This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THERE is a long poem in Alan Morrison’s fantastic new collection Shabbigentile (Culture Matters, £9) about the 1930s Left Book Club, invoking the idea of “red belles-lettres ringing red bells/Of rebellion”:

“Now once more books need to be mobilised/Against the oncoming monsoon of moral/Panic and scapegoating in the face of a new/Gentrified fascism, a bespoke chauvinism ... Poisoning the well of tolerant discourse.”

In many ways the whole collection is about mobilising books as “print-antidotes/To right-wing hegemonies.” And in a book thick with references to Jack London, Charles Dickens, Gyorgy Lukacs, Henri de Saint-Simon and John Davidson, Morrison knows that the best books are on our side.

As always, his poetry is dense, eloquent and rich with information, ideas and arguments. There are some important long poems here, notably Another Five Giants, about Tory and New Labour attacks on the welfare state, Not Paternoster Square, on the Occupy movement and St Jude and the Welfare Jew, which tackles racist tabloid newspapers accusing Jeremy Corbyn of anti-semitism.

The title of the book is a play on “shabby genteel” and an attack on the ways that a nominally Christian society like Britain contains the forces of neoliberalism, austerity, racism and fascism within it:

“red-top parrots of blue torch opinions/Igniting blue-touch tabloids, cropped topics,/Pre-packaged antagonisms, analgesic/Propagandas, austerity narratives... rabid Malthusians and poison pen Mendelists.”

The Storm Called Progress (Shoestring Press, £10) by Edward Mackinnon is a kind of verse autobiography in which moments in the author’s early life are remembered via public events— the execution of the Rosenbergs, the arrest of George Blake, the Profumo Affair, perestroika, the dismemberment of Yugoslavia, the Gulf war, Gaza, Syria: “I have watched the wars being re-run nightly ... the old’s dying, the new can’t be born.”

There are some fine individual poems here such as Excuse Me, But You Can’t Write Poetry About This, Questions, Snapshots of Empire and The Faithful, about those who are “unwilling to acknowledge/that the world has changed, and quite possibly/for good... Their words are blown back in their faces/or are buried in the sand./Yet they refuse to turn./They are incorrigible./They stand in the wind.”

Keith Hutson’s debut collection Baldwin’s Catholic Geese (Bloodaxe, £12) is a hugely entertaining celebration of British musical hall and variety artists, the lost world of “acrobats and mimics, comics,/rope-dancers and whistlers... Black-face minstrels, ladder-climbers,/dentalists and paper-tearers.”

Many of the characters celebrated, like Hylda Baker, Frankie Howerd, Little Tich, Ivy Benson and Jimmy Clitheroe, are still well-known by some today. But Hutson is also interested in lost, exotic acts like Willy Netta’s Singing Jockeys, the Bryn Pugh Sponge Dancers, Madame Zaza (the Filleted Female Nude), Professor Cheer (The Man with a Xylophone Skull) and the Catholic Geese of the title.

It’s a book about art and entertainment, audiences and theatres, the bizarre and the brave, like George Formby, “Last artiste to leave Dunkirk, first back/after D-Day, buck-teeth bared/against the bullets.”

Yellow is the colour of summer and the colour of money, of New York taxis, TNT, sunflowers, cowardice, the earliest pigments found in palaeolithic cave-art and the stars Jews were forced to wear during the nazi nightmare.

In her new collection, Dangerous Pursuit of Yellow (Smokestack, £7.99) Annie Wright explores the colour’s contradictory associations. It is a book about nature and art, kitchens and bedrooms, about yellow-fingered munitions-workers in the second world war, Frida Kahlo, the volatile, fading colours of family memory and the economics of a colour like saffron:

“Beware my bitter curse: blood-orange nightmare,/aromatic ruin. Wars have been fought and lost/in my name. This year I might manifest/or not, ruby purple bleeding into apricot and gold./I will bankrupt your days, desiccate your nights,/dye the winding sheet, dance with the funeral flames.”

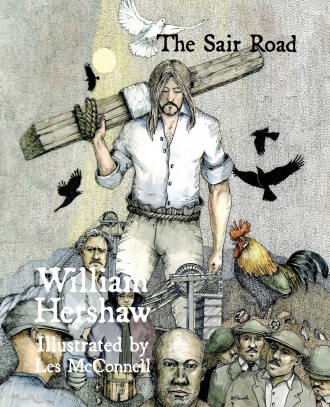

William Hershaw is a folk musician and Scots language activist and his new book, The Sair Road (Grace Note Publications, £20), illustrated by Les McConnell, is based on the idea of Christ working as a miner in the Scottish coalfield:

“Black-listit him fae ilka pit in Fife,/The family evictit, puit out upon the street. Taen in by neebors out the wind and rain,/The wummin o the soup kitchen kept saul/And Body thegither syne.”

It’s a very effective conceit, looking back to Edwin Morgan, Joe Corrie and Hamish Henderson, a powerful way of talking about the crucifixion of the NUM in 1984-85, and the subsequent destruction of the mining industry and its communities:

“Condemned by the Sunhedrin Daily Mail,/Thatcher and MacGregor, the BBC,/Chairged wi riot, unlawfou assembly,/The braggarts feart he micht owecowp their world/And like mad dogs settled tae bring him doun./They couldnae thole the wittin that he brocht:/A Christian is a Socialist or nocht.”