This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

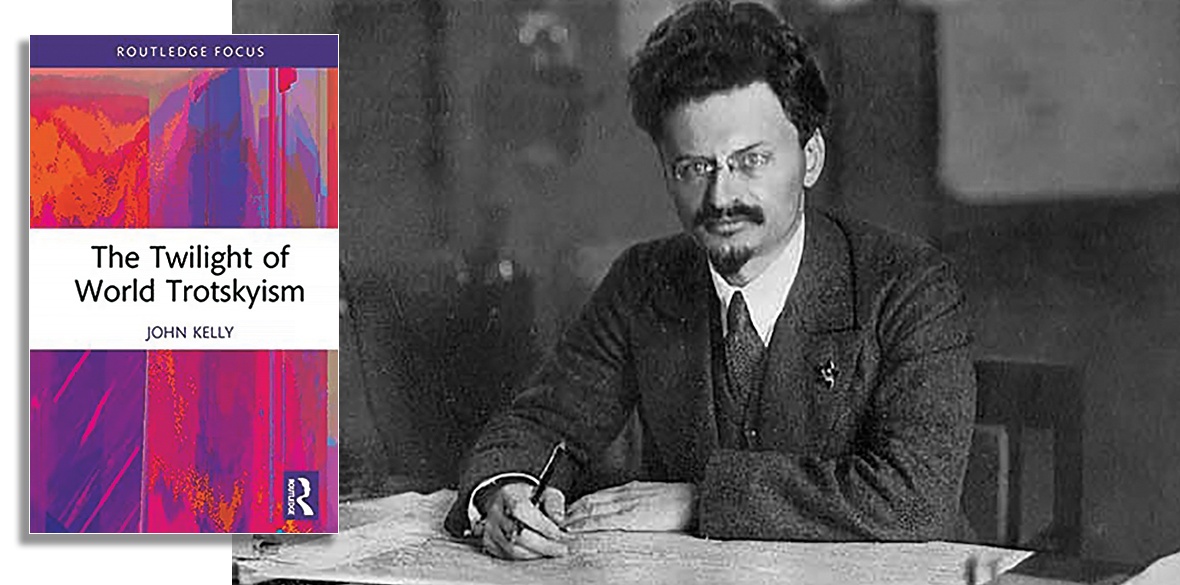

The Twilight of World Trotskyism

By John Kelly

(Routledge, £44.99)

JOHN KELLY’S new book on Trotskyism could not appear at a more opportune moment.

Faced with an economic and political system struggling to maintain its global hegemony, the left has rarely been offered such an opportunity to present an alternative.

However, since the Bolshevik Revolution, the left has been divided on how best to build a socialist alternative.

Trotskyism, as is well-known, grew out of the acrimonious split between Stalin and Trotsky and the latter’s eventual expulsion from the Soviet Union and murder by Stalin’s agents.

The various Trotskyist parties that emerged globally as a result never achieved the prominence hoped for.

Most of them remained minuscule and prone to splits. They have never, Kelly points out, managed to become mass parties or been able to effectively challenge capitalist power structures (with, perhaps Sri Lanka and Bolivia being short-term exceptions).

Their very raison d’etre seems to have been more characterised by an implacable opposition to “Stalinism” and to what they define as Stalinist parties, than to their avowed aim of achieving a socialist society.

This was demonstrated by the uncritical embrace by Trotskyist parties worldwide of the Polish Solidarnosc movement during the 1980s, because they saw it as “a workers’ movement to overthrow Stalinist bureaucracy,” not recognising that it was largely orchestrated by a reactionary Catholic church and conservative working-class elements.

The general portrayal of the Soviet Union as a state capitalist regime was also, in Marxist terms, a rather baffling description.

Trotskyist parties have also been characterised by an overpreponderance of young members, rather than reflecting the age range of the population at large.

And by a rapid turnover of this highly motivated young membership (mainly students) who form their core but who become quickly exhausted, disillusioned, and soon fall away. That is a serious weakness for any organisation.

Trotskyist parties are typified by an intractable opposition to so-called trade union bureaucracies, a reluctance to join broad fronts to oppose various measures or policies, but are more intent on building their own organisations; their aims are also based more on their own narrow perception of the world rather than the aspirations of the wider public.

Thus, favourite campaign slogans are, for instance, calling for a “general strike now” or “end capitalism,” which hardly resonate with those more concerned with achieving a wage rise, better housing or improved working conditions than in nebulous distant utopias.

As Kelly points out, their whole ideology is based on a largely unreconstructed Bolshevik world outlook, doctrinaire and intransigent, despite the changed circumstances since 1917.

The theory of “permanent revolution,” for instance, is one of the most distinctive leitmotifs of Trotskyist doctrine. The debate between Stalin’s concept of “socialism in one country” and Trotsky’s “permanent revolution” however, was, Kelly argues, polarised by both sides.

To begin with, Trotsky himself was a Menshevik and only later joined Lenin and his Bolshevik party.

While Trotsky presciently and early on criticised Lenin’s call for a centralised, disciplined party and that the party organisation would substitute itself for the party, the central committee substituting itself for the party organisation and finally a dictator substituting himself for the central committee. But, by the mid-1920s, Trotsky came to accept the Bolshevik monopoly of power.

“There were several trajectories offered after Lenin’s death and there were commonalities between pre- and post-Lenin Bolshevism: “there was a restriction of pluralism, an authoritarian, one-party state and the preparedness to use violence against political opponents, and it is clear that Trotsky wholeheartedly subscribed to all of them,” says Kelly.

Trotsky’s positive attributes are well-known: he was a gifted orator, a cultured and cosmopolitan intellectual, a stylish writer. He was repeatedly elected onto the central committee and in the early years of the revolution was entrusted with important offices of state and was the individual chiefly responsible for creating the Red Army.

Following Lenin’s death, Stalin was able to take control of the party apparatus because of his deviousness and networking ability.

Trotsky — the other obvious candidate — was viewed by many in the party as rather aloof, even arrogant, not a team player, and this, no doubt, facilitated Stalin’s rise to dictatorial power.

When the German Marxist, Karl Kautsky, criticised Lenin’s authoritarianism and the Bolshevik party’s monopoly of power, Lenin denounced him as a “renegade” and two years later Trotsky was equally scathing in his booklet Terrorism and Communism, a vitriolic attack on Kautsky.

Trotsky was also instrumental in suppressing the 1921 Kronstadt rebellion by brute force, but says almost nothing about this in his autobiography. It demonstrates that he was no vacillator when it came to using violence against opponents. This is worth bearing in mind when considering the heroic stature he acquired within the Trotskyist movement.

“Trotskyism and Stalinism cannot be reduced to a crude contraposition of a heroic Bolshevism and a Stalinist tyranny that have nothing in common,” Kelly writes.

The ideas of permanent revolution, disciplined vanguard parties, democratic centralism etc are contentious and problematic — what is the status of permanent revolution in the light of the many revolutions led by non-working-class forces that have overthrown autocracies?

Also contentious is Trotsky’s pejorative view of “bureauracy” as inefficient, self-serving and parasitic and arguing that the Stalinist “bureaucracy was a purely counter-revolutionary force, protecting the USSR by betraying revolutions in other countries.”

Kelly looks at the development and distribution of Trotskyist parties globally. “By 2022 there are now 32 ‘Fourth Internationals’,” he writes, “but it is their geographical concentration that is striking — 26 of these organisations are headquartered in just four countries, the US, Argentina, Britain and France. These countries have also contained most of the largest Trotskyist parties.”

In terms of numerical strength and mass appeal, no Trotskyist party has ever achieved the status of the post-war Communist parties in Italy or France, for instance, and most of the many Trotskyist parties numbered no more than a few hundred members at most, and have been incredibly fissiparous, splitting into new mini-parties at a surprising rate.

In Britain the Trotskyist movement is dated from the formation of the Balham Group in 1932, following expulsions from the Communist Party.

Several Trotskyist parties and groups emerged from this humble beginning, the significant ones being the Workers Revolutionary Party, Socialist Workers Party and the Militant Tendency.

Some were characterised by their “entryist” politics (following Trotsky’s advice to enter the leftist Independent Labour Party as a secret faction) and attempts to infiltrate the Labour Party.

While these entryist tactics have not been successful in the longer term, the Trotskyist movement in Britain can claim much credit for several successful campaigns, such as the Anti-Nazi League, Anti-Poll Tax movement and the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign.

Alex Callinicos declared in the 1980s: “The Labour Party is a dead end for socialists … It is time to look for an alternative.”

Kelly concludes by saying: “After more than 80 years of Trotskyist activity, with no revolutions, mass parties or election victories to its name, the same logic surely suggests that the Trotskyist movement has become a dead end for socialists.”

A valuable primer for anyone interested in the role played Trotskyism in the history of the left.