This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

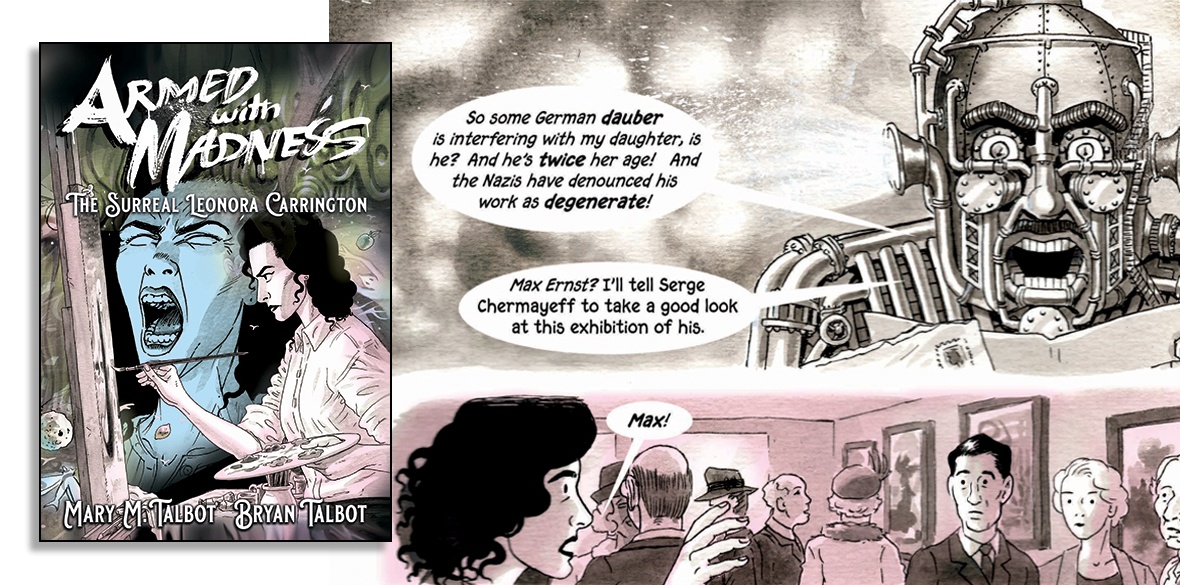

Armed with Madness: The Surreal Leonora Carrington

by Mary M Talbot and Bryan Talbot

SelfMadeHero, £19.99

HAILED as “the last of the surrealists” when she died in 2014, Leonora Carrington’s paintings and sculptures display her unique use of symbolism mixing influences from Catholicism, Surrealism, early Renaissance techniques and Aztec and Mayan mythology, in a unique blend of subtle colour and expert draughtsmanship.

Advancing from the male-oriented focus of the Surrealists, Carrington’s work explores the role of women, often in domestic settings, elevating it to the realms of the sacred.

Like the work of other female Surrealists, Carrington’s work resonates much stronger in the 21st century than her male contemporaries.

And Carrington’s life was as fascinating as her paintings.

Born in Lancashire in 1917 into “new money,” Carrington rebelled against her privileged background to study art in London where she became part of the Surrealist Group, starting a romantic relationship with Max Ernst.

She and Ernst moved to Paris, rubbing shoulders with Picasso, Duchamp, Eluard and Breton.

They then retreated to the Ardeche where, with the outbreak of World War II, Ernst, a German national, was detained, leading to Carrington experiencing a psychotic breakdown, which informs her work.

Armed With Madness possibly takes its title from Occultist Mary Butts’s 1928 novel of the same name, and like in the novel, the graphic biography suggests that isolated from the outside world one can experience a “reality more real than reality,” a goal of the Surrealists.

'The graphic biography claims that through her psychosis Carrington experienced this hyper-reality which then informed and improved her work and consolidated her style

This violent experience is shown through a change in colour-wash to blue-green, and by depicting the artist as totems from her work: horses, birds and mythical creatures.

And there is something to this suggestion of metanoiac change. Although many of Carrington’s famous pieces are from before 1940, her recognised style developed directly following this experience.

Meanwhile, Carrington fled to Spain, where she was interred in an asylum, before eventually fleeing Europe for exile in Mexico, where she became a national treasure.

With such an interesting life and work, why have most people in Britain not heard of Leonora Carrington? Why is Carrington celebrated in Mexico and not in Britain?

Does this reflect the ongoing misogyny of the art Establishment? Is Carrington’s rejection of her class background significant?

Armed with Madness considers these questions, in different degrees, covering the events of Carrington’s life at a fast pace, focusing on only the vital details, but still managing to achieve some depth, exploring important themes of her life, work and times: misogyny, class and madness.

Carrington faced misogyny from the Surrealists, whose ethos of equality, progressive thought and rejection of conventionality was contradicted by their treatment of women as mere muses and “femme enfants.”

Carrington rebelled against such “bullshit” stating: “I didn’t have time to be anybody’s muse … I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to become an artist.”

The rebellion against her family was one against her upper-class background.

Carrington’s father was the primary shareholder in ICI, and for all her rebelliousness she remained financially supported by her father for some time, even if she did not see him from the age of 20.

Armed with Madness does not shy away from depicting Carrington’s “rejection” of her class background, while still benefiting from its trappings.

Surrealism was a communist movement and the question of class in the 1930s and ’40s included the Stalin/ Trotsky split which divided the Surrealists.

Armed With Madness does not show Carrington’s position, and in fact it is not clear if she had one, but it does depict the individual members of the group’s frustration with Breton’s communist dogma and the tensions between the members who take either side, depicting Leonor Fini destroying Ernst’s portrait of Carrington after they had invited Tristan Tzara, a Stalinist, to stay in the Ardeche.

Publishers SelfMadeHero pay us a great service with this book, by bringing to popular attention important figures from the past in a quick and accessible way, while managing to illuminate themes vital to our times.