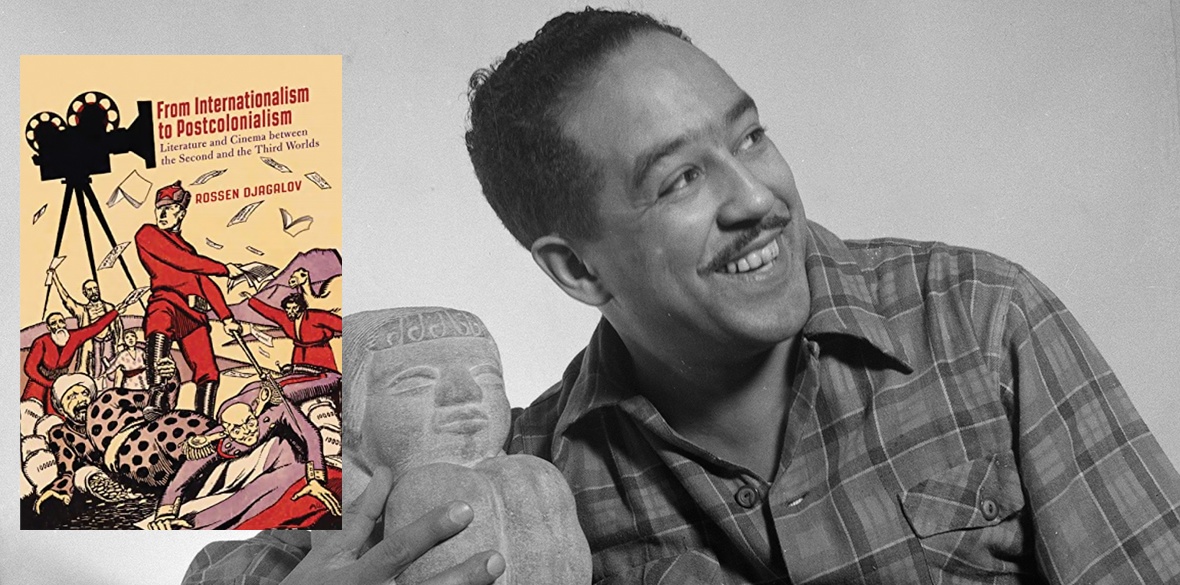

DESPITE the somewhat misleading subtitle of Literature and Cinema between the Second and Third Worlds, this fascinating text largely centres on the cultural relationships between the Soviet Union and what Vijay Prashad has termed the “third-world project.”

As Djagalov notes in his foreword, modern-day professionals in the former socialist world rarely show any substantive interest in Soviet-era achievements because that’s not where the money is.

Artists in third-world nations themselves are all too often embarrassed by the Soviet support that effectively helped kick-start their careers in a period when they were largely unknown.

By no means an uncritical admirer of the neoliberal project, Djagalov main mainly focuses on the Afro-Asian Writers' Association (1958-1991) and the Tashkent Festival for African, Asia and Latin American Film (1968-1988) to explore the surprisingly fluid and dynamic two-way relationship that sadly came to an end with the collapse of the Soviet bloc.

Despite what many pro-imperialist narratives would have us believe, the whole school of socialist realism is not reducible to a crude, didactic and one-dimensional outlook. The Brechtian idea of art as not only something which reflects the human condition but also as a weapon with which to change it, has produced challenging, exciting and adventurous works.

Although many commentators assume that the best of Soviet art came to an end after briefly flourishing in the early 1920s, one of the key strengths of this book is that it ably demonstrates how literature and cinema continued to develop in ways that were experimental and innovatory, all the more so in the post-Stalin period .

Soviet support for the arts was by no means restricted to narrowly political agitprop.The massive effort that publishers like Progress and Raduga put into the distribution of countless, cheaply priced and beautifully produced classics of world literature — and, interestingly, not just ones drawn from the Russian and Soviet canon — helped put these into the hands of first-time readers worldwide.

Nowhere was this more so than in the underdeveloped South and a strong focus on the art and culture of Soviet Central Asia was also very deliberate. Since the Toilers in the East University (KUTV) was established in 1921, Soviet power had combatted Tsarist oppression, Great Russian chauvinism and feudal obscurantism through land reform, the struggle for women’s rights , health programmes and literacy campaigns.

Held up as a showcase to other oppressed nationalities, the gains for ordinary people were huge and nowhere more so than in the field of culture, where many writers were published not only for the first time but in their own language and often in written scripts that didn’t exist before the revolution.

The relationship between the Soviet Union and “third-world” countries ought not to be seen as a one-way affair either. According to the UN, the number of books read per year by the average Soviet citizen was one of the highest in the world, and hundreds of Asian, African and Latin American writers found a huge and appreciative audience there.

In cinema — an art form of which Lenin was quick to grasp the immense importance — “world cinema,” for want of a better term, is still seen as something as a novelty in the West. But throughout the Soviet era, showing films from countries like India was common to the extent that it was to become one of the latter’s major markets.

Of course, these cultural interchanges did have shortcomings and outright tensions . A lack of clarity about what was being supported, and on what basis, meant that quantity rather than quality sometimes took precedence, as did a tendency to support initiatives on the basis of good intentions alone.

Sometimes the Soviet approach was somewhat narrow and mechanical and cultural internationalism, as in politics, was cut short by less idealistic geopolitical interests.

And the Soviet Union had its competitors. During the period in which Maoism began to label the USSR as revisionist, if not fascist, many accepted China's claim to be the new revolutionary epicentre.

Even on a smaller scale, the role of Yugoslavia in the non-aligned movement made sure that Soviet influence was not always uncontested, however moderately.

Djagalov covers all of this and more in a work that is interesting, detailed and original. Hopefully, it will inspire similar studies in the near future.

From Internationalism to Postcolonialism is published by McGill-Queen's University Press, £27.95.

STEVE ANDREW