This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Alice Neel, “Hot off the Griddle”

Barbican Art Gallery, London

A NATURAL rebel, Alice Neel (1900-84) was born in Colwlyn, a staid Pennsylvania town which she said was “utterly beautiful in spring, but there was no-one to paint it.”

She wanted to be an artist from childhood but she had a placid, provincial upbringing in which her mother said: “I don’t know what you expect to do in the world, Alice. You’re only a girl.”

And as her family were not well-off, Neel became a secretary. But she insisted on studying art at night school and saved up to study at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women when she was 21 years old.

Like many a vivacious, good-looking young woman in the days when contraception was not easy to find, she was soon seduced, married and pregnant.

The death of her first baby aged one, followed by her bourgeois-bohemian husband taking their second daughter Isabetta back to his native Cuba, triggered Neel’s nervous breakdown in 1931.

Her next major lover, jealous of her commitment to painting, burnt over 50 canvases and 300 drawings.

Despite her traumas, Neel stubbornly continued to paint, later saying: “The minute I sat in front of a canvas I was happy, because it was a world, and I could do what I liked in it.”

Her early works expressed her personal pain and her sexual experiences in an emotive style.

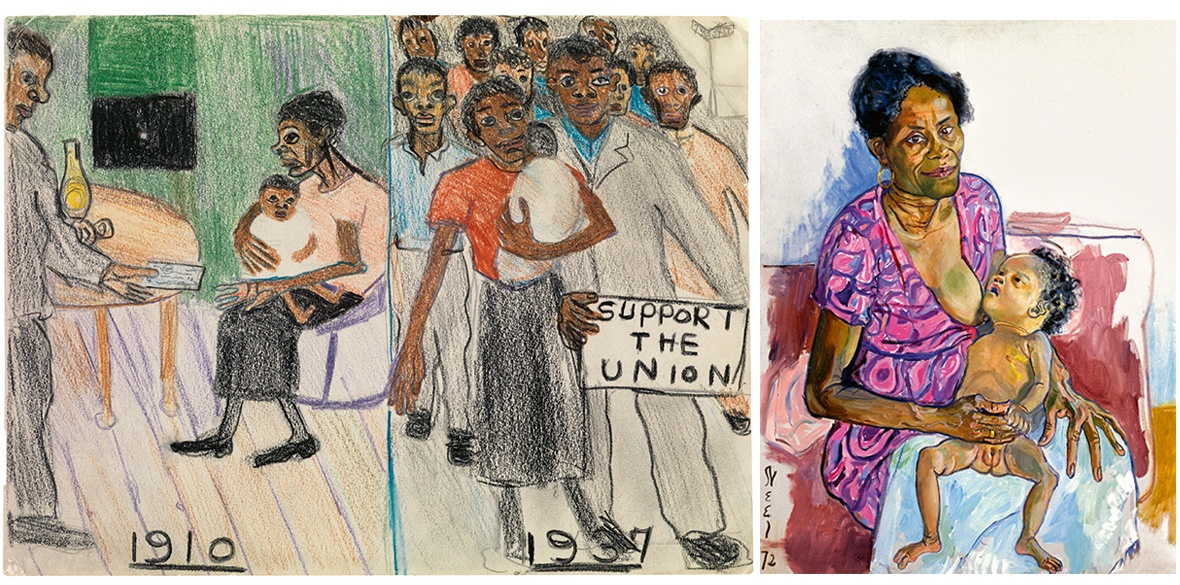

But in 1933, profoundly moved by the miseries of the Great Depression, she began her “revolutionary paintings”: angry exposures of social injustice and urban deprivation.

She soon became politicised and joined the Communist Party in 1935, remaining politically active throughout the dangerous McCarthy era and beyond, joining protests and demonstrations, although she admitted that she found party meetings too bureaucratic.

Nazis Murder Jews of 1936 depicts a big demonstration fronted by a worker holding a placard with these words written on it, and Communist Party banners behind.

Alongside such scenes of social engagement she initially discovered her creative destiny through non-commissioned portraits of left-wing activists such Pat Whalen, of 1935.

Seated at a table, shoulders high and both fists clenched over a copy of the American Daily Worker, the party organiser stares with sorrow and determination towards a better future.

![Pat Whelan, 1936 [Courtesy of the Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner]](https://morningstaronline.co.uk/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/NEEL.jpg?itok=zqMPAsUM)

Having moved to New York’s Spanish Harlem in 1938, she asked neighbours and acquaintances to sit for her, including The Spanish Family of 1943 in which a tired, anxious mother holds her baby on her lap with her two children at her sides, the frontal composition and narrow spatial recession adding to the painting’s unsettling message.

Portraiture remained Neel’s main subject matter throughout the rest of her life.

Almost always non-commissioned, these are paintings of people rather than portraits in the conventional meaning of the term.

Never one to idealise her sitters, Neel summed them up with brutal honesty tempered by her inborn empathy and socialist humanism. She loved to talk and she would discuss life with them as she worked, so capturing her sitters’ essential characters.

Avoiding pretentious compositions or poses she seated them either in a comfortable upholstered armchair or on an upright, rush-seated one, allowing them to adopt their natural postures which revealed as much about them as did their clothes and mobile facial expressions.

Although Neel rebelled against the restrictions of her traditional art education, its basis in drawing from life stood her in good stead, and she later said: “Drawing is the discipline of art.”

Despite using bold, unmixed colour, it is the confident, fluid and visible outlines of her figures which most define their forms.

We can sense the anatomical frame within their bodies, and we can see the acute observation of the individuality of their faces, hands and sometimes feet which tell us much about their personalities.

An admirer of Honore de Balzac, her portraits typify the changing ethos of the many decades through which she was active.

Neel was a brave, free spirit who eschewed both the dominant avant-garde aesthetic of Abstraction and the sweetened figurative art exemplified by Norman Rockwell.

A natural psychologist, she summed up her sitters’ psychology and characters with deceptively fluid ease.

![Courtesy estate of Alice Neel]](https://morningstaronline.co.uk/sites/default/files/styles/inline/public/AN%20in-txt%20webpic.%20Geoffrey%20Hendricks%20and%20Brian%2C%201978_0.jpg?itok=w26hbqr1)

Living on meagre welfare funds as an unmarried mother single-handedly bringing up two children, she doggedly persevered with her painting despite social opprobrium, few sales and limited critical attention until the 1970s when feminist art historians led by Linda Nochlin promoted her work.

Curated in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Barbican Gallery’s extensive display of medium-sized works on two floors suits the intimacy of its many bays.

Two quibbles — the London exhibition would have done better to use the Paris exhibition’s more descriptive title Alice Neel: Un Regard Engagé (a Penetrating Gaze) rather than its obscure title Hot Off the Griddle.

Secondly, a wall text incorrectly refers to Neel’s 1981 Moscow exhibition as being by the “first living artist to have a retrospective in the Soviet Union,” whereas many artists including Yuri Petrov-Vodkin, Alexander Deyneka, Pablo Picasso and Fernand Leger had exhibited there from the 1930s onwards.

Indeed Neel’s work was closer in content to Soviet Socialist Realism which she would have been aware of through American left-wing debates and publications.

Nevertheless the Barbican Gallery has done this superb artist proud.

Christine Lindey will speak about her book Art for All: British Socially Committed Art from the 1930s to the Cold War at the Financial Times Oxford Literary Festival on March 30 2023.