This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

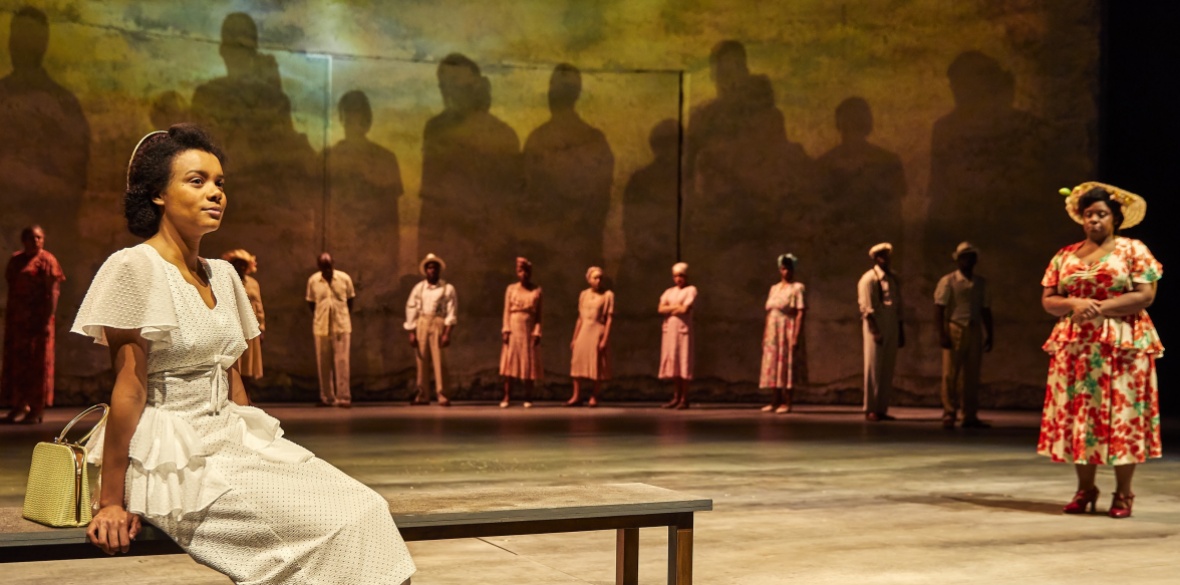

Small Island

National Theatre

ANDREA Levy’s novel Small Island was showered with praise and prizes when it appeared in 2004 and this dramatisation of it works hard to capture the luscious detail and superb characterisation of her work.

Technically, it’s an almost flawless production, with casting, choreography and set all spot on. But the heart is missing, or at least, it’s beating only very softly. Levy’s powers of description, rendered neat and tidy, miss out on her extraordinary control over what could have been a mere stream of consciousness but is, in the book, a forensic explanation of bewildering events.

A passage recounting that all-too-familiar happening during the Blitz, a doodlebug hitting the street, is reduced to a sentence or two. A necessary edit, perhaps, as this adaptation is more than three hours long, yet the exultation of a neglected wife discovering better sex is rendered in all its flamboyant detail. It’s perhaps a telling choice by Helen Edmundson, whose adaptation this is.

The quasi-Shakespearean plot embraces lovers found and lost and follows the fortunes of the feisty Jamaiacan emigres Hortense (Leah Harvey, flawless), determined to find the golden life she hopes for in the mother country and Michael (CJ Beckford), adored by all.

His wealthy parents send him off to school only to be dismayed when he returns, spouting Darwin and offending his God-fearing father. Finding another way out of the Caribbean is Gilbert (Gershwin Eustace Jr), a would-be lawyer who dreams of wearing the RAF blue and serving his king and country.

Awaiting them all in England is Queenie, brilliantly played by Aisling Loftus. She holds things together for her emotionally sterile husband Bernard (Andrew Rothney) and father-in-law Arthur (David Fielder), irreparably damaged by the first world war, and for her lodgers.

Her throwaway line: “I’m not ashamed to be seen walking in the street with you, not like some,” reveals a profound truth — that racism can be a choice.

Yet there are a few too many stereotypes here and that must invite questions about director Rufus Norris’s judgement. Levy’s humour has a sweetness and a delicate charm — it doesn’t require rolling eyes and sassy swaggering.

The ingrained racism which greeted the Windrush newcomers runs through Small Island like a polluted stream. There may be some motivations for it, with Bernard traumatised by an enforced spell in India during the so-called great Calcutta killings of 1946. He cannot bring himself not to hate a darker skin and Rothney finds nuances in a troubled man who starts as caricature and is revealed as a lost boy. But he’s a racist, nevertheless.

Levy’s resonant message, however, is as much about war and the promises it always makes that there will be a levelling of class and of race — promises that are always broken, along with the men and women caught up in it.

Runs until August 10, box office: nationaltheatre.org.uk