This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IT IS difficult to overstate the grip of Covid-19 on India.

WhatsApp bristles with messages about this or that friend and family member with the virus, while there are angry posts about how the central government has utterly failed its citizenry.

This hospital is running out of beds and that hospital has no more oxygen, while there is evasion from Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his cabinet.

Thirteen months after the World Health Organisation (WHO) announced that the world was in the midst of a pandemic, the Indian government looks into the headlights like a transfixed animal, unable to move.

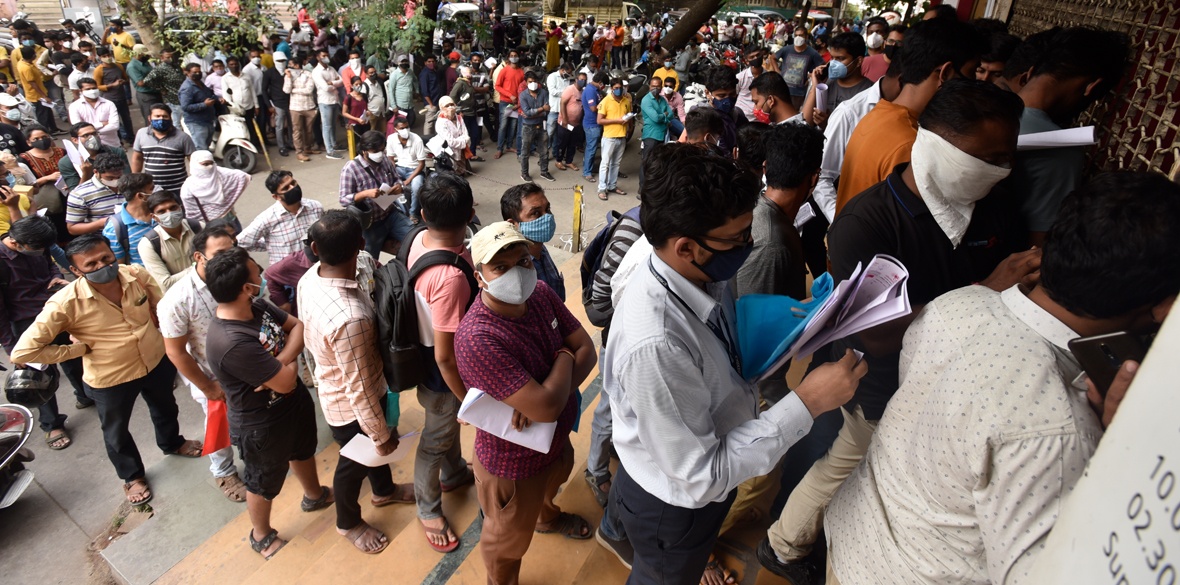

While other countries are well advanced in their vaccination programmes, the Indian government sits back and watches a second wave or a third wave land heavily on the Indian people.

On Monday May 3 2021, the country registered more than 400,000 cases in a 24-hour period, the tenth day in a row of record-setting highs.

Bear in mind that in China, where the virus was first detected in late 2019, the total number of detected cases stands at less than 100,000.

This spike in India has raised eyebrows: is this a new variant, or is this a result of failure to manage social interactions (including the three million pilgrims who gathered at this year’s Kumbh Mela religious festival) and to vaccinate enough people?

At the core is the total failure of the Indian government, led by Modi, to take this pandemic seriously.

A glance around the world shows those governments that disregarded the WHO warnings suffered the worst ravages of Covid-19.

From January 2020, the WHO had asked governments to insist on basic hygiene rules — washing hands, physical distance, mask-wearing — and then later had suggested testing for Covid-19, contact tracing and social isolation.

The first set of recommendations do not require immense resources. Vietnam’s government, for instance, took those recommendations very seriously and slowed the spread of the disease immediately.

India’s government moved slowly, despite evidence of the dangerousness of the disease. By March 10, 2020, before the WHO declared a pandemic, the Indian government reported about 50 Covid-19 cases in India, with infections doubled in 14 days.

The first major act from India’s prime minister was a 14-hour curfew, which was dramatic but not in line with the WHO recommendations.

This ruthless lockdown, with four hours’ notice, sent hundreds of thousands of workers on the road to their homes, penniless, some dying by the wayside, many carrying the virus to their towns and villages.

Modi executed this lockdown without checking with his own departments, whose advice might have warned him against such a precipitous and unnecessary act.

Modi took the entire pandemic lightly. He urged people to light candles and bang pots, to make noise to scare away the virus. The lockdown kept being extended, but there was nothing systematic, no national policy that one can find anywhere on the government’s websites.

In May and June of 2020, the lockdown kept getting extended, although this was meaningless to the millions of working-class Indians who had to go to work to survive on their daily wages.

A year into the pandemic, there are now over million people in India with detected infections, with ,000 people confirmed dead from the pandemic.

One has to write words like “detected” and “confirmed” because mortality data from India during this pandemic has been totally unreliable.

The consequences of turning over healthcare to the private sector and underfunding public health have been diabolical.

For years now, advocates of public healthcare, such as the “people’s health movement” Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, have called for more government spending on public health and less reliance upon profit-driven healthcare. These calls fell on deaf ears.

India’s governments have spent very low amounts on health — 3.5 per cent of GDP in 2018, a figure that has remained the same for decades.

India’s current health expenditure per capita, by purchasing power parity, was 275.13 in 2018 — around the figures of Kiribati, Myanmar and Sierra Leone.

This is a very low number for a country with the kind of industrial capacity and wealth of India.

In late 2020, the Indian government admitted that it has 0.8 medical doctors for every 1,000 people and it has 1.7 nurses for every 1,000 people. No country of India’s size and wealth has such low ratios of medical staff.

It gets worse. India has only 5.3 beds for every 10,000 people, while China, for example, has 43.1 beds for the same number.

India has only 2.3 critical care beds for 100,000 people (compared with 3.6 in China), and it has only 48,000 ventilators (China had 70,000 ventilators in Wuhan alone).

The weakness of medical infrastructure is wholly due to privatisation, where private-sector hospitals run their system on the principle of maximum capacity and have no ability to handle peak loads.

The theory of optimisation does not permit the system to tackle surges, since in normal times it would mean that the hospitals would have surplus capacity.

No private sector is going to voluntarily develop any surplus beds or surplus ventilators. It is this that inevitably causes the crisis in a pandemic.

Low health spending means low expenditure on medical infrastructure and low wages for medical workers. This is a poor way to run a modern society.

Shortages are a normal problem in any society. But the shortages of basic medical goods in India during the pandemic have been scandalous.

India has long been known as the “pharmacy of the world,” since its pharmaceutical industry sector has been proficient at reverse-engineering a range of generic drugs. It is the third-largest pharmaceutical industry manufacturer.

India accounts for 60 per cent of global vaccine production, including 90 per cent of the WHO use of measles vaccine, and India has become the largest producer of pills for the US market. But none of this helped during the crisis.

Vaccines for Covid-19 are not available for Indians at the pace necessary. Vaccinations of Indians will not be completed before November 2022.

The government’s new policy will allow vaccine-makers to hike up prices, but not produce fast enough to cover needs (India’s public-sector vaccine factories are sitting idle).

No large-scale rapid procurement is on the cards. Nor is there enough medical oxygen and promises to build capacity have been unfulfilled by the ruling party.

India’s government has been exporting oxygen, even when it became clear that domestic reserves were depleted (it has also exported precious Remdesivir injections).

On March 25 2020, Modi said that he would win this Mahabharat — the 18-day-long battle described in India’s epic legend — against Covid-19 in 18 days.

Now, more than 56 weeks after that promise, India looks more like the blood-soaked fields of Kurukshetra (1,66 million are said to have died in that battle), where thousands lay dead, with the war not even at midpoint.

This article appeared at peoples-world.org. Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor, and journalist. His latest book is Washington Bullets (Monthly Review Press).