This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

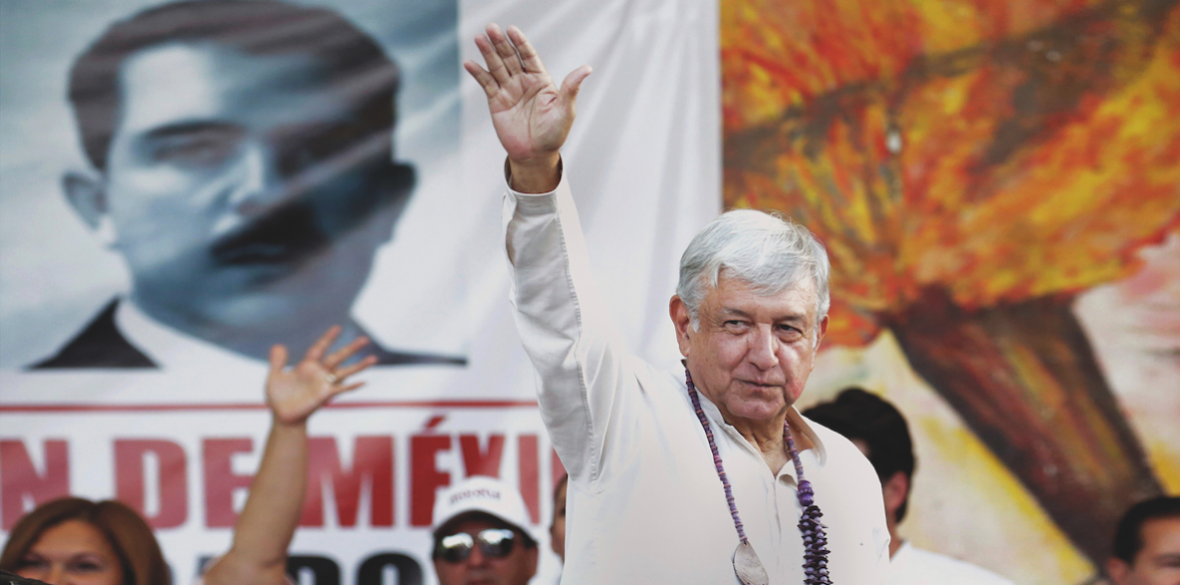

AMLO, Mexico’s President who has led a progressive government since 2018, now has only one year (in fact slightly less) of a six-year term left. He leaves office on September 30 2024, and the elections are on June 2.

While Amlo is as active as ever in implementing his transformative programme, the succession and the general elections (with a new congress at stake as well) now dominate the political scene.

A first step has already been taken with the internal nomination process in the Morena party, which produced a clear majority for Claudia Sheinbaum (former head of government or metro mayor of Mexico City) as leader of the Fourth Transformation movement (meaning in effect she will be Morena’s presidential candidate).

Given the continuing unpopularity of the right-wing opposition, Sheinbaum is very likely to be the next president.

To have a woman at the helm would be a significant advance, but also Sheinbaum has impeccable progressive credentials, coming from the left and with professional training in environmental sciences. Most Morena members, and most voters, believe that the Fourth Transformation will be in safe hands with her in charge.

As always, Mexico faces ongoing problems which are the focus of the mainstream media. Migration from neighbouring countries of Central America (and other parts of the world) is steadily increasing, with Mexico as a staging post for their real destination, the US.

This is an insoluble problem since Mexico cannot control US migration policy; it offers migrants the option of settling in Mexico with access to jobs and benefits, but very few will accept this.

What Mexico has done, to some effect, is to persuade the Joe Biden administration to open up more channels for legal migration, and also to recognise the need to improve conditions in the countries of origin so people do not feel the need to migrate.

Progress in this respect is painfully slow because of opposition to aid programmes in the US Congress, but Mexico has set the example with its own aid.

Organised crime and narcotics are also ongoing problems, but here too Mexico has taken effective measures to combat illegal trafficking, including of fentanyl, which in any case is produced and commercialised much more within the US.

Amlo regularly denounces and ridicules hysterical calls from US politicians (Republicans and even a few Democrats) for armed intervention against drug cartels: he rightly points out that this is cheap politicking, and the US is incapable of invading Mexico which would be catastrophic for its own interests.

A crucial point totally ignored by the media is that on September 8-9 Amlo, who rarely travels outside Mexico, was in Cali, Colombia as guest of honour in a Latin American conference on drugs, welfare and migration hosted by President Gustavo Petro.

They agreed that the “war on drugs” was a total failure and that as a matter of urgency, they must collaborate to replace military action with the promotion of popular welfare and a productive rural economy to combat crime and limit migration.

Amlo then continued to Chile where he was also guest of honour in the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the coup and the tribute to the memory of Salvador Allende.

One of Mexico’s flagship social programmes is Sembrando Vida, “sowing life,” an agroforestry scheme which combines sowing fruit and timber trees with traditional farming; financial support and technical training enables peasants in communities to earn a living while reforesting and improving the land.

In Mexico, it has reforested over a million hectares and benefited 440,000 farmers, and with generous Mexican aid has also benefited tens of thousands in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Belize. Colombia is now promoting Sembrando Vida as part of its own agrarian reform to bring justice and hope to the rural poor.

Amlo and Foreign Secretary Alicia Barcena have been active in support of the left government of Xiomara Castro in Honduras (constantly threatened with destabilisation by local and transnational mining interests) and now for the democratic president-elect of Guatemala, Bernardo Arevalo, the first progressive leader of that much-abused country in nearly 70 years (since the 1954 CIA coup).

As political manoeuvres continue with a view to next year’s elections, the growing prominence of women is remarkable. Those wanting to stand for office had to resign from their existing posts, so the male occupants of the key positions of Home Secretary and Foreign Secretary both stood down to seek nomination for the presidency, but neither was successful, losing out to Sheinbaum.

Those replacing them are very capable and promising women: the young and very capable Luisa Alcalde as Home Secretary and Alicia Barcena as Foreign Secretary. They may not hold these positions in the new cabinet in a year’s time, but their impact in a short space of time suggests that they have a promising future.

Candidates for other important positions include Clara Brugada for metro mayor of Mexico City. Brugada was mayor of the capital’s largest borough, Iztapalapa, having emerged as a grassroots activist 40 years ago and now a respected figure on the left; I met her 18 months ago and she has pioneered popular welfare with her “Utopias” community centre programme.

Amlo’s opponents can find little of substance to criticise except by accusing him of “militarising” the country. He has indeed surprised many by working closely with the Armed Forces, but this may well be one of his most effective strategic moves.

What he has done is to imbue the military with a sense of their historic roots in revolutionary popular insurgency, and a sense of national cultural identity: the officer corps is not recruited as an elite caste, unlike Chile, Argentina or Colombia.

Moreover, they are not given political roles: the only officers in the cabinet are the defence and navy secretaries, and there are no military state governors or members of congress.

What then to do with a disciplined armed force with a hierarchical command structure? Use it to combat organised crime, but also for public works and to assist in welfare programmes in cooperation with communities. As a result, they are very popular with working people who appreciate their competence and professionalism.

David Raby is a retired academic and co-ordinator of the Mexico Solidarity Forum. Follow him on X @DLRaby.