This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

LATIN American literature has seen an impressive renewal of the Gothic and fantastic genres in recent years.

Bolivian writer Giovanna Rivero is at the heart of that movement that also includes authors such as Argentinians Mariana Enriquez and Samanta Schweblin, the Peruvian novelist Gustavo Faveron Patriau, and Ecuadorian Monica Ojeda, to name but a few.

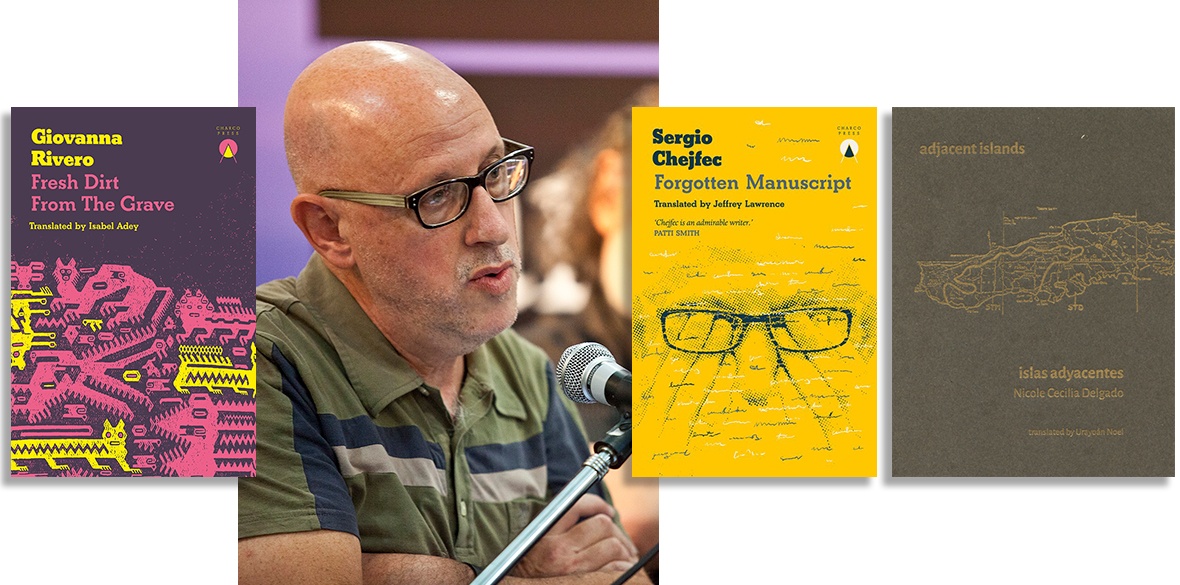

Rivero’s Fresh Dirt From the Grave (Charco Press, £11.99), translated from Spanish by Isabel Adey, is a masterfully crafted short story collection that fuses horror, sci-fi and social issues in equal measure.

The book opens with Blessed are the Meek, a dark story about Mennonites in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. This neo-Gothic tale of sexual abuse, religion, violence against indigenous communities and revenge has at its centre the teenager Elise, who will experience a dramatic event that will change her life forever.

“Elise sits up, smooths down the dress with giant flowers on it... overcoming the queasy feeling, she instinctively strokes the growth that was planted inside of her in a deep state of unconsciousness, like a bastard annunciation.”

Among my favourite stories in this arresting collection is Fish, Turtle, Vulture, a haunting tale of two young Salvadorian fishermen cast adrift for over 100 days in the shark-infested Pacific, and how one of them, the survivor Amador, recounts the story to the mother of his dead companion Elias Coronado.

“The sea was roaring, as if a monster was hungry too. That was what was going through my head. We’re all hungry, I thought. And I imagined all of humanity opening its mouth wide and the void gushing out from its throat like a volcano of acidic lava.”

An arresting book of stories by one of the most exciting writers from Bolivia, a book that has benefited from a well-crafted and meticulous translation by Adey. A must-read.

I began Argentine Sergio Chejfec’s Forgotten Manuscript (Charco Press, £11.99) a year after his sudden passing at 65.

The essayistic book, translated by Jeffrey Lawrence and first published in Spanish in 2015 as Ultimas Noticias De La Escritura, allows Chejfec to reflect on the physical act of writing and literature.

“This book can be read as the story of a notebook. One could call it a journal or a composition book — it doesn’t really matter — the important thing is that I’ve had it with me for a great deal of time,” explains the writer in the opening scene.

The essay, with its many footnotes and personal disquisitions is, at times, a narrative journey that guides the reader through conceptual modalities of experience and, at other moments, a monotonous analysis that drags on.

It covers many aspects of the process of creating a manuscript and the survival of digital writing, passing through the rituals many writers have when using typewriters or the solipsistic strategies of the visual arts.

As Lawrence explains in the Translator’s Afterword, Chejfec’s text: “is a difficult book to classify, straddling as it does the genres of autobiography and theory, scholarly monograph and ruminative essay, diagnosis of the digital and homage to the vanishing arts of manuscript culture.”

I enjoyed most of Chejfec’s dissertation, but I wish he had expanded even more on the autobiographical aspects of this essay, where I felt the writing was most luminous.

I have enthusiastically followed the work of Puerto Rican poet Nicole Cecilia Delgado.

Her latest book Adjacent Islands (Ugly Duckling Presse, £15), translated by poet Urayoan Noel, is one of Delgado’s “camping books” that she wrote “to record specific experiences observing the body in space.”

Delgado spent a few days camping in the Isla de mona (Amona), the third-largest island of the Puerto Rican archipelago.

The collection is divided into sections by day and written with a language that is simple yet powerful, revealing a place and a history under constant threat.

“Day 4, Wednesday, July 3/ I walk on countless cacti./ The island is this./ The trace of blood hunters leave behind/at season’s end,/ the garbage spewing from our rivers —/ paradise is polluted and we/ look the other way./ In Cueva de Lirio now,/ why does it have that name?”

A communal force inspires these few poems — they are as political as rebellious, looking at the untranslatable poetry of indigenous communities of Puerto Rico, among them the Taino.

In a letter to Noel, Delgado explains: “Over the past weeks, I’ve returned to thinking about the Taino and Taino-ness as a space of current political struggles and about the folx who are reclaiming indigenous rights in Puerto Rico, where we’ve bought into the lie of the root extinction of indigenous populations.”

Through her “camping poetry” experience, Delgado uncovers an island and its struggles as a space of hope: “Suddenly, one last vision/ of the beach and cave/ that were also/ our home.”