This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

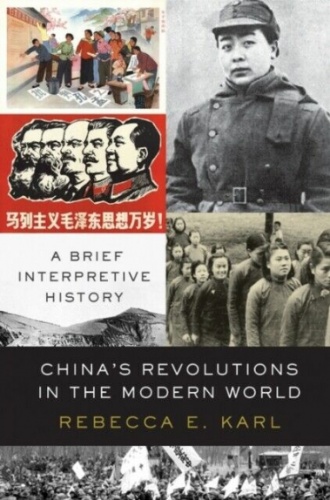

China’s Revolutions in the Modern World: A Brief Interpretive History

by Rebecca Karl

(Verso, £18.99)

VERSO’S latest offering on China is a concise and thought-provoking overview of nearly two centuries of Chinese revolutionary movements by historian Rebecca Karl, starting with the Taiping Rebellion which broke out in 1850.

The book goes on to discuss the collapse of the Qing dynasty, the establishment of the Republic of

China, the May Fourth Movement, the rise and fall of the United Front between the Communist Party and the Kuomintang, the founding of the People’s Republic, the cultural revolution and the reform period from 1978 onwards.

Importantly, the author discusses the links between these processes and explores their connection to contemporaneous events and changes in the rest of the world.

Karl provides a particularly interesting and nuanced analysis of some of the most controversial phases of modern Chinese history — the Hundred Flowers campaign, the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.

While she doesn’t shirk from describing the terrible excesses and mistakes associated with those periods, she manages to avoid the childish tropes usually found in Western historical accounts — Mao as crazed and vengeful dictator being an example.

Instead, Karl describes the incredibly complex domestic and international political context — the deteriorating relationship between China and the Soviet Union and the resulting apparent need for China to be economically self-reliant, along with the heated ideological debates within the Communist Party about how to build socialism in a vast and underdeveloped country that had yet to wipe out feudalism and undergo industrial revolution.

The turbulent history of the relationship between the Communist Party and the Kuomintang is also recounted with skill and subtlety.

Yet in her treatment of the post-1978 “reform and opening-up” era, Karl offers a disappointingly one-sided critique that takes its lead from the more extreme elements of the Chinese New Left. “Socialism with Chinese characteristics” is portrayed as an unfortunate setback, in which socialism has been undone and replaced with vicious neoliberalism and ruthless repression.

Karl’s criticism of the terrible inequality to be found in China today is of course valid and important but it should be balanced with some discussion of how the quality of life has improved for the vast majority of Chinese people.

This rising baseline of human development certainly mitigates rising inequality and helps to explain why the Chinese government retains its popularity and legitimacy.

Deng Xiaoping and his successors are criticised for a strategy in which the “ends” — GDP growth and technical development — justify the “means” of private capital, foreign investment and massive inequality.

But this is a misrepresentation. GDP growth and technical development are not ends in themselves. They are a proxy for improving people’s lives and breaking out of backwardness.

The reform period has achieved extraordinary successes in poverty alleviation, to a point where extreme poverty, illiteracy, malnutrition and homelessness have been all but wiped out for the first time in China’s history. Is it so difficult to see something socialist in this?

In her treatment of the Tiananmen Square incident and the situation in Xinjiang, the author offers little more than a recapitulation of the standard Western narrative of authoritarian Han Chinese leaders riding roughshod over the will of the masses.

Karl certainly doesn’t do her credibility any favours by citing the professional anti-communist and Christian fundamentalist Adrian Zenz in relation to the treatment of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang.

Disagreements aside, China’s Revolutions in the Modern World provides some valuable insight into modern Chinese history. An excellent book to read alongside it is Han Suyin’s biography of Zhou Enlai, which covers similar ground but from a different perspective.