This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

WHEN the body was brought to Moscow on Saturday June 14 1924, it was received by deputations from the Soviet government, the Red Army, Russian factories, the Comintern, the Youth International and many of the world’s new-born communist parties.

The four Communist Party representatives from Britain carried a wreath on which was inscribed: “To the memory of a great South African fighter.”

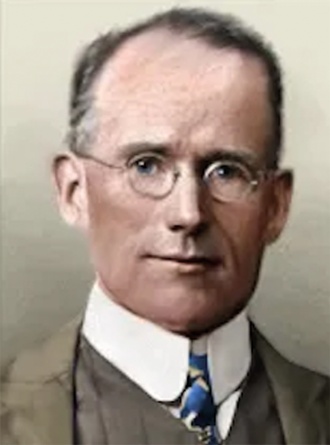

Except that the dead man was not South African at all. He was a Welsh-speaking native of Aberystwyth in Cardiganshire, a former preacher in the town’s Unitarian chapel and an ex-correspondent for the West Wales Gazette.

That paper had once carried his weekly musings on everything from Greek philosopher Diogenes and the Caer Alltgoch hill fort to English revolutionary Oliver Cromwell and the beauty of Welsh in its South Cardiganshire dialect.

A hill-farm orphan raised, like his sister and brothers, by relatives, he devoured the printed word from an early age, leaving elementary school to work in the family’s grocery business in Aberystwyth and nearby Lampeter.

His sermons were a little unorthodox, generally popular and increasingly controversial. They reflected his support for what was, in 1905, the radical liberalism of David Lloyd George.

But he was dogged by a chronic strain of the dreaded tuberculosis. This drove him to seek a healthy life on his brother’s sheep farm in New Zealand.

On the last leg of his voyage, from Colombo to Fremantle in March 1907, David Ivon happened upon two outlawed Russian revolutionaries aboard the steamship Omrah. In a letter to his lifelong friend and mentor George Eyre Evans, he painted a striking portrait of these courageous and erudite men. Their impact on him became evident in later years.

He found the life and work Down Under reinvigorating, tough, worthy, but dull. One bright spot was the absence of any property qualification — “not so much as a pig-sty” — attached to the franchise.

At a time when suffragettes were being jailed and assaulted in Britain, the women of New Zealand were exercising their right to vote in order to frustrate the plans of big-business brewers to reform the licensing laws.

All the while, Jones kept in touch with social, cultural, theological and political affairs in Wales and Britain, in voluminous correspondence with his Evans and on a generous diet of Welsh, English and Antipodean journals.

In a short time, he was off again, this time to his brothers’ stores in the Orange Free State, South Africa. This was in a period of violent class struggle between the goldminers and coalminers on the one side, and their brutal bosses — the “Randholders” — on the other.

Most of the white miners were Dutch or English and some were Welsh, who created a fragile unity to build a trade union movement in the wake of the Boer war. They also directed the labour of a growing number of African labourers who did the dirtier work for far less money.

Jones had admired the Dutch Afrikaners at first, having sympathised with their struggle against the British empire. But what he saw as their coarse, uncultured narrowness and a callous lack of humanity in their dealings with native black Africans quickly dispelled such romantic illusions.

Nonetheless, working as an office clerk in a power station and then as an organiser with the Transvaal miners’ union, he supported the white workers who struck to defend their livelihoods. But more than that, Jones also saw the need to find common cause with the super-exploited black workers being imported into the mining industries.

He welcomed the formation in 1912 of what became the African National Congress. Around this time he joined the all-white but fast-growing South African Labour Party (SALP), quickly rising to become the editor of its newspaper and, in 1914, its general secretary. He also began shedding the segregationist outlook common to almost all white workers and socialists in those days.

He championed not only the formation of trade unions for black Africans, later drafting illicit leaflets for the Industrial Workers of Africa, but also the organisational unity of all workers.

The SALP split over the imperialist first world war. Jones braved persecution and thuggery to oppose the slaughter, and suffered prosecution and jail for issuing a leaflet headed “The Bolsheviks are coming!” and addressed “to the workers of South Africa — black as well as white.”

The Afrikaners were divided, too, as ex-Boer General Jan Smuts sided with the British ruling class. Along with Bill Andrews and Sidney Bunting, Jones broke away to form and lead the International Socialist League and then, in 1921, the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA).

However, the Welsh Bolshevik missed the party’s founding conference, having suffered bouts of ill-health and homesickness. These took him to stay with Mrs Evans and Mrs Griffiths in Nice before paying an overnight visit to Aberystwyth in May 1921.

The next stop was Stockholm, then Moscow for the third congress of the Comintern. His report, Communism in South Africa, had already reached the Comintern leadership, impressing them with its wide scope and deep analysis.

His July address to the congress, The Black Question, was remarkable for its sweeping emphasis on the significance of the Indian, Chinese and “Negro” masses of workers in Africa and the US for the revolutionary movement and socialism.

This was a theme to which he would frequently return, not least in his accounts of the “Rand revolt” in 1922, when armed worker-commandos fought pitched battles with troops, police and Boer turncoats and — to Jones’s dismay — launched a savage pogrom against black strike-breakers.

They also raised for the first time the infamous slogan: “Workers of the World Unite and Fight for a White South Africa,” grappling with its contradictory and self-defeating combination of racism and class militancy.

Such was his reputation by this time that he stayed on at the Hotel Lux in Moscow to work with the Comintern, in touch with Lenin, Trotsky and Zinoviev. When his body could bear it, Jones traversed Russia, Crimea and Ukraine, witnessing the ravages of civil war and the heroic efforts of workers to rebuild their economy and society.

His accounts of these travels and his explanations of Russia’s New Economic Policy, relations with the Orthodox church, the conditions of the peasantry, and his translation of some of Lenin’s writings into English for the first time, filled the pages of communist and left-wing publications from Russia and South Africa to Britain, Australia and the US.

Tragically, just three months after Lenin’s death, tuberculosis caught up with him at a prestigious sanatorium in Yalta on May 31 1924, at the age of 40. Legendary trade union leader and Comintern envoy Tom Mann cabled the news from Moscow to the CPSA in Johannesburg.

Jones was buried in the Novodevichy cemetery on the western side of the Russian capital. Fittingly, his grave would later be flanked by those of other exiled giants of the South African liberation movement, JB Marks and Moses Kotane.

In 1924, the name of David Ivon Jones was honoured around the world and remains so in South Africa today. But it is almost unknown in his native Wales and Britain.

That’s why the David Ivon Jones festival on June 28-29 will be celebrating his life and inspiration in Aberystwyth.

An alliance of Labour and Plaid Cymru members, communists, trade unionists, peace campaigners, anti-racists and Welsh Language Society activists is organising a weekend of films, readings and a book launch to remember “the African from Aberystwyth.”