This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

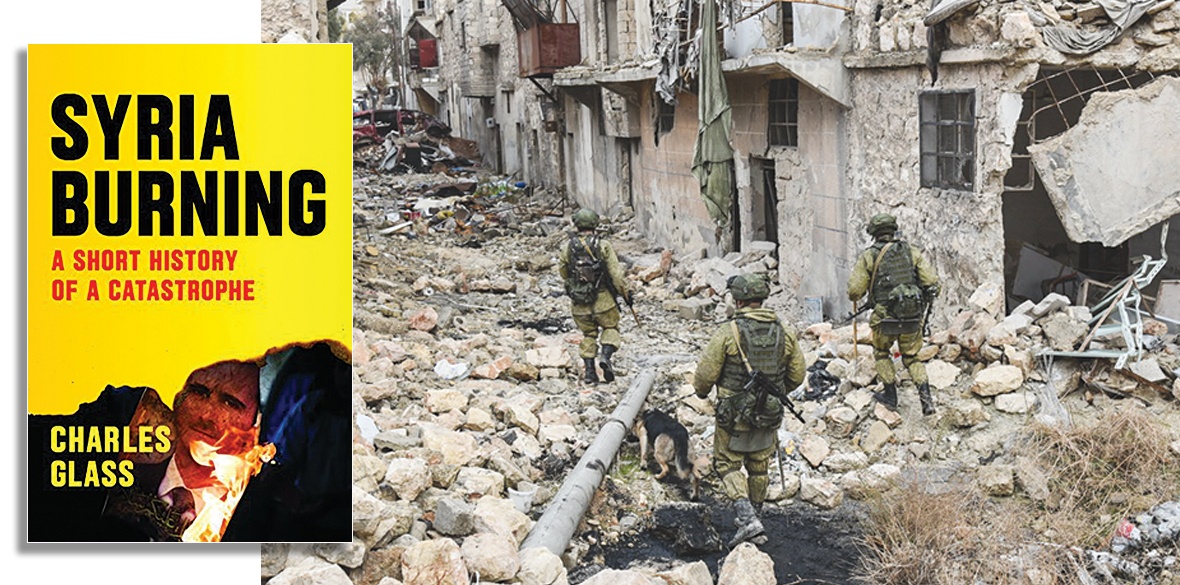

Syria Burning

by Charles Glass, Verso, £8.99

THIS reprint of Charles Glass’s 2015 book Syria Burning holds up well eight years on, as the war recedes but the country remains irretrievably broken.

The veteran journalist delves into Syria’s history, assisted by his extensive travels and interviews with Syrians, to help explain the catastrophe that befell the country.

It was already clear when the book was published eight years ago that the early hopes of protesters for a transition to democracy, an end to torture and more freedom had evolved into a brutal civil war pitting Bashar al-Assad’s fearsome intelligence services and military against foreign-funded militants who were waging a sectarian crusade against Syria’s mosaic of religious minorities.

In the middle were the aspirations of young Syrians for a better future that were crushed in a vicious pincer, with tens of thousands swept up at checkpoints and disappeared into Assad’s cruel prison network. If they survived this, Islamic State and al-Nusra front might pick them off for opposing the Arab Gulf and Turkish-backed groups’ vision of a strict Sunni caliphate in a country that had been a secular state for generations.

The concept of the “proxy war” is something of a cliche and often hides the real class conflicts and political motivations of domestic actors, which foreign powers then pile into in pursuit of their own agendas.

Glass provides useful insights into how a government that provided world-class healthcare and education for all could also act like a military colonial power fighting an insurgency with all the weapons at its disposal.

It was French colonial authorities facing a mass insurrection in 1925, with elite Sunni officers refusing to fight their countrymen, that soldiers from the marginalised Alawite minority were given the role of suppressing the revolt.

Later in 1949, a US-backed military coup against Syria’s first democratic government helped destroy any prospect for stable civilian rule following independence from France.

Again, the Alawite officers emerged as the victors in the series of coups that occurred in the 1950s and ’60s, with the Assad family seizing the throne in 1970. The fear that the old Sunni elites would turn on the new rulers ensured the Assad’s maximalist approach to security.

The regime faced violent Islamist opponents in 1979-82 and again 40 years later, but treated civilian protesters with even more brutality.

Referring to Lebanon’s brutal civil war that preceded Syria’s, Glass describes how aspirations for an egalitarian democratic society by Palestinian militants in 1975 were eclipsed in a war in which every foreign power had a stake, and only the most ruthless prospered. This too is Syria’s tragedy.

Last year I spoke to Syrian architect and writer Marwa al-Sabouni about life in her home city of Homs.

She said the city had been reduced to less than half its size with whole areas still pancaked by the fighting, with little or no reconstruction. Just as the war ended, the US imposed sanctions, then Covid happened, then the Ukrainian war, and finally the February earthquake.

“It’s a country that is suffering in silence now. It’s worse than the days of conflict, but nobody’s paying attention,” Sabouni said.

“We have nothing left, literally. We don’t have electricity, we don’t have infrastructure, we don’t have cooking gas, we don’t have fuel.” At Eid people would queue at petrol stations from dawn to night, sleeping in their cars. “This is how they were spending their holidays. It’s painful, heartbreaking.”