This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE Congressional Budget Office reported recently that the federal debt will overtake GDP by next year and will double to more than $33 trillion by 2030.

Debt and sin are synonymous in Christian thought and liturgy: “Forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors” runs the Lord’s Prayer as recited by Presbyterians.

Is it a coincidence that red is the colour of sin, negative numbers on the balance sheet, and the Republican Party — not to mention Donald Trump’s face?

From the indulgences sold by Pope Julius II to build St Peter’s in the 16th century, to the High Priest of Reaganomics David Stockman, a one-time student at Harvard divinity school in the 1980s, theology and economics have been two sides of the same coin.

“Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s,” said Jesus, inspecting a Roman denarius presented him by the Pharisees.

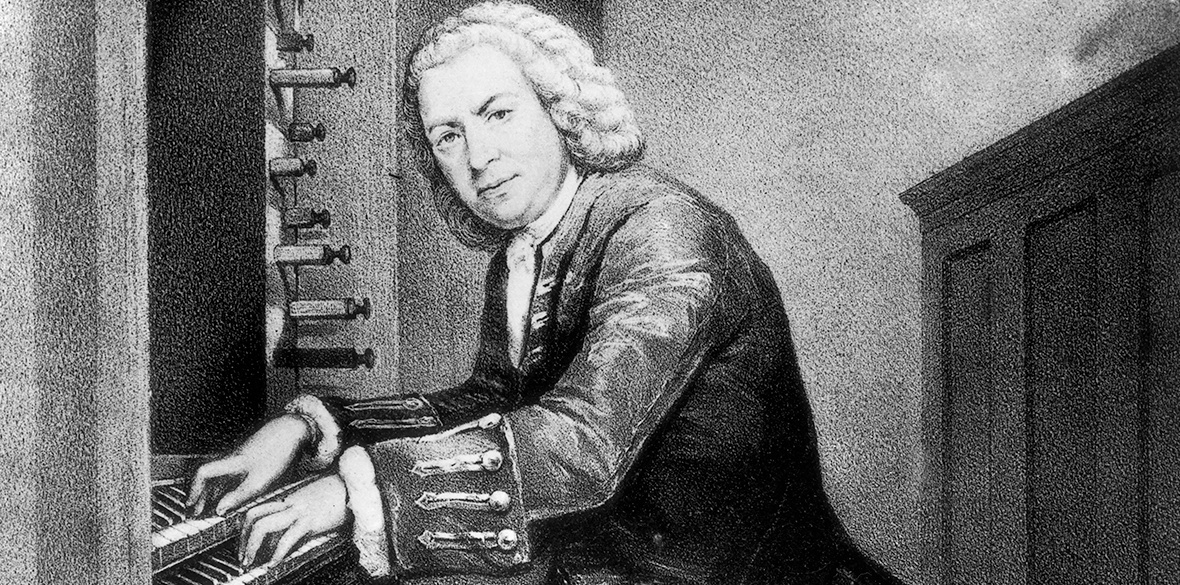

Nearly three centuries ago, Johann Sebastian Bach also grappled with money and sin through music.

Bach composed his Debt Cantata within the span of a few days, leading its first performance on the July 29 1725 in Leipzig, almost exactly 25 years before his own death.

The Gospel for that day in the church calendar was taken from the 13th chapter of Luke.

This passage relates the parable of the unjust steward in which a manager is accused by his rich employer of squandering the goods entrusted to him.

The manager then proceeds to cut deals with the wealthy man’s debtors on the theory that once fired, the manager will need a place to stay, and decides to forgive some of these debts without informing his boss.

The parable has caused more than a little confusion and consternation among interpreters, especially those who attempt the difficult task of explaining Jesus’s apparent endorsement of duplicitous financial dealings, while he simultaneously argues for a downward redistribution of wealth.

Many wealthy Christians like to skip over the passage’s closing line: “No servant can serve two masters … Ye cannot serve God and mammon.”

Not so our Bach, who musically depicted this dictum with unmatched ferocity.

The fiscal parable from Luke was an alluring one for Bach’s librettist, Salomon Franck.

Franck had been the court poet in Weimar when Bach had been employed there between 1708 and 1717.

The two had begun to collaborate in earnest in 1714, when Bach was elevated from the position of court organist to that of konzertmeister and in this new capacity was charged with producing one cantata every month (as opposed to one a week in Leipzig).

Aside from being a man of letters, Franck was also director of the ducal mint in Weimar, which helps explain the frequent appearance of monetary images in his poetry.

Franck provided the text for another of Bach’s fiscally oriented Weimar cantatas, Nur Jedem das Seine (BWV 163) (To Each His Own), which treats the touchy subject of taxes, and includes a moving central aria in which the human heart is likened to a coin to be minted by God.

Bach had left the Weimar court some eight years before writing his Debt Cantata in July of 1725 to become director of music in the much larger city of Leipzig.

Also something of a coin collector, Bach may have returned to Franck’s vivid text because the poet had died just two weeks before.

The cantata, which treats the big themes of money and death, might be heard not simply as an expansive musico-poetic interpretation of Luke’s Gospel, but also as a tribute to Bach’s former collaborator and fellow numismatist.

The cantata begins with the upper and lower strings chasing each other breathlessly through the orchestral introduction before the brimstone bookkeeper of a bass incessantly repeats his demand that the listener “Thue Rechnung” — “Make an accounting,” or, more colloquially, “pay up.”

In the opera house this music would have suggested a storm at sea; in the church it is a tornado that sweeps through the moral ledgers.

The music becomes still more frantic with the “word of thunder” that demands payment by the Almighty in a voice that “crumble cliffs and “freezes the blood,” the latter image brilliantly evoked by Bach through a long-held note low in the bass’s register.

The ultimate payment will come at death when the Banker in the Sky will evaluate all “goods, body, and spirit.”

The Day of Reckoning is itself a financial metaphor, and to be in debt to Him is to be terrified.

This bracing aria is followed by a grimly restrained tenor recitative conducted in a kind of bureaucratic language.

The music tries to remain icily objective, yet it can’t always contain the underlying angst below boasts of “office and position.”

Explicit reference is made to the Unjust Steward: when God takes an unstinting look at the accounts and the “selfish squandering” of his gifts, his response will austere, angry.

Perhaps suggesting the slow and earnest accounting to come, two oboes d’amore sustain their sonority throughout the twists and turns of the harmonies, like a pair of unfailingly assiduous comptrollers.

The unstinting look at personal moral finances continues in the ensuing aria: “Kapital und Interessen” (Capital and Interest).

In his Bach biography, the humanitarian, organist and scholar Albert Schweitzer, clearly put off by Franck’s penchant for talking about money in a sacred context, dismissed the aria as unworthy of Bach.

I hear it differently. The unison oboes d’amore offer up a courtly dance suggesting the easy, leisure-filled life of the “capitalists,” defined in 18th-century Germany as someone who lives off his rents and investments.

The music is smooth, untroubled but also insinuating, with the oboes sometimes elegant to a fault.

However rich one is, there is always an accounting: “Capital and interest, / My debts large and small / Must one day be reckoned./ Everything that I owe is written in God’s book / as if with steel and diamonds.”

The ledger of eternity is not calculated with computers and obscure financial instruments, but cut with heavy, screaming machinery, perilously high for the bass voice.

The cufflinked capitalist will have to bare his soul and his tax returns. The Last Judgement is the final audit.

In strident tenor tones, the next recitative enjoins sinful debtors to come before the Great Creditor in the knowledge that He will cancel all debts through the “blood of the Lamb.”

Luther’s reformist theology rejected good works as the path to heaven, claiming instead that faith alone guaranteed salvation.

Nonetheless, good works could be taken as a sign of underlying faith, and the closing sentence of the recitative urges earthly altruism: “However, since you know / That you are a steward,/ Be careful and not forgetful,/ To use money wisely,/ To help the poor,/ Then you shall, when time and life end,/ Rest securely in the courts of heaven.”

The recitative relaxes into soothing arioso that evokes the calmed conscience of the Good Steward.

These noble words usher in the impassioned soprano/alto duet that is the climax of the cantata, one that urges a rejection of money-making for its own sake: “Heart, rend the chains of Mammon,/ Hands, sow goodness!”

The suave oboes are now silenced. A minor-mode descending bass-line, its contours long a symbol of death and despair, pulls down the spirit.

This bass-line tries to escape the inexorable gravity of the chains of Mammon with upward ascending figures — artful shrieks. But the chains are too strong. Above this remorseless descent, gulping for air from above, the two vocal parts battle towards the good.

Their crying upward-fighting arpeggios dramatise the desire to “rend the chains” even as the close, enmeshed suspensions between the voices portray the unbreakable strength of Mammon’s shackles.

As always the moral injunction matters most in the final reckoning of death, and here the duet becomes somewhat sweeter, almost consoling, but for the stabs of the bass-line and occasional slashes of the vocal figures: “Make my deathbed soft,/ Build me a solid house / Which will last forever in heaven / When the goods of earth turn to dust.”

There is no more harrowing a duet in Bach’s oeuvre. The classic performance of it is from Nicholas Harnoncourt and the Concentus Musicus of Vienna with two boys, Christian Immler and Helmut Wittek, as soloists.

Theirs is a powerful rebuttal of the claim that such pieces exceed the abilities of Bach’s Leipzig boys, and it is worth listening to again in light of the now-favoured view that only male falsettists sang the treble arias of Bach’s demanding sacred music.

The pure, determined, but slightly unstable voices of Immler and Wittek imbue the duet, even when it makes consoling overtures, with electrifying terror.

Appropriately, in the cantata’s final placid chorale, there is no talk of money and debt, but only of faith in God at the moment of death.

Bach’s own financial house, it has to be admitted, was not in great shape when he calmly departed his cramped Leipzig quarters in the last days of July 1750 for the spacious apartments of heaven, vaulting his widow and two young daughters into much straitened circumstances.

In that Sunday in July of 1725, though, the Leipzig rich had something to ponder (if they were listening) as they sat in the front of the church in their rented seats, while the poor milled around at the back of the church.

Like the parable on which it is based, this cantata invites diverse interpretations.

But Bach’s Debt Cantata demands that you listen not to the financiers and politicians, but to your conscience.

This article first appeared in Counterpunch.org. David Yearsley’s latest book is Sex, Death, and Minuets: Anna Magdalena Bach and Her Musical Notebooks.