This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

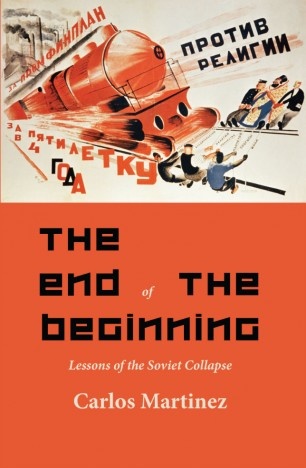

The End of the Beginning

by Carlos Martinez

(LeftWord, £5.99)

I RECALL attending a congress of the Greek Communist Party 20 years ago at which its former leader Harilaos Florakis told delegates that the world communist movement would never advance again until it had come to terms with the collapse of the USSR.

It seems he was right. The Soviet Union expired more than 27 years ago, well over a third as long as its actual lifespan. But still there is no closure. Socialists and Communists continue to work to come to terms with the life and death of the first socialist state.

Thus this small book by Marxist writer and activist Carlos Martinez is a welcome contribution to that continuing discussion. It pulls together a range of explanations for the collapse of the USSR and subjects them to scrutiny. He examines ideological weaknesses in the Soviet Communist Party, destabilisation by the Western powers, mounting economic difficulties and the blunders of the Gorbachov leadership.

Martinez’s analysis broadly follows in the path of Socialism Betrayed by Roger Keeran and Thomas Kenny published in the US some years ago, albeit with less economic analysis and a more muted emphasis on “betrayal” by the party/state leadership.

His position is partisan, regarding Soviet power as a considerable step forward — its achievements are summarised — his prose is lucid and, while his arguments in most cases cover familiar ground, they are no less convincing for that.

There are however omissions in his review of the factors causing the end of the USSR, one or two of them quite striking. The author does not really try to come to terms with the impact of the devastating purges of the 1930s, nor does he give sufficient weight to the absence of any move towards socialism in the more developed parts of Europe in the decades after the second world war.

This left the Soviet Union still confronting a hostile capitalist bloc allied to the US and it deprived socialism of new impetus and political possibilities.

Most importantly, Martinez gives very little space to the failures of Soviet nationalities policies. It is clear that behind the bland phrases concerning the formation of a “Soviet people,” nationalism in fact grew from the 1950s on — to the extent that it had ever been superseded — and national fault-lines were the principal weakness in the Soviet state at the time of its collapse. The persistence of nationalism as a political factor is something the left cannot really ignore.

He is, however, right to emphasise that the descent into chaos from the mid-1980s onwards was not inevitable and another policy could have been followed and, to that extent, Gorbachov was culpable. But the crisis he was trying to address was not a figment of his imagination.

The Communist Party of China has certainly learned the lessons of that experience. But it makes no claim to be creating a new model of socialism. Nevertheless, the title of this worthwhile book expresses the right degree of optimism. The Soviet experience is part of the common political heritage of socialism and future achievements will stand on its shoulders.

In 1981, I visited the North Ossetian Soviet Republic. On asking a young woman how socialism was doing, she answered that Soviet socialism was “OK, but we do not really like to work. Socialism in Britain will be better because you are used to working.”

It was an insightful observation, although the foundations for her optimism have yet to be tested in practice.

Perhaps that will be the next beginning.