This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

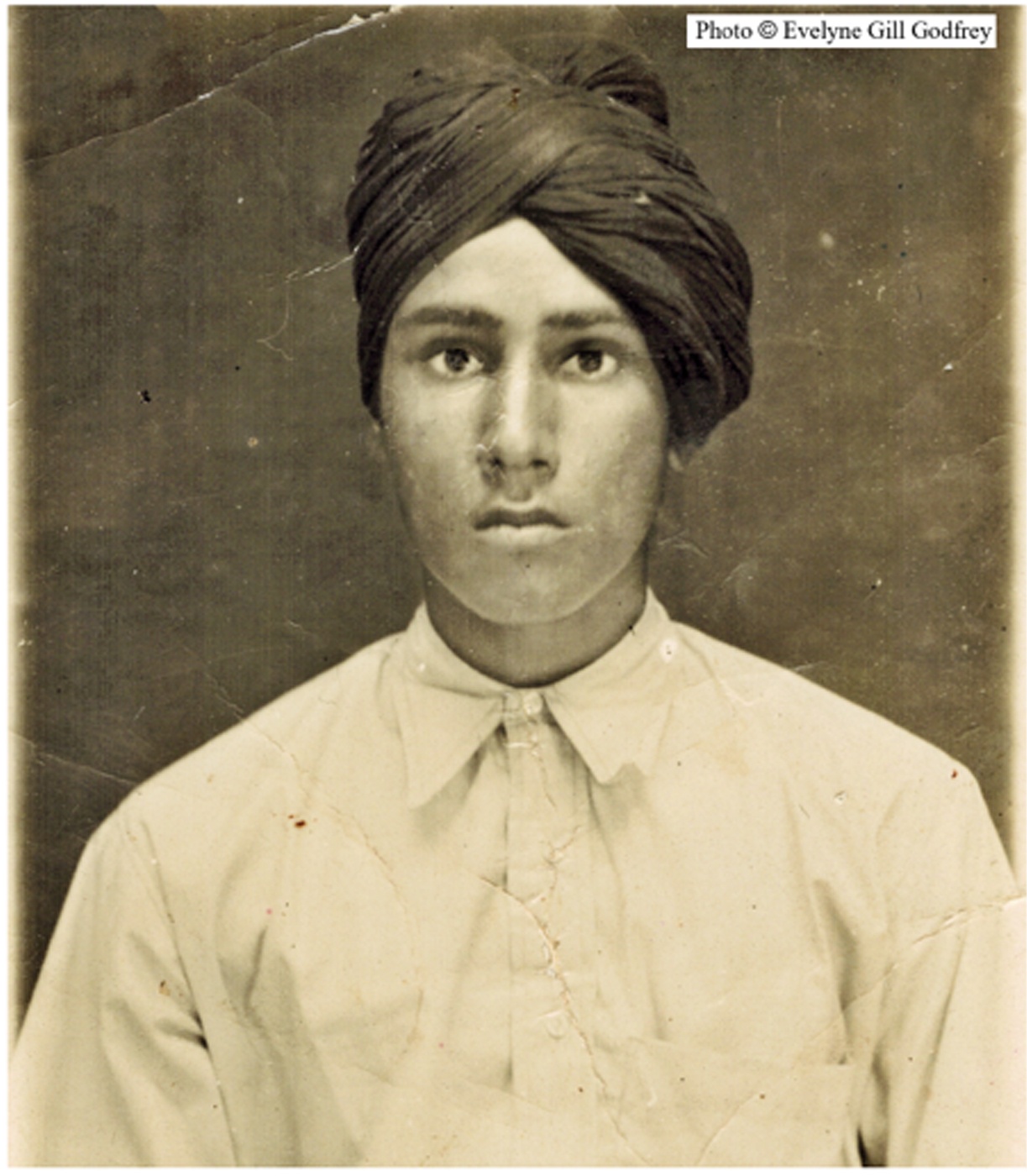

THE first photo I have of my grandfather was presumably taken by the British colonial authorities in the Punjab, after his arrest for protesting against the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre at Amritsar.

At the time of the massacre in April 1919, my great-uncle had just returned to their farm in the village of Posi, a district of Hoshiarpur in the Punjab, after serving in the British Army’s Sikh Regiment in the first world war.

My grandfather went with his older brother to protest against the Amritsar massacre. Along with thousands of others, they were both arrested. My great-uncle was eventually released after serving two years in prison.

My grandfather was an activist involved in the Indian independence movement from 1919-47, most of that time as a member of the Indian Independence League. My grandmother read law in the early 1930s, when very few women went to university at all.

My grandfather spoke out for the equality of women, and was against arranged marriage, as women were essentially treated as “chattels.” He recognised that women were not just considered socially and economically inferior, but also subjugated on religious grounds.

Even before the catastrophic loss of life during the partition of India in 1947, my grandfather had come to see how religion is a purely personal matter that, when transferred to the public domain, can become grounds for irrational hatred and conflict, rather than any sort of force for peace.

My grandmother, meanwhile, like hundreds of millions of Asians (and Africans, and indigenous North and South Americans), was a devout Christian. Her family had been Catholic for 400 years. That, as well as the fact that English was her first language, was a consequence of colonialism.

English is still one of India’s official languages today, and Christianity is the third-largest religion, after Hinduism and Islam. There are more Christians than Sikhs in India. Although all my other Indian relatives are Sikh, my grandfather converted to Christianity in order to marry my grandmother in a church.

The British colonial authorities’ brutal response to the protests after the 1919 massacre pushed thousands of young men like my grandfather to become activists committed to fighting for Indian independence.

Protesters were detained under emergency powers (the notorious Rowlatt Acts) that had been extended after WWI. So-called “seditionists” could be held for up to two years in prison without being charged, but on the understanding they had committed treason. Treason was of course a hanging offence, for which the minimum age was 16.

My grandfather was one of the teenagers who were to be kept in prison until old enough to hang. However, the British colonial authorities arrested so many people between in 1919-22, that they could not build prisons fast enough. In the ensuing chaos, my grandfather escaped.

On the run and with no qualifications, my grandfather did the most expedient thing to survive: he lied about both his age and his name, and joined the very army that had opened fire on the innocent civilians at Jallianwala Bagh.

He served as “Driver Singh” in the Army Service Corps and was sent off to fight in the campaign in Mesopotamia that carried on into the 1920s in Iraq and Iran, or as my grandfather always called it, Persia.

“When I was your age, I was driving trucks in the Persian Army!” he’d say if ever we tried to avoid any inconvenient task. I knew it couldn’t be literally true (when I was, for example, seven years old), but that’s the perspective from which I saw things as a child: however much I hate homework or brushing my teeth, what’s worse is to be cannon fodder in a foreign war.

The next photo I have of my grandfather was taken in Singapore around 1924. There he met up with other Indian “seditionists” in exile and joined the recently formed Indian Independence League. In the late 1920s, he moved out of British jurisdiction to Manila, which was at the time effectively under US colonial control.

What you can see in this photo of nearly 100 years ago, is a young man who doesn’t play the imperialist game of “identity politics.” He clearly wanted to be respected as an individual and as an equal to any white man, not seen as a representative of some foreign breed, creed, class or culture.

A few years later, he would blag his way into university, but at the time of this photo — that you’d think was a portrait of an Oxford undergraduate or ex-public school boy — his formal education was limited to what had been available back in the village.

It is shared cultural characteristics such as language and religion that, in combination, define an ethnic minority group. My mother and grandparents spoke Britain’s majority language and belonged to the majority religion. But they still faced racist discrimination.

According to the identity politics that prevail today, people who aren’t white are seen not as individuals, but instead are “representative” of everyone else who looks like them.

The legacy of empire that we still have to confront today is that people with Asian or African ancestry are categorised according to foreign “ethnicity,” and the racist implication is that they are not really or fully British.

Dr Evelyne Godfrey is an archaeologist and a director of Oxford City of Sanctuary.