This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IN THE popular imagination, the German Democratic Republic is indelibly linked with ideas of authoritarianism, poverty, secret police, stuffy bureaucracy and a generalised absence of democracy.

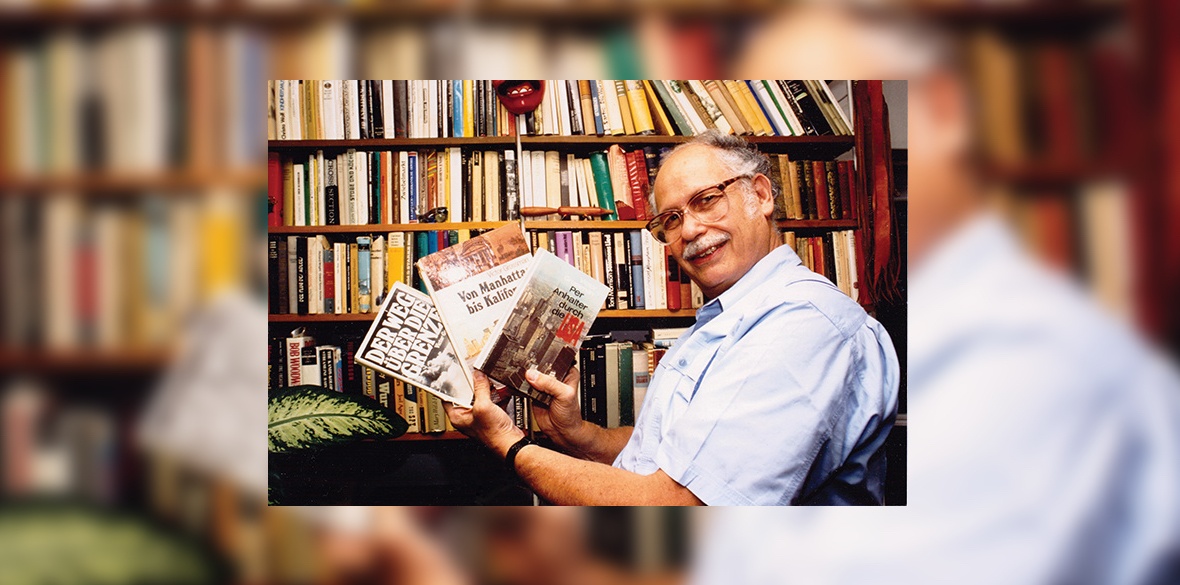

Victor Grossman is uniquely well placed to challenge this McCarthyite narrative. Born in New York in 1928, he joined the Communist Party while studying at Harvard in the late 1940s. Drafted into the army, he defected to the GDR while stationed in Austria.

Marrying a German woman, studying and working, raising children and grandchildren, he lived in East Germany until its 1990 absorption into the Federal German Republic (FRG). He still lives in Germany today.

A Socialist Defector is thus able to offer a nuanced and realistic account of life in the GDR. Although Grossman doesn’t shy away from criticising the assorted failings, mistakes and excesses of the East German socialist experiment, his account is very different from the standard cold-war nonsense.

Comparing his experiences of German socialism with his experiences living in the capitalist world, he finds that the socialist model was superior in several important ways.

Although the GDR was certainly poorer than the US or the FRG, it emphasised social justice and equality. Exotic foodstuffs and attractive consumer goods were often difficult to come by but nobody went hungry. Everybody had a roof over their head and rent — typically between 5 to 10 per cent of income — was always at an affordable level. Evictions were prohibited by law and homelessness non-existent.

Education was free at every level, from kindergarten to university. Much like in Cuba today, Western sanctions meant a shortage of some medicine but the healthcare system was comprehensive, free, and of excellent quality. A 10 percent social insurance contribution bought you access to “a full protective umbrella.”

Even in modern Britain, with our magnificent NHS, it’s difficult to imagine the sense of freedom and security that come with a comprehensive welfare state and guaranteed full employment.

There was no organised crime scene, no drug addiction and no prostitution. Women had full economic and legal equality in the GDR long before they did in West Germany. In 1968, the old German law against homosexuals, already ignored, was annulled. It wasn’t until 1994 that the FRG caught up.

While the West German state was packed with former nazis, the GDR was from the start an unambiguously anti-fascist state. The leading politicians had fought against fascism in Spain and Germany. Former nazis were removed from positions of influence and new teachers, lawyers and judges were trained from among the ranks of the working class, with a clear anti-fascist ethic.

This was combined with a profound internationalism. The GDR gave practical, financial and moral support to the freedom fighters of South Africa, Namibia, Mozambique, Angola and Vietnam, crucial support to Cuba and Nicaragua and stood in solidarity with the Allende government in Chile. “All this time,” Grossman writes, “rulers in Washington and Bonn supported every fascistic dictator from Haiti or Guatemala to Chile.”

Grossman notes the generation gap that developed between the leadership and those who hadn’t directly experienced the war or the anti-fascist struggle and he criticises the leadership for its excessive caution and secrecy, which led to dissatisfaction and disengagement.

As such, the book offers some valuable insights into why the GDR wasn’t in the final analysis able to withstand the extraordinary pressure it faced as a socialist state in an imperialist world.

While mourning the loss of so much of the socialist world, the book is ultimately a story of hope, encouraging us to learn from the successes and failures of German socialism in the 20th century and to take these forward in the struggle for a better world in this.

Grossman takes heart from a renewed radicalism among young people, highlighting the Black Lives Matter movement, Occupy Wall Street, the Oxi fight in Greece and the resurgent Labour left under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn.

He ends by urging us to unite our struggles and fight as one against a merciless, militaristic, neoliberal capitalism.

Hugely interesting, this accessible and endearing political memoir deserves to be widely read. Those looking to explore the GDR’s history further are also recommended to read Stasi State or Socialist Paradise?: The German Democratic Republic and What Became of It by Bruni de la Motte and John Green.

Published by Monthly Review Press, price £17.99.