This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

RETIRED BBC journalist Tim Sayer and his wife Annemarie Norton, theatrical costume maker and former ballet dancer, live in a modest north London terrace.

Its exterior looks much like neighbouring houses but stepping inside is to be transported into a wondrous domain whose every surface is crammed with art.

Paintings, drawings, photographs, prints, sculptures, antiquities and tribal art by predominantly living British artists greet you from all walls, ceilings, both sides of doors, floors and the staircase. They’re even in the bathroom and toilet.

Small sculptures and ceramics top bookcases groaning with art volumes, also crammed on floor-to-ceiling shelves nearby.

Equally unusually, these art lovers have bequeathed their entire extensive collection of more than 700 art works and numerous books, along with their house, to The Hepworth Art Wakefield Gallery, which specialises in modern British art.

Sayer says that this donation was prompted by his socialist beliefs, which he has retained ever since his late teens.

Keen to share their art with as many people as possible, the couple periodically open their unique house to various groups, as they’ve done over the past 20 years. “It was when we realised that ours was a collection, rather than just a house full of pictures, that we began considering what would become of it,” Norton explains.

Driven by left-wing principles, they wanted their donation to be accessible for free to the maximum number of people. They chose the west Yorkshire gallery “because London already has everything and does not need more and, after looking around, we eliminated poncey Southerners,” says Sayer.

Despite having no prior personal connections with Yorkshire, they settled for the Wakefield gallery because it is doing a lot for the town, it is free and the local people are highly supportive of it.

They also admire its Labour council leader Peter Box for his firm belief in art’s power to improve people’s lives and for his council’s consistent support of the gallery, including having partly funded its beautiful modernist building by David Chipperfield.

Sayer is a true art enthusiast with no art background and at school his art master despaired of him. In 1964, when he was just 17, he spontaneously spent a whole 10 shillings (50 pence) in a junk shop in Richmond-upon-Thames on a portfolio of 183 etchings, engravings, dry-points, mezzotints and lithographs from the 17th to the 19th century before they were considered valuable.

He still always buys quickly, spontaneously following visceral responses to art which appeals to his head or heart. So the collection is eclectic and personal, ranging from representational to abstract art.

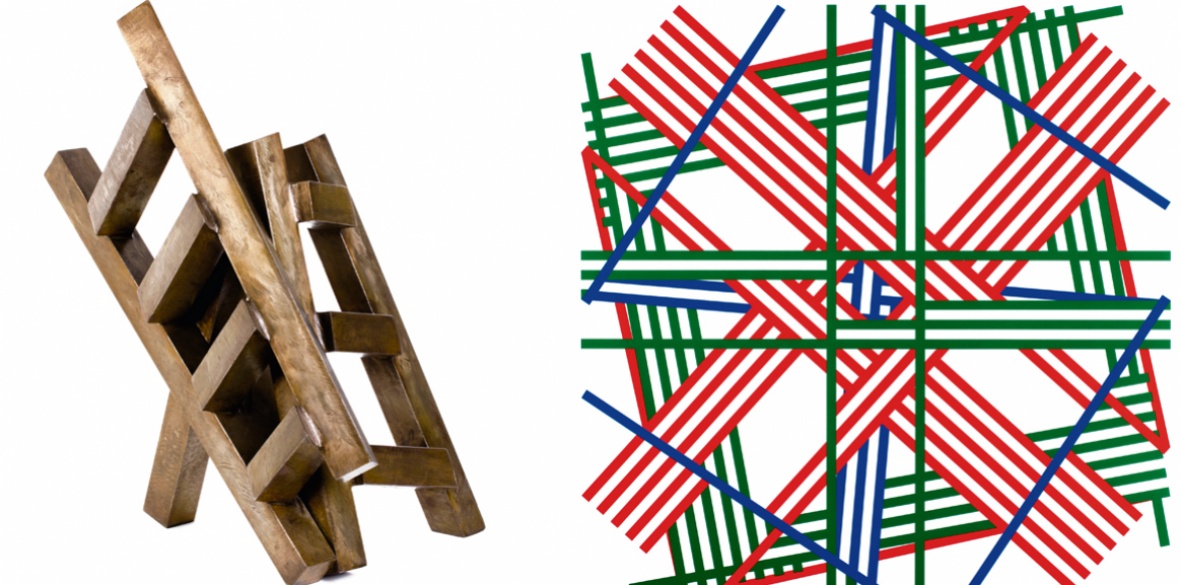

Some works are by well-known artists including Paul Nash, Roger Hilton, Lyonel Feininger, Bridget Riley, Henry Moore and Anthony Caro. But others are by total unknowns, including three drawings by Bethnal Green primary-school children.

But Sayer and Norton’s tastes have changed over the decades, veering increasingly towards abstraction of late. Their rare talent for hanging unlikely companions, differing in styles, subjects and mediums, create visual resonances, echoes or contrasts which delight, surprise and energise.

Sayer can afford these works because, he explains, he rejects the lavish middle-class lifestyle. Living modestly without children, car, holidays or television he soon found himself regularly spending half his BBC salary on his passion for art, so the collection grew over the decades.

He buys mostly from commercial art galleries, often in monthly instalments, or directly from artists and Norton has supported his buying habits for over three decades.

He takes his social role as art patron seriously, supporting struggling artists by paying studio rents, writing unpaid catalogue entries and giving references. Unlike many art buyers, he never purchases for financial speculation and only rarely sells works.

What motivates him as a collector is “a feeling of comfort and an acquisitive personality. I do not need therapy as the art itself is therapy.”

Apart from the tiny minority of artist superstars or those with private means, economic survival is a perennial problem for artists. The cultural famine caused by decades of neoliberal funding cuts by state and local government, along with acute cuts in the hitherto vital part-time teaching for practising artists, have seriously exacerbated the situation.

Sayer and Norton’s generous art patronage and donation to a free public gallery cannot rectify these problems. But they do help to mitigate their harshness until the arrival of a socialist government whose cultural policies will support artists and democratise public access to the arts.