This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE notion that someone facing a terminal illness or fatal condition should be able to decide at what point their life should be brought to a close, and to opt for “death with dignity,” isn’t one that can be brushed aside.

Many of us will find ourselves or someone we love in a situation where such a decision is anything but an abstract consideration.

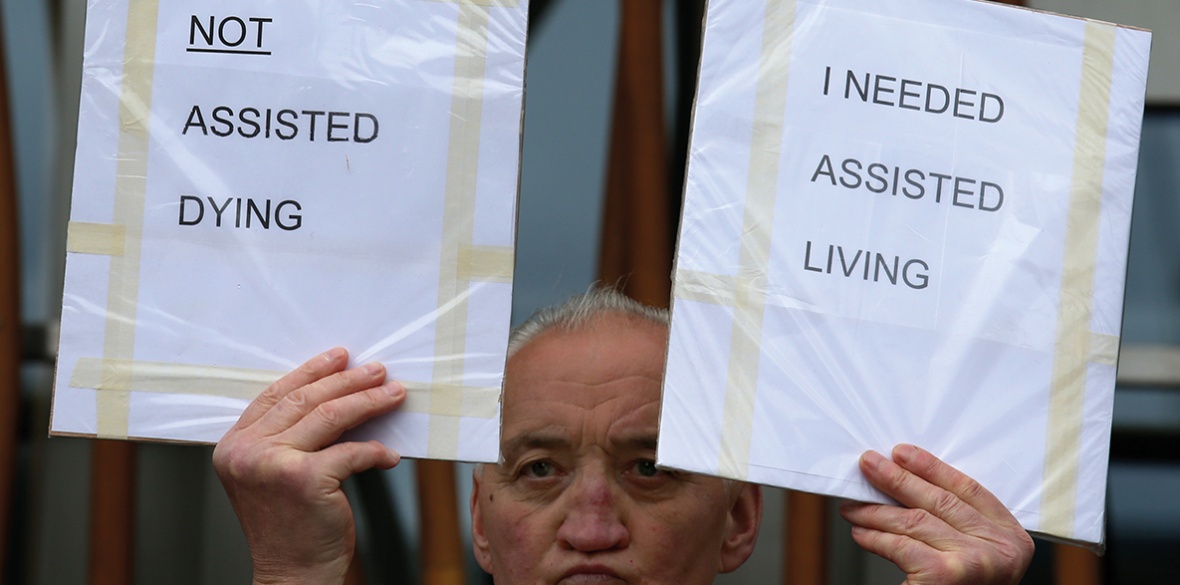

Yet the reality is that no public policy can be considered outside of the broader social and political context. As austerity measures take ever-greater effect and the provision of healthcare and vital support services are effectively rationed, the danger is that assisted dying can be effectively forced on those who have been socially abandoned.

Moreover, when this intersects with deeply entrenched notions of a hierarchy in the value of life, the risks become even greater and a humane measure can be horribly warped into something dreadful.

In Canada, this dilemma is being posed in the very sharpest terms. In the spring of last year, the country’s system of medical assistance in dying (Maid) was expanded so as to become available to those “whose natural death is not reasonably foreseeable.”

At the time, disability rights advocates argued that “due to racism and ableism, expanding Maid will simply lead to more people with disabilities ending their lives.”

As Sara Jama of the Disability Justice Network of Ontario put it, “It looks as though the government is rushing legislation to allow people the right to die without also supporting the right to live, and that’s where I get worried.”

Plans now in effect to expand Maid to those with mental health diagnoses add a new element of danger to those words.

In 2021, there was a 32.4 per cent increase in those whose lives were ended by Maid and 2.2 per cent of these (219 individuals) were in the “natural death is not reasonably foreseeable” category.

It can’t be credibly denied that this represents “far too much death among individuals who couldn’t live fulfilling lives because of a lack of support for dealing with their disability/disabilities.”

Last month, it was reported that Amir Farsoud, who suffers from chronic pain, depression and anxiety as a result of an injury, and who lives in St Catharines, Ontario, “is in the process of applying for medical assistance in dying (Maid), not because he wants to die, but because social supports are failing him and he fears he may have no other choice.”

Farsoud is, clearly and indisputably, being driven to end his life because of what can only be described as social abandonment.

He lives on sub-poverty social benefits and, with the home he shares with others now up for sale, he simply can’t find housing he can afford.

“I don’t want to die but I don’t want to be homeless more than I don’t want to die,” he stated.

This case adds weight to a warning contained in a 2021 UN report that when “life-ending interventions are normalised for people who are not terminally ill or suffering at the end of their lives, such legislative provisions tend to rest on — or draw strength from — ableist assumptions about the inherent ‘quality of life’ or ‘worth’ of the life of a person with a disability.”

Earlier in the year, the situation came to light of Denise, a 31-year-old woman in Toronto who uses a wheelchair and who was seeking Maid because she couldn’t find affordable housing.

As she put it starkly, “I’ve applied for Maid essentially … because of abject poverty.” Denise had multiple chemical sensitivities (MCS) and needed a home that was wheelchair accessible and that had cleaner air.

The lack of these basic supports led this young woman to declare that she was “relieved and elated” that her application for Maid was moving forward.

She had even asked the doctors working with her to waive the normal 90-day waiting period for those whose natural death is imminent so that her life could be brought to a close even sooner.

Though there was ample evidence that the quality of Denise’s life could be greatly improved simply by finding a home where the air was less likely to trigger her allergies, “none of the doctors [involved in her Maid application] contacted her to learn about the efforts to help Denise find housing first.”

David Lepofsky, a disability advocate, observed that “we’ve now gone on to basically solving the deficiencies in our social safety net through this horrific back door, not that anybody meant it that way, but that’s what it’s turned into.”

Hundreds of thousands of people in Canada suffer from sensitivities to chemicals and Dr Riina Bray, medical director of the environmental health clinic at Women's College Hospital in Toronto, suggests that “society is failing these patients. My hope is that we can just put a stop to this very easy out that Maid is providing and start acknowledging that these people need to be helped.”

In 2017, Statistics Canada found that “nearly a quarter of disabled people are living in poverty. That’s roughly 1.5 million people, or a city about the population of Montreal.”

Clearly, the implications of a system of medically assisted death that reinforces an agenda of austerity and abandonment are dire. In the present context of a deepening cost of living crisis, this becomes utterly horrifying.

Healthcare systems in Canada are under severe pressure and had been deteriorating long before the dreadful impact of the pandemic compounded the problem massively.

As waiting times for medical procedures grow and the capacity to provide timely emergency treatment is compromised, the threat of the misuse of assisted dying increases.

In 2020, an article appeared in the British Medical Journal that was entitled “Are intensive care protocols harming the disabled?”

In the context of surging Covid caseloads, it examined “exclusion criteria [that] dictate who will not be considered when providing access to advanced care and treatment” in various countries.

The article noted that “numerous US states, including Tennessee, exclude individuals with developmental disabilities and the life-limiting illnesses.”

It pointed to cases in Britain of “patients being designated ‘do not resuscitate’ (DNR) without consultation with the patient or their families.”

It also drew attention to “drafted guidelines for the province of Ontario in Canada [that] also excluded specific disabilities and individuals who require assistance and accommodation.”

The UN special rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities, Catalina Devandas, suggests: “Current developments in medical research and practice may revive eugenic ideas if safeguards for those affected are not ensured.”

It is hardly an alarmist overreaction to suggest that such “safeguards” are lacking in the implementation of Maid in Canada.

The website of Dying With Dignity Canada declares: “It’s your life. It’s your choice” and there is much to agree with in that proposition.

However, there is no freedom of choice for those who are driven to end their lives because of poverty and exclusion.

Reactionary decisions about which lives are valuable and which are expendable simply rob the end of life decision-making process of any validity.

This article first appeared at www.counterfire.org.