THE distinction John McDonnell draws today between socialist internationalism and “international co-operation [that] has come to reflect the neoliberal economic paradigm” could hardly be more important.

The ability of capitalist institutions, established to advance the interests of transnational corporations, to masquerade as “internationalist” entities is responsible for many of the divisions on the left.

Within sections of the Labour Party the “internationalist” mantle is even draped over war machines like Nato, actually an aggressive imperialist military alliance primarily established to subordinate national militaries to that of its dominant power, the United States.

A highly selective definition of “the international community,” comprising the US and its allies, is often invoked to justify acts of aggression against countries that have offended Washington for one reason or another.

The issue of the European Union is more divisive yet.

Millions have been convinced that support for EU membership is evidence of an internationalist outlook and opposition to it is largely driven by xenophobia or, worse, racial prejudice.

In that light, McDonnell’s reminder of the appalling treatment of the Greek people by EU institutions which forced a devastating programme of privatisation and cuts on their nation is timely.

It is vital, though, that the correct conclusions are drawn from the Greek tragedy. Green MP Caroline Lucas was among the fiercest critics of the behaviour of the EU, International Monetary Fund and European Central Bank “troika” at the time, but has since become one of the most prominent advocates of maintaining EU membership.

Together with supporters of initiatives like Another Europe is Possible or Love Socialism Hate Brexit, she is prepared to attack the neoliberal policies of the EU while supporting membership of it.

If the EU’s policies were democratically decided that might make sense. But as parties launch their European parliamentary election campaigns, it is worth restating that the European Parliament is a toothless talking shop which does not possess the power to initiate legislation.

Policies are decided by the unelected Commission. The binding Maastricht and Lisbon treaties place highly restrictive conditions on when the EU will allow public ownership, how publicly owned enterprises may or may not operate, what public assistance is available to what industries and when, the conditions on which elected governments may procure services and more.

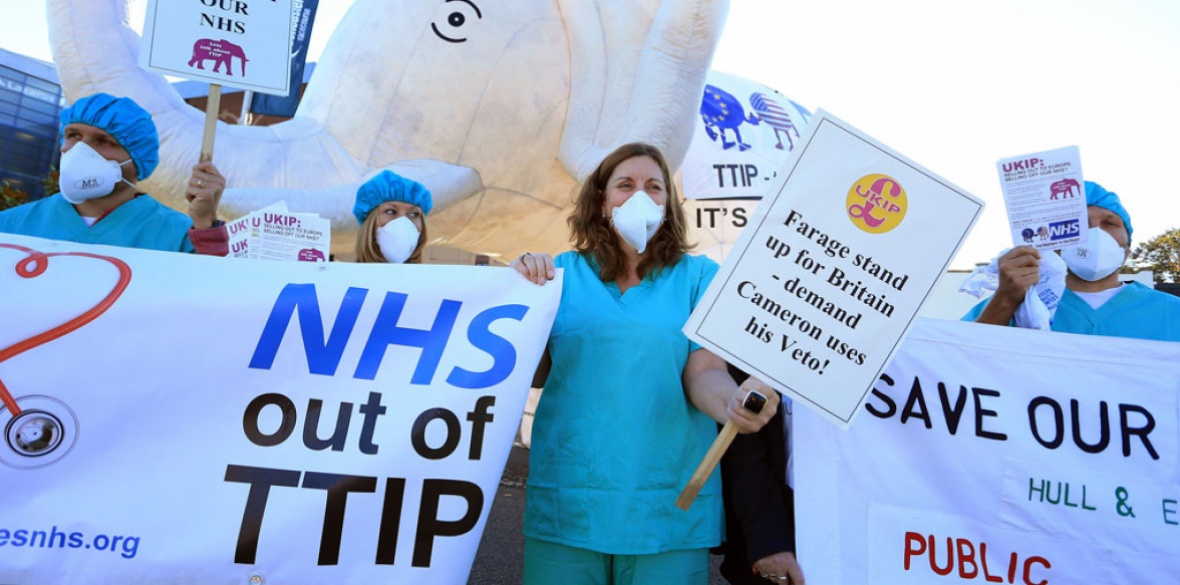

These treaties, no less than international trade treaties like TTIP — which the EU was the driving force behind — are intended to establish a framework in which governments’ right to determine their own economic policies is strictly policed and the will of the people is subordinated to corporate interest.

As Tony Benn once said, they form “the only constitution in the world committed to capitalism.”

Some opponents of Brexit argue that the EU may be a neoliberal institution, but “on its own” Britain would be even weaker when negotiating with transnational corporations or mammoth trading blocs.

The flaw there is to assume that somehow when the EU acts as one it is representing our interests in negotiations with an outside party such as the United States.

But as European commissioner Cecilia Malmstroem told former War on Want chief John Hilary in an interview, the EU “does not take its mandate from the European peoples.”

The TTIP negotiations took place between representatives of European and US corporate interests and both sides aimed at undermining workers’ and consumers’ rights on both continents.

That is why the EU was supremely uninterested in overwhelming evidence that the European public were bitterly opposed to TTIP being negotiated at all.

It also explains why even MPs were only allowed to see what was in the treaty in secure reading rooms and were barred from discussing its contents with their constituents.

Rules designed to smooth the way for transnational corporations may be policed at an international level. That does not make them internationalist. McDonnell’s call to rebuild a socialist internationalism is an opportunity to make this clear.