This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IT’S not often that the British empire is considered as a significant force in the Americas.

Of course, its crown colonies in the Caribbean and a string of former island possessions are well known, though the colonies of British Honduras (now Belize, which still has Elizabeth II as head of state) and British Guiana (now Guyana) are perhaps less noted.

While it is true that Britain always maintained an informal empire in the western hemisphere, which took in massive interests in places like Chile and Argentina, much of that is now largely subsumed into Anglo-US interests.

Britain was responsible for bringing slave labour from west Africa to carry out the one staple industry of British Guiana — sugar production.

Imported slave-like indentured labour from India followed. The seeds of a modern divisive racial politics, developed by Britain and then the US, lie in this history.

Until the 1970s, British Guiana was almost entirely controlled by one British firm, Bookers — sponsor of the prize, absorbed by Tesco in 2007.

Bauxite was the second major product, needed for aluminium aircraft production. Again one company dominated output, the British Canadian firm, Demerara Bauxite (Demba).

In the 1950s, the economy of Guiana was larger than most American countries — even if its citizens were mostly poor.

Today Guyana’s economy is weak and it has an infant mortality rate of 47 per thousand compared to 3.8 in Britain.

British colonial rule rested on manipulating the country’s two main population groups. But a strike by sugar workers in 1948 was fired on by British troops, killing both Indians and Africans.

Tension from this led a British Labour government in 1951 to grant the colony a constitution with limited internal self-government under the overall rule of a British governor-general.

Out of workers’ struggles, the People’s Progressive Party emerged, seeking to unite workers from both backgrounds.

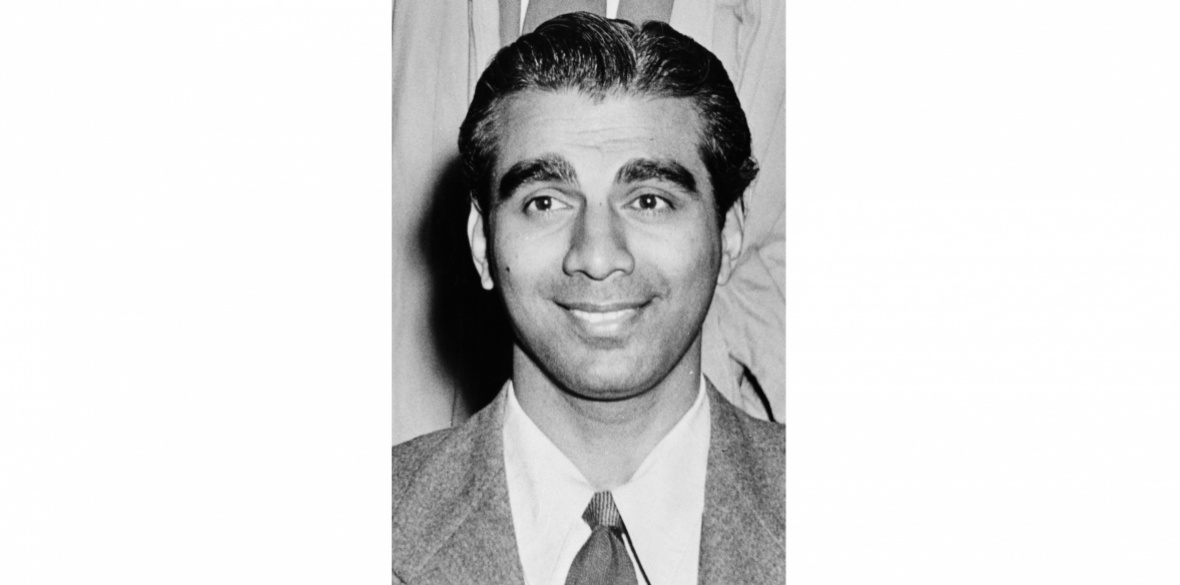

In elections in 1953 the PPP won 18 of the 24 seats and Cheddi Jagan became prime minister, elected on a programme of further democratisation.

Within three months the British government, now with Winston Churchill once again as PM, declared a state of emergency, flew in additional troops, dissolved the parliament and arrested Jagan.

His wife, Janet Jagan, a former member of the Young Communists of the USA, spoke by telephone to the British Daily Worker on October 7.

Five days later she wrote the front page elaborating the PPP’s call for a boycott of British goods and a “colony-wide general strike against the repressive action of the British government.”

A campaign of non-co-operation and non-fraternisation was also begun by the PPP, and Arthur Clegg, the Daily Worker’s colonial affairs reporter, was deported from Guiana.

On October 14, the Daily Worker ran Cheddi Jagan’s cabled reply for the world to see on its front page.

An alleged communist plot was “a smoke screen,” an “excuse to destroy the progressive movement.” It was democracy itself that was challenged by Churchill’s actions.

Rolly Simms, vice-president of the London branch of the Caribbean Labour Congress, told the Daily Worker on October 19 that “the initials BG are the abbreviation for British Guiana. But they also mean, more accurately, something quite different— Bookers’ Guiana.”

Now running the colony, the British government sought to split the PPP on racial lines, claiming to have identified destructive extremism that was countered by positive moderation.

In support of this, the CIA channelled funds to anti-PPP trade unions. Its efforts were mainly focused on dividing the trade union movement on racial lines and the international department of the British TUC played a major role in this.

Nonetheless, when new elections were held in 1961, the PPP won again and Jagan once more became prime minister.

US interventions prompted the British government to declare a new state of emergency in 1964. US operatives funded a programme of destabilisation that culminated in race riots in which 160 people were killed.

A newly rigged electoral system saw the PPP lose in 1966 and Guyana increasingly ruled under a dictatorial system.

Partly in response to all this, the Movement for Colonial Freedom (MCF) was founded in 1954. An amalgamation of the British branch of the Congress Against Imperialism, the Central Africa Committee, the Kenya Committee and the Seretse Khama Defence Committee, the MCF played a key role in decolonialisation, going on to anti-racist education work from the 1970s as Liberation.

British imperialism finally morphed into, first, economic neocolonialism and, under Tony Blair, advocation of “liberal interventionist imperialism,” the latter word becoming widely accepted after the Iraq debacle.

MCF’s archives at Soas are an invaluable resource for understanding imperialism, desperately needing digitisation.

This could remedy the absence of study of the empire in Britain’s national curriculum.

Only in 1992, after the leader imposed by British-US imperialism had died, did Cheddi Jagan once again become leader of Guyana followed by Janet Jagan. By then, Guyana was a victim of intensified underdeveloped exploitation.

Nowadays, Guyana is under the thumb of the US, although the PPP remains progressive and powerful.

A maritime border dispute between Guyana and Suriname was resolved in 2007, clearing the way for US firm ExxonMobil to successfully search for oil in the Atlantic Ocean.

Any attempt to control that wealth for the Guyanese people will surely attract a swift response.

Graham Stevenson is a historian and Morning Star columnist and a national council member of Liberation.