This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

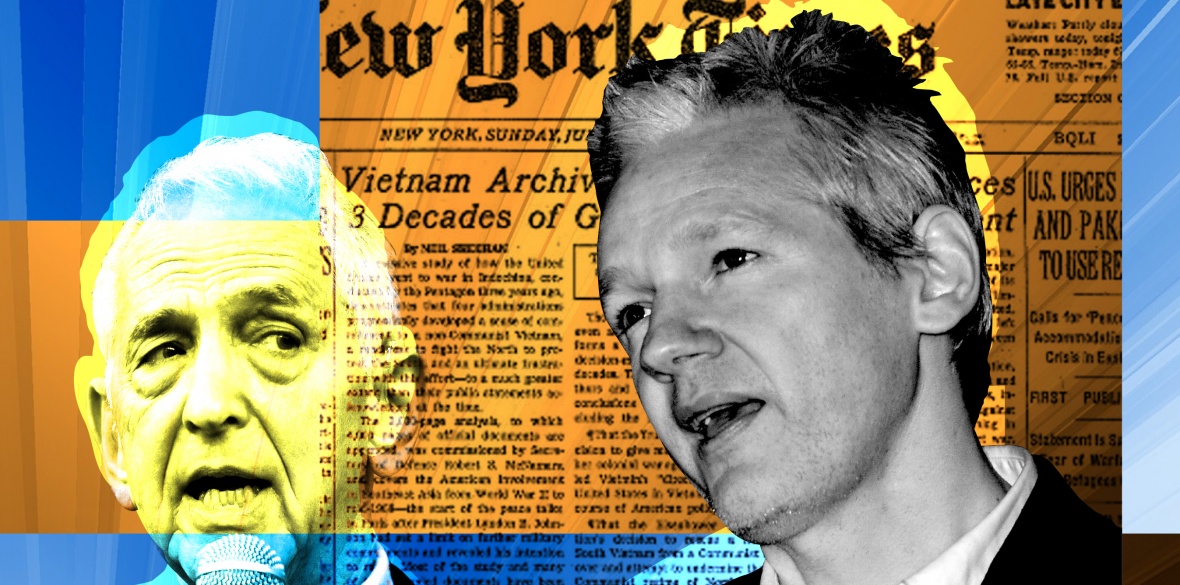

ON May 3 1972, Daniel Ellsberg spoke at a peace rally in Washington DC.

It was a year since he had leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times and the Washington Post revealed that successive presidents had lied about US involvement in Vietnam.

What Ellsberg didn’t know, as he stepped up to the microphone on the steps of the Capitol building, was the the crowd had been infiltrated by CIA “assets.”

Their instructions were to “break both his legs” or even kill him.

President Richard Nixon had personally acquiesced to the planned assault during a meeting with Henry Kissinger.

The attack, however, was aborted as the speakers took to the rostrum.

It was not, though, to be the last of the Nixon administration’s dirty tricks to “get” the former marine, whose whistleblowing did much to bring the Vietnam war to an end.

At the time of the speech, he was already facing charges under the Espionage Act with a 115-year jail term.

When his trial started in January 1973 he was forbidden from explaining to the court his motivations for leaking — despite having revealed for the first time the secret bombing of Laos and Cambodia and the gravest lies by a succession of presidents.

And one of Nixon’s senior staff members had secretly offered trial judge Matthew Byrne the top job in the FBI if Ellsberg was convicted.

By chance, his trial ran concurrently with the Senate Watergate Committee, however.

Day by day, the hearings in Washington brought the various conspiracies against Ellsberg to light. Eventually Judge Byrne felt he had to intervene.

“The bizarre events have incurably infected the prosecution of this case,” he ruled. Ellsberg was acquitted “with prejudice,” meaning that he could never be tried for those offences again.

It is easy to see why Ellsberg, now 89, sees parallels between his own case and that of Julian Assange.

“Wikileaks provided the first unauthorised disclosure of such magnitude for 40 years,” he believes.

“I observe the closest of similarities to the position I faced. The [US government] intended to crush [me] in part in revenge for my act of exposing them but in part to crush all such future exposure of the truth.”

In his evidence to the Wikileaks founder’s ongoing extradition hearing, Ellsberg says: “I have followed closely the impact of [the Wikileaks revelations] and consider them to be amongst the most important truthful revelations of hidden criminal state behaviour that have been made public in US history.

“I view the Wikileaks publications of 2010 and 2011 to be of comparable importance [to the Pentagon Papers].”

Ellsberg worked with Assange at the height of the Wikileaks. They met several times and Ellsberg held one of the encrypted back-up copies of leaked US military files on behalf of Wikileaks.

“I have also spoken to [Assange] privately over many hours. During 2010 and 2011, at a time when some of the published material had not yet seen the light of day, I was able to observe [Julian’s] approach. It was the exact opposite of reckless publication and nor would he wilfully expose others to harm.

“Wikileaks could have published the entirety of the material on receipt. Instead I was able to observe but also to discuss with him the unprecedented steps he initiated, of engaging with conventional media partners, [to maximise] the impact of publication [so] it might [best] affect US government policy and its alteration.”

Cross-examined for the US government by James Lewis QC, it was put to him that there was a critical difference between himself and Assange.

Ellsberg had purposefully kept secret four chapters of the Pentagon Papers because he did not wish to jeopardise efforts for a negotiated peace in Vietnam.

Ellsberg dismissed out of hand the frequently made assertion that “the Pentagon Papers were good and Wikileaks bad,” robustly stating his view that the government’s behaviour was the same in both cases.

If anything, Assange took a more sophisticated approach to redaction than he had been able to, he says.

“For years I was vilified in many quarters,” he told the court. “Only since the Wikileaks revelations have I been praised as some kind of foil to Assange, Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden.”

He says, however, that Assange uncovered a dark change in US military behaviour.

“The most shocking aspect of the Wikileaks revelations is that corruption, torture and assassination have become so common that they are not even classified top secret.

“When I was an officer in the field, or when I was compiling the Pentagon Papers, incidents of this kind would have been given the highest possible classification.

“Today, they have become so normalised that they are in files to which literally thousands of people have access.”

Ellsberg has always maintained that his actions were those of a patriot.

“The oath of office that I took was to defend the Constitution of the United States,” he says, making clear that he considers his actions to be true to that commitment.

Nonetheless, he still feels a weight of responsibility for not acting earlier, he says.

“I have long regretted not releasing the documents in August 1964, and it is a heavy burden for me to bear. Had I done so that terrible war might well have been averted altogether.”

His whistleblowing did presage a change of direction in US policy, but not before nearly 400,000 military personnel and as many as four million civilians had been killed.

Wikileaks’ Afghan and Iraq revelations came far more quickly after those conflicts and, according to other expert witnesses to the hearing, they caused a similar sea change in public perceptions of those conflicts.

Ellsberg suggests that the Afghan war logs exposed the “Vietnamisation” of that conflict in which a military stalemate led to the civilian population no longer been recognised as human beings, resulting in crimes against humanity and mass killings of the worst kind.

Today Ellsberg lives in northern California with his second wife Patricia Marx.

His devotion to working for a better world is undimmed. Three years ago he published his third book, The Doomsday Machine: Confessionals of a Nuclear War Planner, about his working life before the the Pentagon Papers.

He remains a director of the Free Press Foundation, of which he is co-founder, and retains academic affiliations with two universities.

He also remains in no doubt that he and Assange are brothers in arms.

“The prosecution he faces [is] clearly focused, fairly and squarely, at the centre of political movements of which I regard myself as part and which much of my life has spent committed to pursuing.”