This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

EMANUEL GOMES came to London seven years ago to find a secure job with a decent wage. In one of the richest countries in the world, he expected workers to be paid properly and their rights protected in law.

But instead he found himself trapped in the gig economy, fighting to keep his hours on precarious contracts, with little left over from the costs of living in London to send back to his family in Portugal and Guinea Bissau, West Africa.

In February 2018, Emanuel started working in the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) offices in Westminster as an agency cleaner. He was paid the minimum wage and lived with the constant fear of being laid off. Only entitled to statutory sick pay – £19.37 a day and nothing for the first four days – Emanuel would often work even if he was ill because he could not afford to take time off.

In April, at the height of the pandemic, he became very sick, but continued going to work. On April 22 he was so feverish he didn’t know where he was and had to be taken home from the office by a colleague. He died the next evening alone in his house.

As a black African man with diabetes, Emanuel was in the at-risk category and he should not have been working during the pandemic. But he was compelled to, not just by his employer, but by the MoJ – the administrator of justice in Britain – because he couldn’t afford not to. He was one of 25 cleaners at the office, and probably one of thousands across the country whose lives were valued below the hard work they carry out.

For the past few months I’ve been following the stories of cleaners working through the pandemic. Low-paid, outsourced and deprived of a safety net, cleaning staff are unfortunately used to being treated as disposable – but during the Covid-19 crisis these conditions took on a whole new cruelty, especially in one of our government’s very own offices.

Forced to clean an empty building

While Britain went into lockdown on the instruction of PM Boris Johnson, cleaners continued going to the Ministry of Justice offices on 102 Petty France, central London, as normal. Footfall had dropped from 3,000-5,000 a day to around 100 with almost all the ministry’s civil servants working from home. This meant there was roughly one cleaner for every four office workers.

Despite this the MoJ told its contractor OCS – the outsourcing firm that runs cleaning, catering and security services at Petty France – to keep staff coming in to clean the near-deserted building.

For Emanuel and his colleagues, the beginning of the crisis was a terrifying and confusing time. By mid-March, Covid-19 had begun to spread across the country, its epicentre in the capital. Europe was rapidly locking down, planes had disappeared from the skies and ICU beds were filling up with severely sick Covid patients.

Each day the cleaners – a team of around 25 South American, Spanish and West African migrants – saw fewer and fewer civil servants, until one day they were gone. But still they had not been told by OCS how they should work, what to do if they felt ill or if they were even classed as key workers.

Just before lockdown, two cleaners had already started to display coronavirus symptoms. Luis Eduardo Ventimilla, who has worked at the MoJ for six years, developed a cough and headache soon after a colleague came down with similar symptoms. His colleague continued to go into work until he was too sick to leave his bed.

“You have to imagine they are really really ill, because if they are sick they go to work anyway because they need the money,” Luis, who came to London eight years ago from Ecuador, tells me.

“And after that I was really worried so I went to talk with my manager to plan to do a meeting – she told me everything was fine.”

On March 23 – the day Britain officially went into lockdown – Luis Eduardo decided to self-isolate, also fearing for the safety of his wife who is asthmatic. Considering the building was near deserted, and hearing nothing to the contrary, Luis Eduardo also assumed he was not an essential worker. He tried to track down his supervisor to tell them he was leaving but couldn’t find them.

Instead he emailed the manager to inform them of his absence and to raise his concerns. “It is at this time we need clear concise leadership from management,” he wrote in a letter seen by the Morning Star.

“Nothing has been communicated to me on what steps to take, except that which is on the news. Why haven't we been provided with masks? Are you going to set up a special rota so that not everyone comes in at the same time?”

In response the manager tells him he will be recorded as being absent without leave if he doesn’t go through the official company procedure. She also tells him that masks are not necessary.

It wasn’t till March 25 – two days after the country had officially gone into lockdown – that Luis Eduardo eventually received a letter from OCS informing him that he was a key worker. The letter was dated March 20.

He was then sent another letter, this time from the MoJ reading: “This letter is confirmation that you are designated as a ‘key worker’, as referred to by the Prime Minister in his announcement and press conference of March 18 and your role is essential in the running of the justice system.”

Fatima Djalo, another cleaner, continued to go to work throughout the pandemic. A few weeks into the lockdown, OCS split the day team into two groups of six to come in on alternate days. However she tells me that this only lasted for about a week.

“At the beginning all we had was gloves, we didn’t have any disinfectant, any masks, we were just there on our own, cleaning up and down,” she says. “We just knew a little bits of information.”

Fatima, who has worked at the MoJ since 2009, came to England over a decade ago via Portugal from her home of Guinea Bissau – the same country as Emanuel. They both arrived in London alone with the intention of working hard to send money home to their families in Portugal.

Fatima’s fears of going in each day were heightened by the fact that her role had become completely redundant. “We are not cleaning anything because we’ve already cleaned everything!” she exclaims.

“We’ve cleaned the halls, we’ve cleaned the doors, we’ve cleaned the tables so we get in and they tell us to clean it again so there really isn’t anything to clean! We come in at 8am and we stay sitting down somewhere till 5pm. It makes no sense – it’s ultimately to punish us because if we don’t come in we don’t get paid and we cannot eat.”

She repeatedly asked for masks, but was told she could buy one herself on Amazon. At one point the staff were given a letter suggesting they could come into work using a bike or Uber. When Fatima asked if they would pay for the Uber, her supervisor said: “Well that’s not what it says. It was a suggestion, ‘why don’t you get an uber’?”

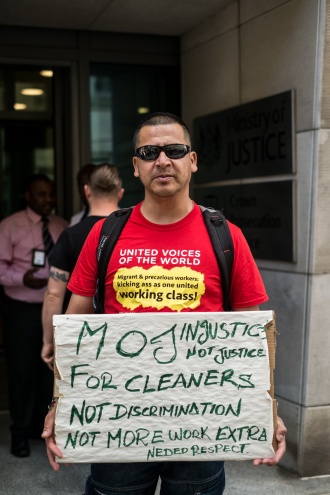

The cleaners’ union United Voices of the World (UVW) believed it was not necessary at all for workers to be sent into the buildings. UVW rep Molly de Dios Fisher tells me that around five cleaners fell sick during April and March with suspected Covid and two were off work for over a month.

“What they should have done was reduce the workforce, and have a handful of workers who were not in the high-risk category come in and do a deep clean once or twice a week with adequate PPE and with the appropriate health and safety measures in place,” she says.

“But instead they had workers coming in at peak times on public transport, cleaning in central London and working in unsafe conditions that contravened much of the advice we were receiving from government guidelines.”

On April 23 UVW sent a letter to OCS and the MoJ raising grave concerns by members that “they are putting themselves and others in serious and imminent danger of catching and spreading the potentially deadly Covid-19.”

The union claimed staff had still not been given proper PPE and as OCS had not offered more than SSP, workers were being left with “no choice but to work when ill,” even in the midst of a pandemic.

Emanuel’s death

Emanuel died at the age of 43, the same evening UVW sent the letter. Describing Emanuel’s condition in the days before he passed away, his friend Amadou said: “He would never miss work when sick, and in the last few days he was really ill. He had lost his appetite and wasn’t eating, he had phlegm and seemed to have a fever. When we got to Victoria station he didn’t even know where he was.”

That week cleaners also heard of the death of another worker in the building. Kier, a company that provides maintenance staff in the MoJ office, confirmed to me that one of its employees, an engineer, had died from coronavirus. However cleaners were repeatedly told by OCS supervisors that both men had not died from the virus, despite them having no knowledge either way.

“The whole situation gives you goosebumps because of how neglectful it is,” Fatima tells me. “Emanuel is dead and no-one knows if it was coronavirus or not and we are just sitting there unknowing.” Although Emanuel died on April 23, his colleagues were not informed of his death till the following week.

Because of Emanuel’s coronavirus-like symptoms, his friends and family feared he had died from the virus. However his death was officially recorded as hypertensive heart disease – high blood pressure – in a post-mortem report (not issued until eight weeks after Emanuel passed away).

But a representative of the family told me that it was not clear from the report if a Covid-19 test had actually been carried out. As a result the family are considering requesting an independent post-mortem report.

A culture of fear

Luis Eduardo was off sick for six weeks. For much of that time he was bed-ridden and at one point, his wife Stephanie had to call an ambulance to the house. “I had to sleep with one eye open to make sure he was breathing,” she says.

The paramedics discovered his oxygen levels were low but managed to stabilise him. They told them it was clear they both had coronavirus. During the time he was off work, OCS only paid him around £300. Stephanie tells me that without her salary, she doesn’t know how he would have survived.

Luis Eduardo eventually recovered after six weeks of fluctuating ill health at the end of May. He was then wary to return to work knowing that two workers in the building had died, and few precautions had been taken to protect staff. “I was afraid,” Luis tells me.

“They make us feel that we don’t have any value and that they don’t care about us. They just use us to get their money but they don’t offer any prevention measures or protect us or our health. I could have died here and nothing happened and that is very serious in a government office.”

But for Luis Eduardo, this treatment was unfortunately nothing new. For the past two years, Luis has been fighting as a member of UVW for occupational sick pay and the living wage. When he first started at the MoJ he was paid the minimum wage, which was then increased to £9.08 per hour following strike action last year.

However Luis Eduardo believes his involvement in the union has made him a target. Over the past few years he faced three disciplinaries, once for being off sick when he had informed supervisors he was ill. These incidents have caused immense stress for the pair, putting a strain on their relationship and at one point, causing Luis to develop a stress-related illness.

Other workers are on even more precarious contracts by third-party subcontractors. These temporary workers can pretty much be fired at will, which serves to generate a constant sense of uncertainty for staff. Emanuel was on such an agreement for two years before he was employed by OCS in February 2020.

But when he was moved onto the new contract, he found out that OCS had cut his hours by half. Because Emanuel was so afraid of losing his job, and had limited English and Portuguese language skills, he didn’t often speak up against management.

Following complaints by his friends, OCS restored Emanuel’s hours but split them into two shifts a day: one between 6pm-10pm and another at 6am to 10am. This remained unchanged in the months prior to his death, meaning he was forced to travel on public transport not two but four times a day.

"They run a culture of fear,” Molly says. “They prey on people who they know are susceptible to that fear. Emanuel spent most of his employment at the MoJ as an agency worker with even less job security than those outsourced to OCS. Emanuel could not afford to lose this job, and OCS preyed on and cultivated the fear that he would.”

Terms and conditions decide who lives and who dies

It’s not just at the MoJ offices where cleaners have been denied PPE, furlough and treated as disposable. Unions UVW and the Independent Workers of Great Britain – which both represent predominantly migrant workers in precarious jobs – have been battling with a range of unscrupulous outsource firms to prevent mass dismissals and provide PPE.

One of these was commercial services firm Cleanology, which laid off around 100 staff at the beginning of the crisis before rehiring them around two months later. IWGB claimed this was a way for the firm, owned by former Tory candidate Dominic Ponniah, to avoid risky furlough payments. Ridge Crest, a cleaning company contracted by London school Ark Globe Academy, was found bribing staff with offers of PPE in return for “dropping the union.”

While in another government building, the House of Commons, around 60 cleaners were denied the option of furlough and forced to clean the empty halls. This order came down from Cabinet Minister Michael Gove, according to Open Democracy. It reported that the staff were taking annual leave to avoid going into work, before they were granted the option of going in on alternate days for full pay.

IWGB president Henry Lopez, who worked as an outsourced porter at UCL for many years, describes cleaning firms as “some of the worst” in the country, and has seen exploitative practices such as withholding wages exacerbated by the crisis.

Some of the cases he has worked on during the crisis include cleaners who were sacked for refusing to work without PPE, a pregnant woman with a 70-year-old mother who was told by her employer she was not allowed to shield and many others whose hours have been slashed.

“It’s not just the worry of working through the pandemic, but also of not being able to pay their rent and bring food to their tables,” he explains. “They know these people are vulnerable and they have a system in order to abuse that situation. They treat them like disposable workers.”

At University College London (UCL), cleaner Maria Danery was let go by her employer Sodexo at the end of March, along with 30 other staff. Maria tells me the move made her feel “deeply sad,” after she had risked exposing herself to the virus by cleaning the student residence halls.

“We were especially afraid because we knew that there were potential students with symptoms of coronavirus and we would persistently request from the company to provide us with masks but they would tell us that this was something that was not required or necessary,” she tells me.

“So we were extremely afraid for our lives and then we were let go.” Maria also has two other cleaning jobs, one of which has deducted her annual leave during the time she was told not to return to the building.

“I think that they have taken advantage of this situation, because there is a constant situation of abuse,” she adds. Maria was offered work again by Sodexo a few days later after an intervention from her union IWGB. Similar to the MoJ, Maria says she was told very little information by her employers at the beginning of the pandemic, and is still waiting for notification of the Covid-19 crisis.

In March UCL brought in “special leave” for all contracted workers who needed to self-isolate, which would give them full pay. IWGB union organiser Jordi Lopez-Botey tells me these measures were implemented after members refused to go in. Because of this, Jordi says there have been far fewer cases of Covid-19 among UCL staff than other workplaces.

“This is how you can see how the terms and conditions of employment actually decide who is going to live and who is going to die,” he says.

UCL and Sodexo deny that any staff were dismissed during the pandemic and insist that workers were given appropriate PPE. Dr Matthew Blain, executive director of UCL Human Resources, said: “UCL values our cleaning colleagues who have played a vital role in keeping our campuses open and safe. We know that these are particularly worrying times and that’s why we have implemented a range of measures to ensure that these vital workers receive the same, or equivalent pay and core benefits, as directly employed staff.”

A Sodexo spokesperson said: “Any members of the cleaning team who have not continued working at UCL or we were unable to redeploy to other sites were included in our furlough scheme, including those on casual agreements.”

Outsourcing and racial discrimination

Unions have long battled the practice of outsourcing, claiming it exploits low-paid workers through downgrading contracts, and creating a culture of unaccountability with contractors and clients shifting responsibility between them.

However UVW also argues that outsourcing is not only exploitative but discriminatory, owing to the fact it often condemns largely migrant and ethnic minority workers to inferior terms and conditions than in-house staff. “It creates a two tier workforce,” Molly explains, where predominantly white staff enjoy better conditions than a largely BAME workforce.

During the pandemic the potentially discriminatory practise of outsourcing has taken an even greater precedence. Poor working conditions have not only been shown to reduce people’s quality of life but also their chances of surviving Covid.

Black males are four times more likely to die from the virus than white men – one factor being job insecurity as BAME people are more likely to work in front-line roles in precarious contracts that compel them to expose themselves to the virus.

Denial and accountability

Despite the significant number of infections in the building, and the deaths of two workers at the Petty France site, the MoJ claims there is “no evidence to suggest there is or ever has been a coronavirus outbreak” linked to its offices.

A spokesperson said: “We are grateful to all our contracted staff for working throughout the pandemic to make sure our buildings are safe for those who need to use them.”

OCS has also maintained that no staff tested positive for the virus, however the workers fell sick when there were very few tests available. In a statement, OCS said its practices had been in accordance with Public Health England guidelines, which states that masks are not needed unless workers are in infected areas.

But without the knowledge of who was infected and little attempt to make temperature checks, this was not possible to ascertain.

Earlier this week the MoJ announced that staff who were off sick will receive full pay backdated to April 1. But this falls far short of the cleaners’ two-year demands for occupational sick pay and the London living wage.

Calls are now growing for an independent investigation into the events that led to the spate of infections and deaths of outsource staff in the MoJ with shadow justice secretary David Lammy and Labour MP Lyn Brown (Emanuel’s MP) leading the call.

Explaining why he wants to see the MoJ and OCS investigated, Mr Lammy said: “These tragic deaths raise serious questions about the treatment of cleaners during the pandemic that the Ministry of Justice must answer.

It is totally unacceptable to force front-line workers back to work without the proper protective equipment and then to deny them the support they need when they get ill. There must now be a thorough investigation to assess what mistakes were made.”

The calls come three months after Emanuel passed away. His story realises fears long held by migrant workers and trade unions – that precarious work not only reduces quality of life but puts it at risk. If we are to learn lessons from this crisis, we must reverse the erosion of work rights propelled by practices like outsourcing, starting with implementing proper sick pay for all.

Some names have been changed or surnames removed to protect their identities.