This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

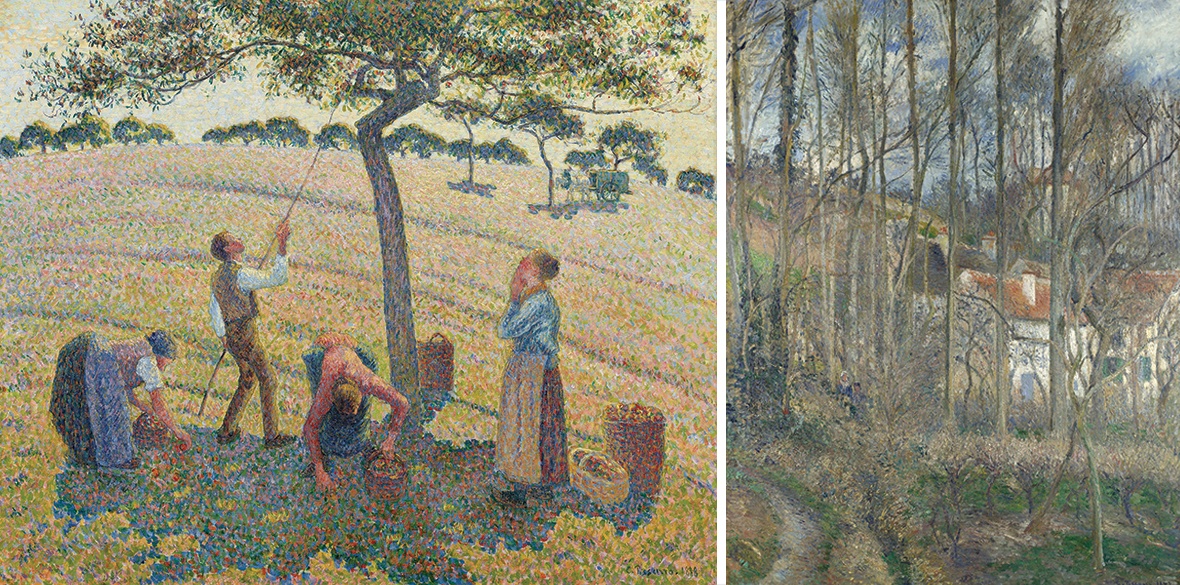

Pissarro: Father Of Impressionism

Ashmolean Museum Oxford

ACCORDING to the marketing bumf for the current exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, Camille Pissarro is the Father of Impressionism.

I first discovered his art when I was working in London. I loved the Impressionists and so made a trip to the Courtauld Institute where I came across his painting of Lordship Lane Station, Dulwich (1871). This made a big impression (ha!) as at the time I was renting a room in the same Lordship Lane, Dulwich.

What on Earth was an Impressionist doing in my neck of the woods? I couldn’t miss this latest chance to catch up with the old chap and find out the answer to my question.

In the art world impressionism is still a big draw and Pissarro played a key role in this movement. Indeed, the curators make the bold claim that without him “there would have been no impressionism.”

Pissarro (1830-1903) stuck to impressionism’s radical character all through his career, even while experimenting with different styles and techniques, more so than the other artists associated with the movement.

Though best known as a landscape painter his landscapes are always populated with people: his friends, growing family, domestic servants and farm workers, all inhabiting the fields and marketplaces of rural France.

Pissarro’s social vision was expressed in his art. As a committed anarchist his vision of society was one of small communities, bound by shared work. He had great respect for the rural labourers he lived among, drawing parallels between his work as an artist and theirs. He showed a strong interest in the dignity of their work and its co-operative nature.

Pissarro’s radicalism appears to stem from his childhood in Saint Thomas, then a Danish colony in the Caribbean. His family of Sephardic Jews had travelled there to look after a hardware store belonging to a deceased uncle.

He attended a Moravian school alongside Afro-Caribbean children, in an environment of racial and religious tolerance.

Having a talent for art he was packed off to study in Paris. France post-1789 was a very unstable place with a whole series of radical and even revolutionary upheavals. Pissarro read Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin and hoped that the tumult would lead to a radical transformation of society.

He developed his own radical views and often contributed to journals like La Revolte and Les Temps Nouveaux. In 1868 he managed to get one of his landscapes into the Paris Salon.

A couple of years later the Franco-Prussian war broke out. As a Danish citizen he left for London and went to live with family friends in Upper Norwood, explaining the nod to Dulwich.

It was in Croydon that he married his mother’s maid, Julie Vellay, with whom he had formed a relationship having already caused her to get the sack when she had their first child in 1863. She would go on to have seven children, creating an artistic dynasty as six of them went on to become painters.

His politics affected every aspect of his life and as the head of his own family he treated all members of the household as equals, all with communal responsibilities, yet always encouraging their artistic endeavours. There is an uxorious painting of Julie Pissarro, in the exhibition, entitled Sewing, the Red House Pontoise, (1877), and many of family members.

Although I fell in love with the pictures he produced in England, those of Sydenham, views of the Crystal Palace and of Dulwich College, the English of the time didn’t like them very much. So he went back to France as soon as he could only to find most of the work he had left behind had been destroyed in the conflict.

In 1873 he helped establish a collective society of 15 aspiring artists called the “Societe Anonyme des Artistes, Peintres, Sculpteurs et Graveurs.” This group included Cezanne, Monet, Manet, Renoir, Sisley and Degas and the following year they held their first “impressionists” exhibition, which we know shocked the critics, but caused a revolution in the world of art. Pissarro exhibited five of his works; the rest as they say is history.

Despite this newfound fame Pissarro was still something of an outsider. He returned to the countryside to continue his work; he believed that to defend anarchism in his art he had to be dedicated to the clear-sighted pursuit of the “sensation” or the impression.

In this period Pissarro frequently refers to his anarchist principles in his letters, occasionally contributing illustrations to anarchist publications, notably La Charrue (The Plough).

One incident that split France at this time, including the art world, was the Dreyfus Affair. Pissarro, Monet and their old friend and supporter Zola were Dreyfusards, as were a bunch of younger radical artists, Luse, Signac and Vallatron, friends of his son Lucien, who had encouraged Pisarro’s exploration of pointillism.

He wrote to Zola after the publication of “J’Accuse” congratulating him on his great courage and signing the letter, “Your Old Comrade.” Sadly, some of his oldest friends, including Degas and Renoir, shunned him as a result. Degas was very critical of Pissarro’s art and when reminded that he once thought very highly of him, he is reported to have replied: “Yes, that was before Dreyfus.”

What complicates this story somewhat is that in December 1889 Pissarro sent a series of drawings to his English nieces, Esther and Alice Isaacson, to educate them about modern capitalism. These were some 30 drawings bound in a book called the Turpitudes Sociale, essentially an artistic take on the social structure of late 19th-century France.

Its illustrations look like a list of all the social ills of French society from an anarchist perspective in that they are portrayed as coming from the city and the urban world of factories. There is a crude Marxism in these drawings, however the drawings that represent Capital, while being caricatures in the Monsieur Prudhomme style, are certainly anti-semitic.

He went on to describe one as: “The statue of the golden calf, the God of Capital. In a word it represents the divinity of the day in a portrait of Bischoffheim[sic], of an Oppenheim, of a Rothschild, of a Gould, whatever. It is without distinction vulgar and ugly.”

This is the paradox of Pissarro. On one hand he defended Dreyfus and was of Sephardic heritage, but he also used offensive stereotypes. Unfortunately, these types of caricatures were popular in anarchist literature of the 19th century, a handy shorthand for critiquing the capitalist class.

However, it’s hard, knowing what we know now, not to see how damaging and contradictory this kind of portrayal can be.

Pissarro died in 1903 never living to see Dreyfus being exonerated. Nevertheless, his legacy is immense. I think Zola was right when he described his work as “heroic simplicity.”

The Pissarro family archive found a home in the Ashmolean, it is the core of this exhibition. Get along if you can, you will not regret it.

Until June 12 2022. Box office: ashmolean.org