This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Life Between Islands

Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now

Tate Britain

I HAVE to start this review of a fantastic exhibition by acknowledging I write as a poet and not an art expert.

Having said that, I was filled with admiration for the curators who have managed to assemble an impressive body of work, ranging from sculptures to paintings, installations to photographs. These all help to tell the complex story of the interplay and interdependence that has been created between the Caribbean diaspora and Britain over the last 70 years.

If I have one complaint it’s that there is so much amazing work it’s impossible to take it all in during one visit. Not a bad criticism to make.

The first room contains two astonishing sculptures by the Jamaican-born artist Ronald Moody, both of which seem to say so much about the complex nature of power.

We are greeted by Johanaan, a larger than life-sized male torso carved in elm that contains the most magnificent strength and prepares us for the incredible power of the work to follow.

The statue’s arms are rigidly at the sides and the hands are buried in the short wooden plinth. I understand that classical torsos are often shown without arms but in this case I was led to wonder what is being said about the nature of power without the use of one’s hands?

Another sculpture by Moody, The Onlooker, literally made me jump as I had not seen the squat figure of a man placed in the corner of the first room. When I turned round, I was met by a powerful piece that depicted someone hugging themselves in a way that seemed self-protective/defensive.

This appears to undermine the apparent bulk/weight of the work and the fact that it’s carved from teak, one of the strongest of timbers.

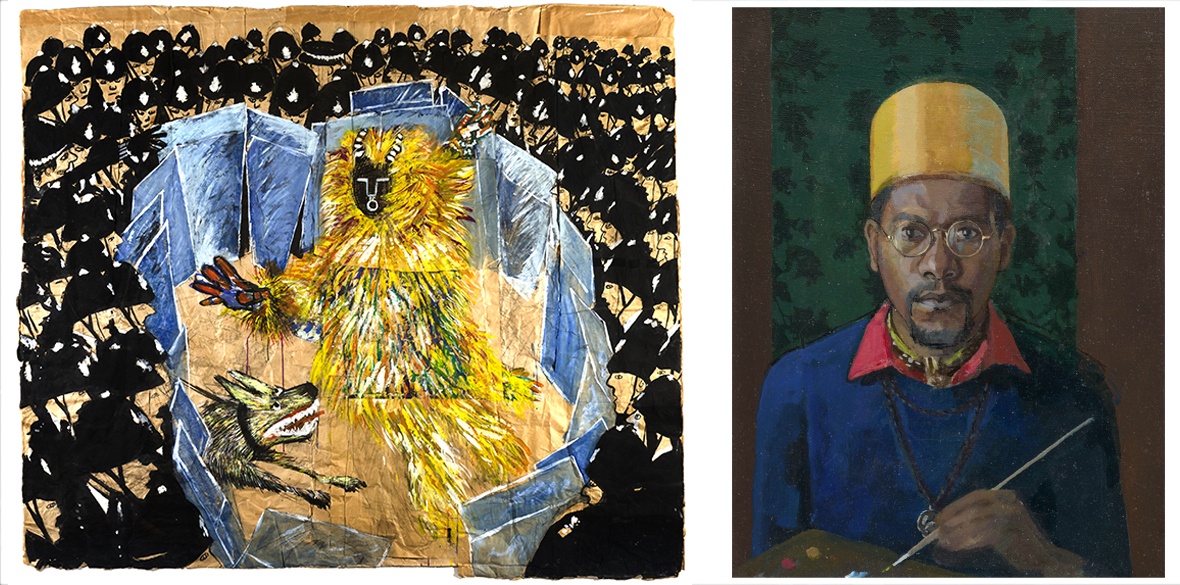

Elsewhere, there is a small but magnificent painting by the Barbadian artist Paul Dash — apparently the only self-portrait he ever did — that I think evokes the notion of the “great artist.”

He depicts himself with palette and paintbrush in hand, wearing a vibrant yellow hat. Although his clothes suggest a link to the Black Power Movement of the 1970s, the pose and arresting gaze mirror Rembrandt’s self-portraits. Dash is a black artist proudly and boldly staking his claim to be part of a long artistic tradition.

Trophies of Empire, a cabinet of ceramic cylindrical forms by the Guyanese mixed-media artist Donald Locke, is a triumph, being both beautiful and deeply disturbing. The objects are lushly decorative, although they also seem to be unambiguously phallic.

This is unsettling as some of the shapes are held in manacles and could be seen as large candles. The connection to enslavement and fire seems clear, making a dark and deeply serious comment on the destructive nature of empire and enslavement.

Michael McMillan, the British-born artist, shows an immersive installation of the front room of an imagined young woman called Joyce, who is from St Vincent, which is where the artist’s family is from. It echoes his installation The Front Room that showed some years ago at the former Geffrye Museum now Museum of the Home in Shoreditch.

What struck me was not the undeniable detail of the installation but that it was filled with visiting white people who Joyce may never have entertained in real life. I asked one of them what the piece said to her, and she spoke about growing up in a working-class family in London. It was striking that someone who was so apparently different from Joyce had found the work so evocative of her own life.

A painting that will stay with me for a long time was The Spirit of Carnival by the Dominican-born British artist Tam Joseph. It depicts a gang of policemen with shields, circling a black person who is wearing the costume of a Yoruba Egungun figure. It looks as if he/she has been unequivocally trapped.

However, there is an irrepressible fire in the colours of the costume, and it struck me that the outstretched hand is painted in red, white and blue. This suggests there is much more to the image than defeat.

The well-known painting by Sonia Boyce’s She Ain’t Holding Them Up, She’s Holding On, is deservedly reproduced as the exhibition’s publicity poster. It shows a black woman literally supporting her family in a pose that is monumental but also exudes effort and sadness. It seems to convey so much — along with the inspired title — about how difficult it is to maintain power, and the impact this has on the family.

I would urge everyone who can visit this exhibition to do so before it closes on the April 3 2022. Finally, I need to mention Tate’s gallery assistants, volunteers and staff who couldn’t have been more helpful.

Until April 3 2022. Box office 020 7887 8888,

shop.tate.org.uk/life-between-islands-exhibition

Jenny Mitchell’s collection Map of a Plantation is winner of the Poetry Book Awards 2021. For more information go to: indigodreams.co.uk.