This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

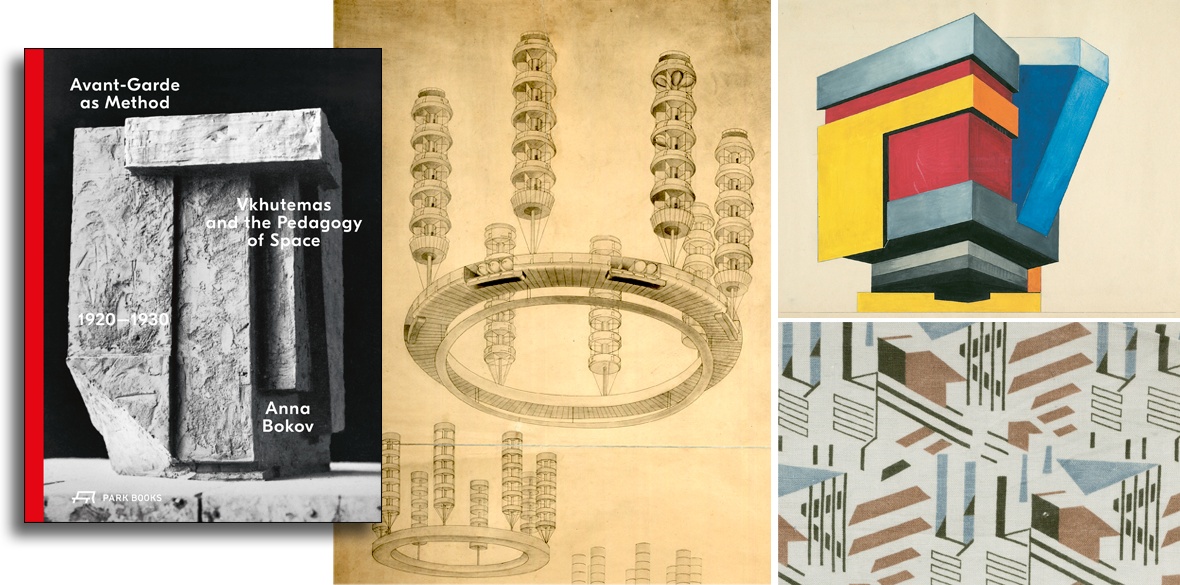

Avant-Garde as Method: Vkhutemas and the Pedagogy of Space 1920-1930

Edited by Anna Bokov

(Verlag Park Books, £35.45)

THIS magnificent book demonstrates how Vkhutemas’s dynamics, mission, personalities — and particularly its achievements in design, art and architecture — have stood the test of time, unlike any other educational project in modern history.

With an unprecedented wealth of detail, the book is an extraordinary work of scholarship from editor Ana Bokov.

In 1923 Lenin, in Our Revolution, posed the question: “What if the complete hopelessness of the situation, by stimulating the efforts of the workers and peasants tenfold, offered us the opportunity to create the fundamental requisites of civilisation in a different way from that of the west European countries?”

These were far from idle words. In 1920, by Lenin’s special decree, Vkhutemas had been founded to “give a unified artistic-theoretical and social-ideological foundation” and provide an “obligatory education in political literacy and the fundamentals of the communist worldview on all [its] courses.”

What Lenin proposed was a lock, stock and barrel realignment of all components in a revolutionary society with the human being at its centre.

In this staggering vision the visual arts, including architecture, would be used to research and teach empirical approaches to all aspects of revolutionary endeavour from housing to furniture, from industrial design to urbanism and from sculpture to painting or poster design and textiles.

It was a brave new world, to be defined by “objects, buildings and cities as a part-to-whole relationship,” and it was explored with inspiring energy and spectacular creativity.

The book owes much to its designers, Valeria Bonin and Diego Bontognali, who employ the Vkhutemas visual grammar to superb effect, offering volumes of little-known images of stupendous projects, sketches and models as well as photos of the lecture rooms and its students. Every page is a revelation.

Those who taught there constituted the Soviet Union’s arts avant garde, among them El Lissitzky, Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko, Kazimir Malevich, Lyubov Popova, Vassilyi Kandinsky, Varvara Stepanova, Naum Gabo, Gustav Klutsis and Konstantin Melnikov.

There were also support units, such as the famous architectural studio run by the three Vesnin brothers which had regular foreign visitors, among them Le Corbusier.

The school had 100 faculty members and 2,500 students. A compulsory introductory course consisted of learning the language of plastic forms and the influence of colour, in which art and science investigation were combined to teach, test and solve spatial composition.

The evolution of Constructivist, Suprematist and Rationalist orientations fed directly into the school programme, offering the experience of cutting-edge visual experimentation to all in this astonishingly versatile, multidisciplinary teaching and learning symbiosis that itself was called “conceptual works of art.”

The studio’s graduates were socialist, highly accomplished polymaths who could put their hands to virtually anything in the outside world.

Lenin visited Vkhutemas in February 1921 and engaged with students in an animated discussion about arts — views naturally contended but, when leaving, he said with characteristic self-deprecation: “Well, tastes differ, I am an old man.”

Yet, three years later, Vkhutemas’s own report on its activities warned ominously that the school was “[becoming] disconnected from the ideological and practical tasks of today.” Reforms to the curriculum followed, with a reduction of the art components and an enhanced orientation of graduates towards industry and design.

The international political climate had become intolerably hostile and the once lauded Vkhutemas was now isolated and seen as “communist,” hence to be repudiated.

But, in a Brutus-like blow to Lenin’s vision, it was the state itself under Stalin that had it shut down in 1930.