This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

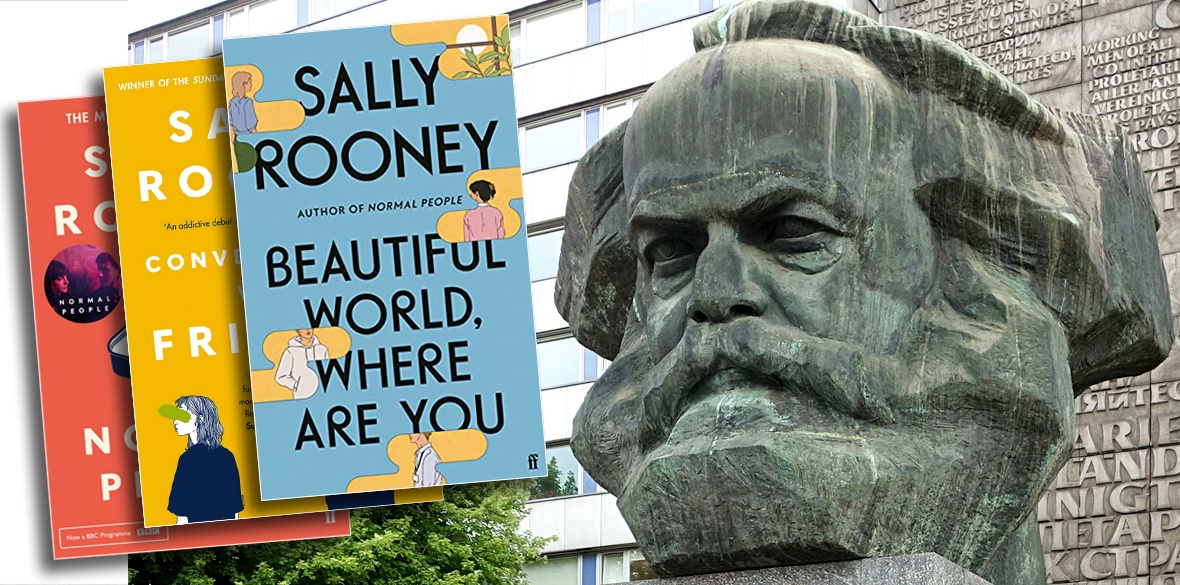

RECENTLY, 30-year-old Irish author Sally Rooney was in the headlines following her refusal to grant the translation rights of her new novel Beautiful World, Where Are You (2021) to the Israeli Modan publishing house. Since then 70 prominent authors backed her decision in a joint statement.

Two bookstore chains with branches in both Israel and in the occupied territories responded to Rooney’s decision by removing her novels from their stock.

So who is Sally Rooney and what are her books about?

Rooney was born in 1991 in Castlebar, in the west of Ireland, and describes herself as a Marxist. She studied English at Trinity College. “I don’t know what it means to write a Marxist novel. I don’t know and I would love to know. It is the analytical structure that helps me make sense of the world around me,” she said in an interview.

Her first novel, Conversations with Friends (2017), focuses on two young women, Frances and Bobbi, who, having met at school, are now studying in Dublin. The novel is primarily about sexual relationships among young people, about the question of true love and genuine friendship in an environment where none of this seems to be possible.

Most unusually for a contemporary novel, both protagonists see themselves as politically left wing, even communist: “My mother was a kind of social democrat, and at this time I believe Bobbi identified herself as a communitarian anarchist. When my mother visited Dublin, they took mutual enjoyment in having minor arguments about the Spanish Civil War.”

Frances, the narrator, comes from a single-parent working-class household. She is the only character in the novel’s plot who is not wealthy, the only one who has no money.

Despite recurring references to left-wing views these, however, do not directly inform the novel’s plot, which revolves mainly around sexual relationships.

Alienated relationships prevail. No help is given to them, nor are there any alternatives offered by Rooney.

In her second novel, Normal People (2018), Rooney focuses again on young people, Marianne and Connell, and their relationships in their final year at school and later at Trinity College Dublin. Once more, one of the two is working class with a single mother, while the other comes from a dysfunctional wealthy family.

In both novels, the working-class child’s mother is the one older character that is better developed — although drawing people over 30 is not Rooney’s forte.

The plot is a little more complex than in the first novel. Again, it is striking how left wing the main characters think to the extent that recommending the reading the Communist Manifesto seems perfectly normal. Connell’s mother is also left wing.

Class distinctions are even more clearly highlighted in Normal People, and it’s emphasised that Trinity continues to be the elite university of the bourgeoisie. The larger social themes of class struggle and political protest are echoed in the conflictual relationships between the characters: “They went to a protest against the war in Gaza the other week with Connell and Niall. There were thousands of people there, carrying signs and megaphones and banners.”

Rooney is also keen to highlight the class nature of the culture industry. Connell goes to a literature reading at the university: “Literature, in the way it appeared at these public readings, had no potential as a form of resistance to anything.”

This quest for alternatives to the capitalist culture industry takes up even more space in Rooney’s latest novel, Beautiful World, Where Are You, titled after a Friedrich Schiller poem.

Questions of interest to the author are discussed primarily in an email correspondence running through the book between Alice, the young, successful author and her friend Eileen.

The discussion covers a whole spectrum of political and philosophical-historical issues from a left-wing perspective. Alice’s comment on contemporary Euro-American novel is succinct: “It relies for its structural integrity on suppressing the lived realities of most human beings on Earth. To confront the poverty and misery in which millions of people are forced to live, to put the fact of that poverty, that misery, side by side with the lives of the ‘main characters’ of a novel, would be deemed either tasteless or simply artistically unsuccessful.”

While the end of the first two novels gives vague hope, the third ends surprisingly. Rooney does not write escapist literature, but the kind that confronts alienation by depicting alienated relationships. Her novels have struck a chord with many people worldwide because her readers recognise their own sense of isolation.

She understands that literature written from a Marxist perspective needs to go deeper than having characters make progressive political statements. The depth of political meanings must also be skilfully expressed in the plots and the actions of her characters, as in novels like The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists.