This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

COLDITZ is usually the name that springs to mind when people think of the POW camps housing Allied wartime detainees. But that WWII castle, full of “heroic” white inmates, is very different to the one at Ruhleben.

In the first world war, the disused racecourse on the River Spree outside Berlin was home for 300 British civilians who happened to be a so-called ethnic minority and in Germany at the outbreak of the conflict.

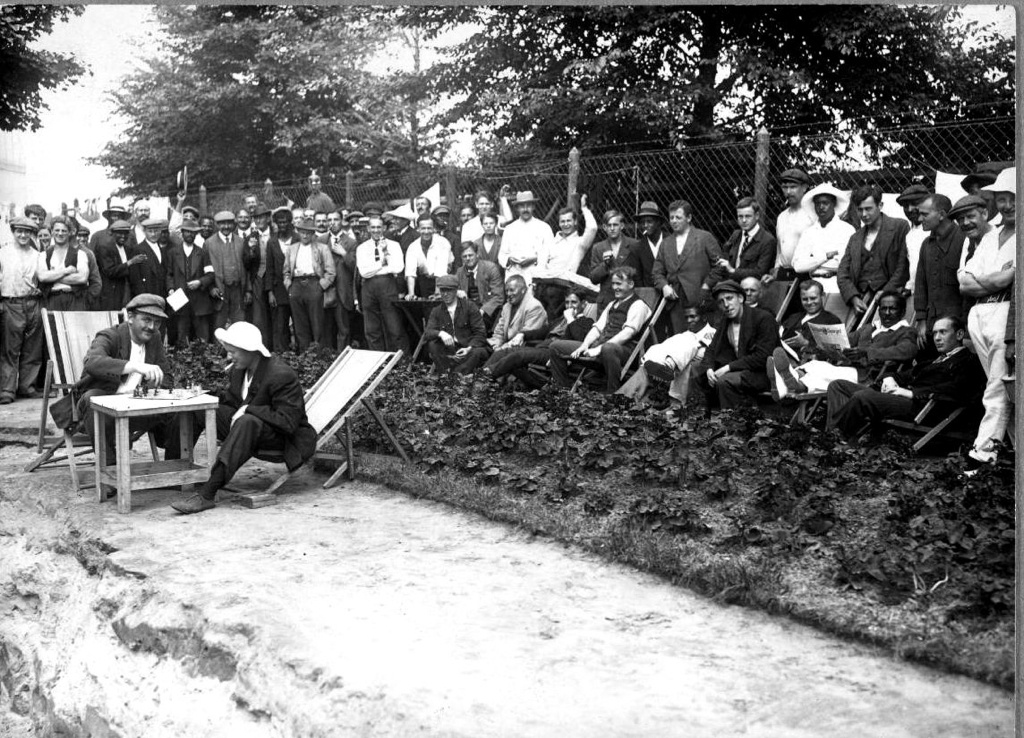

The small photographic exhibition Ruhleben 1914–1918 at SOAS’s Brunei Gallery at University of London gives unique insights into life there. Its marginal location reflects the actual marginality of the men’s situation a century ago.

Depicted are all sorts of BAME men — outnumbered by around 15 to one by other Britons — and Caribbean musicians posing in style, a shivering Sikh next to plump officers in Prussian helmets, Sierra Leonean ships’ firemen and smartly suited young men giving earnest accounts of themselves to a German anthropologist.

There were 5,500 detainees at peak, within what curator Sonia Grant calls a “Little Britain.” Effectively, it was an outpost of empire that replicated its social and racial strictures. They lived in racially segregated stables unfit for human habitation.

But sometimes mixing was more nuanced. Black musicians played in the orchestra, there was mingling at the canteen — the former grandstand — and cricket teams were mixed.

Thirty-year-old Samuel Davies, a Freetown fireman on the Oran, was one of the black seamen who received lessons in reading and writing, advertised in a replica poster on display, while enlarged official record cards poignantly separate workers.

And there are official group pictures telling an “it wasn’t so bad” story. But what can only be guessed at is the question of how whites treated blacks at Ruhleben at a time just prior to 1919 when white rioters were to attack black people in Britain's cities.

Fascinatingly, Grant’s book Ruhleben 1914-1918: African Diaspora and Arab Civilians Interned in Germany, to be published this summer, contains a Daily Herald front-page report by interned Jamaican teacher Sylvester Leon.

“We Ruhlebenites were able, from the very start, to keep in touch with the incidents of the [German] revolutionary movement,” he wrote. Excitement climaxed at the November 9, 1918 proclamation of a republic just 10 kilometres away in Berlin.

“The revolution is become a stark reality... it is in our midst,” he reported. And the Soldiers Council at the camp sent off detainees with a message of internationalist solidarity.

More interventionist captioning was required when I visited but a helpful handout for background is now available for this immensely important exhibition which reveals yet another hidden aspect of black and WWI history.

The exhibition is free and runs until March 23, opening times: soas.ac.uk/gallery.

The book Ruhleben 1914-1918: African Diaspora and Arab Civilians Interned in Germany will be published by Pen Stroke Publishing, penstrokepublishing.com.

Sonia Grant welcomes invitations from venues to host the exhibition and can be contacted at [email protected]