This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

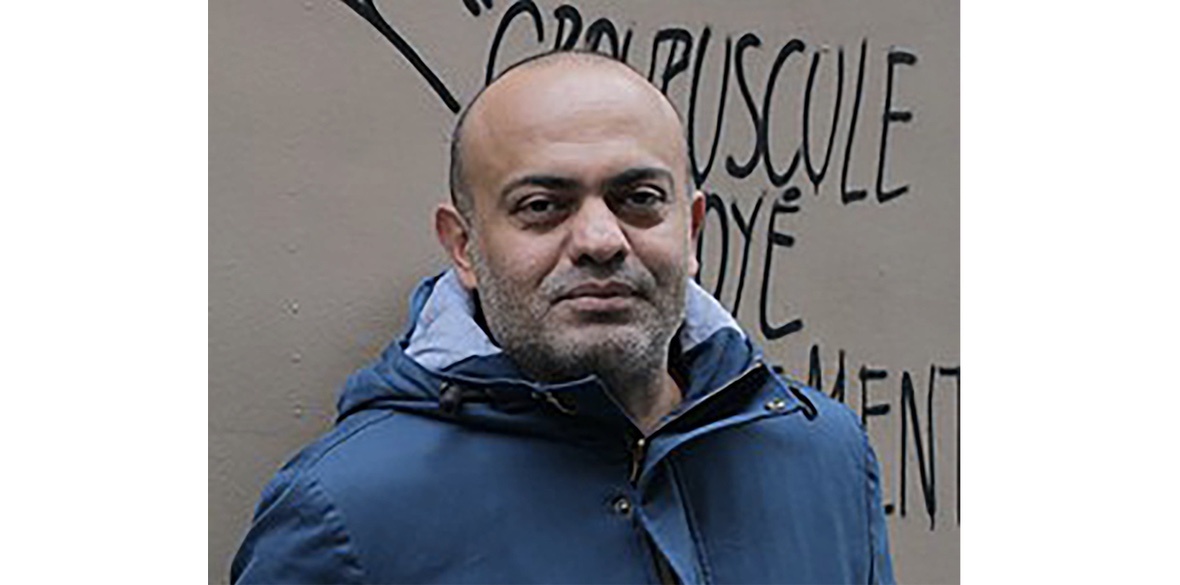

“PLEASE be patient with my English,” says Hassan Blasim before launching into a cogent and enlightening discussion of his first novel, God 99.

“I wanted to call the book Allah 99, as a little joke for the Arabic press. God has 99 names in Islam, and refugees have many faces — they aren’t just an army of zombies wandering into Europe.”

Born in Baghdad in 1973, Blasim attended the city’s Academy of Cinematic Arts, winning awards and attention for his work as a director and scriptwriter. Sadly, some of that attention came from the Ba’athist authorities and led to harassment and arrests.

“The Ba’ath party didn’t like what I was doing,” he says. “They worried about people on the arts scene and I was getting the message ‘don’t go too far, be careful’.”

“I feared the power of the secret police. They could kill you. Even now, you can’t joke about religion and you can’t talk about free speech. I sometimes say refugees are the victims of free speech because there are so many of them in prison for writing about it.

“The world is often described in Twitter slogans,” he says over a patchy video connection between Finland and Nottinghamshire. “Politicians and the media fear writing that talks about people’s lives in depth.”

In 1998, on the advice of his tutors, Blasim fled Baghdad for Sulaymaniya (Iraqi Kurdistan) and made Wounded Camera, a feature-length drama. The film was credited under a pseudonym to protect his family from Saddam Hussein’s regime.

From Sulaymaniya, Blasim began a long walk across borders, all the way to Finland. In 2004, after years as a refugee, Blasim settled in Helsinki. There, he made films, wrote articles and produced a pair of acclaimed short story collections, The Madman of Freedom Square (2009) and The Iraqi Christ (2013), both published by Comma Press.

God 99 focuses on Blasim’s love of literature — his enthusiasm for the work of Calvino, Beckett, Camus and Borges is clear — and the kind of persecution that drove him to leave Baghdad.

“There are subjects you can’t touch in the Arabic speaking world. In this book I wanted to ask questions about great literature but I also wanted to talk about the lives of refugees and the experience of exile.

“So I mixed poetic language and ‘cheesy’ street talk. I set out to create a dialogue between life and death, with meaning revealed by changes in tone and language.

“I changed the language to make each story work — some scenes mix classic Arabic with the kind of sexual directness you find in the books of Henry Miller. I’m not sure that Western readers will understand the taboos being broken, or the shock this kind of writing causes in the Arabic-speaking world.”

God 99 is a storehouse of revulsion and wonder. Lurching between erudition and bawdiness, quiet contemplation and sudden violence, the book is a maze of tales within tales, in the manner of the Arabian Nights and Jan Potocki’s The Manuscript Found in Saragossa.

Some of the narrative threads are linked by theme, others have overlapping events and characters. I ask Blasim if the labyrinthine structure was something he planned in advance or if it emerged from the experiences of his exiled characters.

“For any storyteller, there’s what you want to do but there is also what the story tells you to do,” he tells me. “I had a lot of life experience to talk about, maybe too much, so I planned to tell stories within stories from the start.

“I like the form, because it reflects the experience of being human and the history of humanity. It fits the way we live our lives.

“I was writing about my life, so there is a character called Hassan, but there are other migrants inside Hassan, other refugees speaking through his mouth and expressing different ideas. I was interviewing myself but also interviewing fictional characters. Readers may miss a joke or idea but I hope everyone will gain something from the book.”

At one point in the story the narrator, known as Hassan Owl, declares that places no longer arouse his curiosity or emotions. Does this sense of dispassionate dislocation stem from the experience of exile, or is something else is at play, I ask Blasim.

“There have been good and bad situations in all the cities and countries I have been to. I think you can put down roots anywhere but a real sense of place comes only from experience. For me, the world is like a hotel and exile is a gift for any human being. It changes you and lets you disappear into different cultures.

“I wanted to write a book about borders. Where is the border between human beings? Where are the borders between home and exile, peace and war, belief and non-belief?”

Breaking down borders comes at a cost, of course. During Blasim’s walk from Iraqi Kurdistan to Finland, refugees were insulted, assaulted, raped and tortured. And his life in Europe has not been free from racism.

“Racism is a disease that is becoming worse and it’s deeply embedded in Scandinavian society and culture,” he says. “It is used by politicians whenever there is a problem with the economy. The only way to combat it is to teach kids about its roots and causes.”

Hassan’s key relationship in God 99 is with Alia, an enigmatic mentor, translator and philosopher. Alia’s emails are reflective, scholarly and wise, the counterpoint to Hassan’s dialogues of disaster, death and sex. I ask if the character of Alia was introduced to remind readers of our ability to transcend instinct, desire and the grim struggle for survival.

“Alia’s emails were ones I received from Adnan al-Mubarak — I copied them for the book. He was an Iraqi writer and philosopher, a man who had been isolated all his life, translating books and writing about science fiction. Our friendship began when I wrote to him via a website and he sent a nice email in return.

“Whenever I crossed a border it was his voice I heard inside my head. He gave me lessons in literature and became a person who touched me. His voice was unique. because he was born in Iraq but grew up in Poland, in the Western intellectual tradition. He is dead now.

“I made him a female character in the book, a Scheherazade with a difference — the words of Alia keep him talking and that means he is still with me.”

God 99 by Hassan Blasim is published by Comma Press, price £9, and is available in bookshops and from commapress.co.uk