This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Faith Ringgold

Serpentine Gallery, London

★★★★★

A VETERAN of the 1960s civil rights, feminist and Black Power movements, Faith Ringgold is a rare artist; she has much to say, all of it important and she expresses it in visually striking ways.

She was born in 1930 in Harlem where her fashion designer/maker mother and lorry driver father prioritised a college education and encouraged her love of art. Although her thorough but traditional art education never mentioned black artists, she’d grown up immersed in the culturally vibrant Harlem Renaissance.

The major African-American painter Jacob Lawrence lived in her neighbourhood and visited her parents’ home as did Duke Ellington and other artists, and she delighted in the vivid spectacle of the weekly Sunday parades of live choirs, musicians and people in their best finery.

Incredibly prolific since graduating in 1959, Ringgold has produced paintings, posters, story quilts, wall hangings, sculptures and children’s books and her autobiography alongside being an influential art educator and important political activist.

She recalls being inspired and politicised by reading “everything James Baldwin had written about the relationship between black and white America” and by Malcom X: “talking about us loving our black selves.”

Her weekly visits to view Picasso’s Guernica — then still in New York’s Museum of Modern Art — were also a key influence. Her acute awareness of the radically changing 1960s political climate spurred her need “to express the moment I knew was history.”

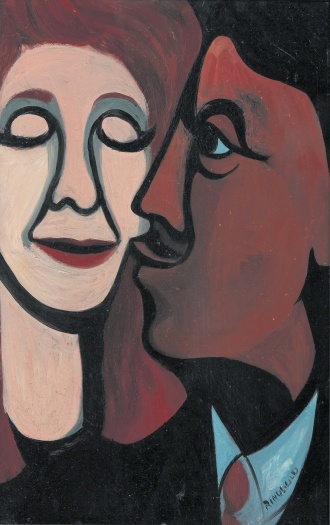

Her American People Series (1963-7) exposed America’s racial dichotomy. The small paintings condemn racist injustice — The American Dream depicts a hard-faced, arrogant white woman showing off her wealth, another shows a repressed, sad, black youth. But others offer hope by shockingly bucking racial and sexual stereotypes — a happy mixed race couple kiss, a black male artist has a white female model.

US Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power, of 1967, is one of three large paintings which completed the series. It greets visitors to the Serpentine Gallery. A grid encases one hundred deadpan faces inside the format of a US commemorative stamp. Ten black faces form a diagonal across 90 white ones, so conveying the US racial percentage at the time. Giddy black letters spelling out Black Power, tumble diagonally across the line of black faces, so forming an angry X across the white faces.

Henceforth Ringgold often added such layered meanings by combining images with texts which gradually reveal their meanings in similarly encoded ways. As in her 1970s political posters like America Free Angela in support of the jailed Communist Angela Davis.

In Woman Free Yourself the complex visual puzzles formed by the entangled letters’ diverse shapes create satisfying abstract compositions, while also acting as visual metaphors for women’s need to disentangle themselves from the social norms which entrap them.

In the 1970s Ringgold liberated herself from the male-dominated aesthetic which viewed large, stretched canvases as a mark of importance. These are expensive to make, awkward to move and store and require massive studios. Having discovered the beauty of Tibetan Tankas — brocade encased painted silk wall hangings — she began working with textiles. Combining painted imagery with appliqué, braiding, stitching, embroidering and quilting, she found her true medium, while also re-evaluating these disparaged, traditional women’s needlecraft skills.

The Slave Rape Series are stunning celebrations of the spirited resilience, resistance and resourcefulness of female slaves escaping sexually violent “masters.”

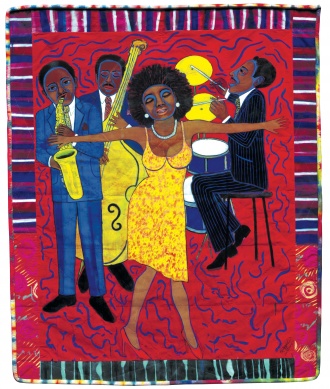

Large “story quilts” tear into US racial stereotyping, while others recall the magic of her Harlem childhood and celebrate Black culture as in the jubilant colours which depict the confident and talented musicians in Jazz Stories: Mama Can Sing, Papa Can Blow No 1: Somebody stole My Broken Heart of 2004.

More recently Ringgold created beautiful, political Tankas portraying inspiring pioneers of Black liberation with extracts from their key statements. My favourite being Sojourner Truth with her 1851 text Ain’t I A Woman?

When explaining her works Ringgold traces their roots to specific events or ideas. Its topicality is vital, but like all great topical art, the urgency and sincerity with which the messages are expressed gives it universality.

In the sixties Ringgold was accused of producing “political,” “protest” or “socialist realist” art when this was disparaged by the dominant aesthetic which championed non-emotive art, especially abstract Minimalism, and also ignored the Harlem art scene.

Yet going against the against the grain is precisely what makes Ringgold’s art so special, because it is driven by an urgent sense of social responsibility rather than by a desire for professional success. And rather than creating worthy, but turgid exposures of injustice, she mingles condemnations with inspiring calls for change and optimistic portrayals of past African-American achievements. And her art inspires by being a joy to look at as well as being thought provoking. This free exhibition is a real treat.

Ends Sep 8 2019. Free. www.serpentinegalleries.org