This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Paula Rego

Tate Britain, London

FIGURATIVE art has become fashionable again, apparently.

Yet the extraordinary Paula Rego probably couldn’t care less. Pushing on through the fashionable Young British Artists era of the 1980s, she has always drawn and painted what she needed to.

Born in Portugal in 1935, she was brought to England by parents opposed to the fascist Salazar regime — God, Homeland and Family was one of its guiding slogans and the Female Portuguese Youth was set up to train girls for domesticity.

And so Rego’s exiled youth in Britain was lived with this knowledge while developing her art at the Royal College of Art in the 1950s. There, showing hints of the future, she painted abstracts with echoes of Francis Bacon and Pablo Picasso.

It was more common for artists to go from figurative to abstract painting at that time but Rego’s journey was the other way around and by the 1980s she was producing extraordinary figurative canvases.

Many, challenging the suppression of women in her homeland and elsewhere, are about the fascist mentality. This is great narrative art, whose subject matter is the defiance of women from within their own nature and sources of vitality.

Look at the knowing expression on the girl’s face as she polishes her father’s boot in The Policeman’s Daughter (1987). It is as if the organic and life-affirming win out every time against the rigid and morally sterile.

The caption to Fantasy and Rebellion reads: “It was very important to go to the origin of the imaginative anger that provide the images of what we have inside us, without knowing what it is.” Yet Rego knew what much of it was — illegal abortions, marital rape, women trussed up like prize chickens to grace the bedroom and to reproduce. Women in fascist regimes.

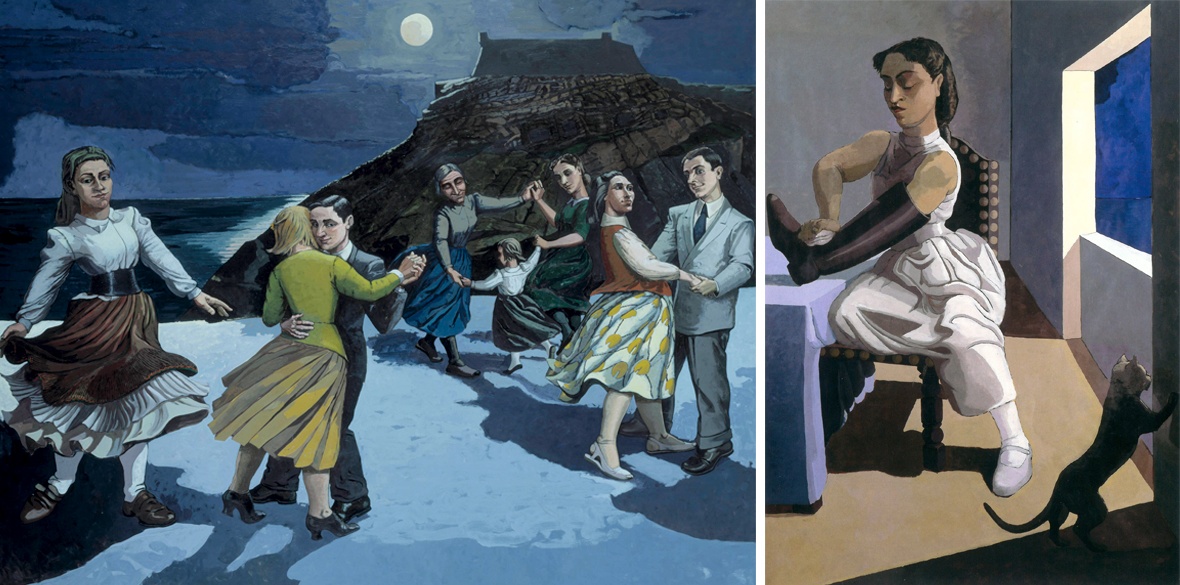

The famous epic The Dance takes up a whole wall but don’t ignore the drawings in the cases in the middle of the room. Sketches for it have a different sort of energy. Even before entering the exhibition Rego’s writing on the wall declares: “Good drawings are more intensely alive than any other art — they are about being alive.”

Rego paints not from resistance but confrontation and sometimes a thrusting joy and part surrealist, part expressionist, she defies whatever categorisation. Faces and bodies, painted in distortion, are truer and much of the work — assumed to be painting — is in fact done in pastel yet an epic quality endures.

The influence of well-known children’s stories is there in the amazing forms and delicious drawing of Snow White. This is narrative art of the highest order in which it’s always vitality that wins, life emerging from the dark side.

And for all the seeming effortless of her painting, we know that her life has been a struggle. Possession is a series of seven paintings of the same woman in different positions on the therapist’s couch — Rego’s actual therapist’s couch.

They represent a woman’s experience not just of emotional pain and healing but of martyrdom and self-determination. Instead of male possession of women, this is about depression and hysteria, the “diagnosis du jour” for many women in the 20th century. An immersive experience.

In 1990, Rego was the first artist in residence at the National Gallery. Turning it down initially, she then used the position to subvert many male artists like Velazquez or Hogarth, as in her majestic triptych Marriage a la Mode. Stories of Women contains the Dog Woman series, in which in some canvases bits of frivolous lace are draped incongruously against muscle and satin corsets strain to contain flesh.

The theme of the series Coercion of Defiance is abortion and its aftermath, with the canvases having the majesty of much Renaissance Catholic art in their suffering flesh but without the eye-rolls and upturned gazes of resignation.

Theatre of Life contains paintings of the early 2000s and what she calls her “dollies,” stuffed creatures that she has made and incorporated into her painting. In War, about the 2003 invasion of Iraq, one of them represents a terrified child in her mother’s arms.

This disturbing and visceral painting is equal to anything by Goya. Were any of the establishment that supported that war at the private view, I wondered?

The Pain of Others, a kind of coda, leaves us with the world as it is now and how it affects children and women. Here are refugees, trafficking and female genital mutilation: shocking but not depressing and a spur to action in the way that Picasso’s Guernica was.

Terrific, as is the whole of this important exhibition.

Runs until October 24, box office: tate.org.uk