This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

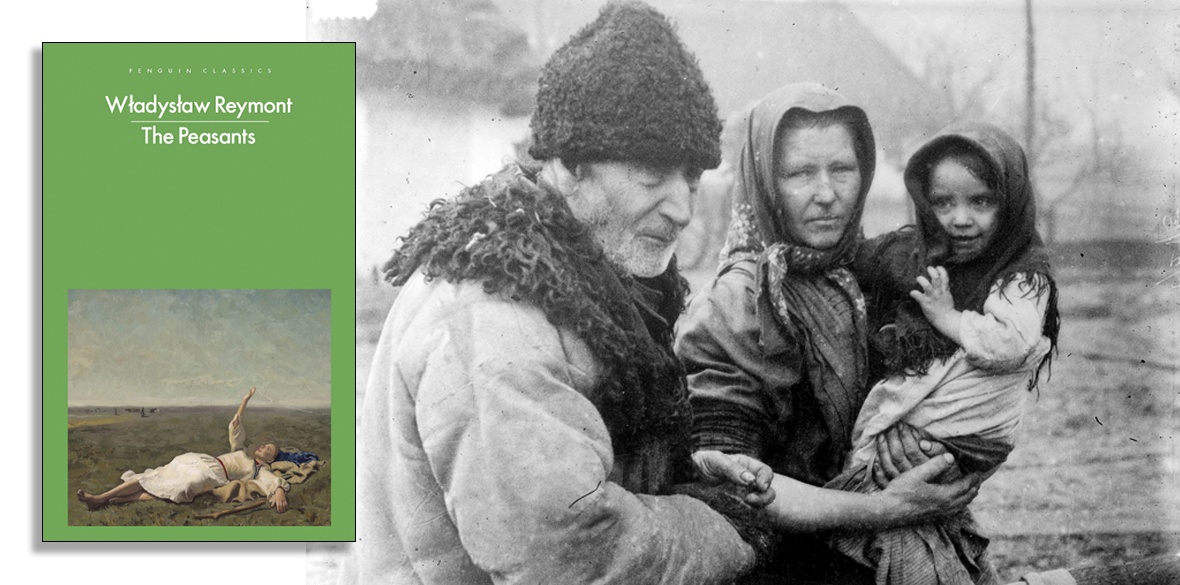

The Peasants

by Wladyslaw Reymont, Penguin Classics, 16.99

WLADISLAW REYMONT’s famous four-volume 900-page magnum opus The Peasants (Chlopi) has been translated into English for the first time, over a century since it was first published in the author’s native Polish language.

The novel, for which Reymont received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1924, is a fictional tale set during the late 19th century in the village of Lipce in Congress Poland — a part of the country under Russian control at the time.

The Peasants chronicles the goings-on within Lipce over the course of a year, with each volume corresponding to a season.

The main storyline revolves around the wedding between the village’s ageing and wealthiest farmer Maciej Boryna and the naive teenage beauty Jagna.

This marriage of convenience is brokered by Jagna’s mother’s desire to expand her family’s wealth and Boryna’s mistrust of his son Antek, who wants a share of his father’s land.

The marriage subsequently affects life within Lipce and its inhabitants in both direct and indirect ways and spurs discord, jealously and intrigue.

The English translation of Reymont’s work evokes a writing style akin to that of English novelist Thomas Hardy. Reymont’s vivid and detailed depictions of the novel’s numerous characters, the village and events such as baptisms, marriages, funerals and local fairs bring Lipce and its residents to life.

Likewise, his rich description of rural traditions, cultural practices and superstitious beliefs common at the time shine a light on a segment of Polish history now largely forgotten.

The small village of Lipce appears frozen in time in a post-feudal area where serfdom had been abolished only decades earlier.

Reymont’s work covers themes including peasant exploitation — we see the greatest exploitation is carried out by wealthy peasants owning small tracts of land against landless residents of Lipce (including sometimes their poorer relations) who are forced to earn a living as hired hands or beggars.

Reymont harboured political leanings towards the clandestine and nationalistic National Democratic Party that was active around the time he wrote his work.

Accordingly, the novel touches on the national question, namely that of Poland’s nationhood and independence from tsarist Russia.

However, Reymont does so in an indirect way (perhaps so as not to fall foul of tsarist censors who would otherwise have forbidden publication) and paints no romantic illusions about the possibility of nationhood.

Lipce’s peasants, many of whom are illiterate and struggling to survive a harsh winter, care little about Polish independence.

Indeed, we see that tsarist occupation has little effect on the day-to-day lives of Reymont’s characters whilst direct control over the unfortunates is wielded by wealthier peasants and the local Polish landowner, who at one point manages to channel away peasant anger by appealing to nationalist sentiment.

However, not all are fooled, as one peasant retorts: “I know what that Poland of theirs means: nothing but serfdom, oppression and a whip to your back.”

Aware that oppression can be imposed from within as well as without, our peasant adds: “In Polish times their only care for the people was to drive them to labour at the end of a whip and oppress them, while they partied until they’d partied the whole nation away.”

Land is a major theme in the novel such that the fields themselves are elevated to an almost sacred level, with the apogee of success and happiness in the eyes of the novel’s characters being to own at least a small piece of the farmland.

Reymont’s description of peasant life in 19th century rural Poland is a brutally honest account — at times humourous but often bleak and gruesome.

He does not hold back in his description of the challenges and brutality peasants faced, especially female characters trapped in abusive relationships or facing the dire consequences of having a child out of wedlock.

Religion is another powerful theme that echoes through the book. While we see the church’s pervasive power, reflecting the deep religiosity prevalent across 19th century Poland, the village priest’s threats of everlasting damnation issued from the pulpit do little to stop some of Lipce’s residents from partaking in all manner of vices, including an older woman’s attempt to seduce a young trainee priest.

Reymont’s numerous and colourful characters provide ample intrigue and contribute to a great many subplots throughout the novel.

While being crude, superstitious and largely oblivious of the world outside their village, Lipce’s peasants are also imbued with noble qualities and a naive innocence that arouses sympathy and respect from the reader.

It appears that one way Reymont gets away with raising controversial issues and criticism of authority is by couching these ideas within his characters’ dialogue — occasionally an uneducated and plain-speaking peasant accidentally issues a pearl of wisdom or a surprisingly enlightened critique of society.