This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE Cultural Revolution started in 1966 as a mass movement of university and school students, incited and encouraged by Mao and others on the left of the CPC leadership.

Student groups formed in Beijing calling themselves Red Guards and taking up Mao’s call to “thoroughly criticise and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois ideas in the sphere of academic work, education, journalism, literature and art.”

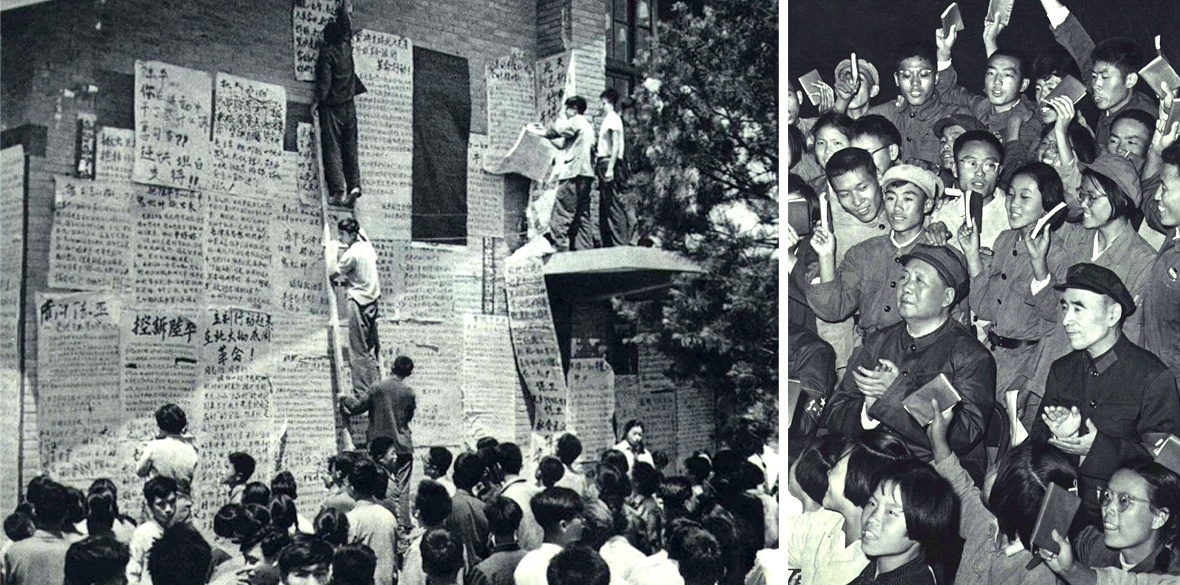

The students produced “big-character posters” (dazibao) setting out their analysis against, and making their demands of, anti-revolutionary bourgeois elements in authority.

Mao produced his own dazibao calling on the revolutionary masses to “Bombard the Headquarters” — that is, to rise up against the reformers and bourgeois elements in the party.

These developments were synthesised by the CPC central committee, which in August 1966 adopted its Decision Concerning the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution: “Our objective is to struggle against and overthrow those persons in authority who are taking the capitalist road; to criticise and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois academic ‘authorities’ and the ideology of the bourgeoisie and all other exploiting classes and to transform education, literature and art and all other parts of the superstructure not in correspondence with the socialist economic base, so as to facilitate the consolidation and development of the socialist system.”

Thus the aims of the Cultural Revolution were to stimulate a mass struggle against the supposedly revisionist and capitalist restorationist elements in the party; to put a stop to the hegemony of bourgeois ideas in the realms of education and culture; and to entrench a new culture — socialist, collectivist, modern.

This mass movement, only partially under the control of the party, quickly became chaotic. Universities were closed. Red Guards occupied and ransacked the Foreign Ministry.

Han Suyin describes the atmosphere of the early days of the Cultural Revolution: “Extensive democracy. Great criticism. Wall posters everywhere. Absolute freedom to travel. Freedom to form revolutionary exchanges. These were the rights and freedoms given to the Red Guards, and no wonder it went to their heads and very soon became total licence.”

There was no small amount of violence. Many of those accused by the Cultural Revolution Group (CRG) suffered horrible fates.

Posters appeared with the slogan “Down with Liu Shaoqi! Down with Deng Xiaoping! Hold high the great red banner of Mao Zedong thought.”

Liu’s books were burned in Tiananmen Square. He was expelled from all positions and arrested, interrogated, confined to an unheated cell, and denied medical care. He died under house arrest in 1969.

Peng Dehuai, former Defence Minister and the leader of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army’s operations in the Korean War, had been forced into retirement in 1959 after criticising the Great Leap Forward.

Jiang Qing – Mao’s wife, and a leading figure in the CRG – sent Red Guards to arrest him. He was repeatedly beaten and interrogated, and died in a prison hospital in 1974.

Although Mao had only intended it to last for a few months, the Cultural Revolution only came to its conclusion shortly before Mao’s death in 1976, albeit with varying intensity — realising that the situation was getting out of control, in 1967 Mao called on the army to help establish order and reorganise production. However, the situation flared up again with the ascendancy of the “Gang of Four” from 1972.

Historians in the capitalist countries tend to present the Cultural Revolution in the most facile and vacuous terms. To them, it was simply the quintessential example of Mao’s obsessive love of violence and power; just another episode in the long story of communist authoritarianism. But psychopathology is rarely the principal driving force of history.

In reality, the Cultural Revolution was a radical mass movement. Millions of young people were inspired by the idea of moving faster towards socialism, of putting an end to feudal traditions, of creating a more egalitarian society, of fighting bureaucracy, of preventing the emergence of a capitalist class, of empowering workers and peasants, of making their contribution to a global socialist revolution, of building a proud socialist culture unfettered by thousands of years of Confucian tradition. They wanted a fast track to a socialist future. They were inspired by Mao and his allies, who were in turn inspired by them.

Such a movement can get out of control easily enough, and it did. Mao can’t be considered culpable for every excess, every act of violence, every absurd statement (indeed he intervened at several points to rein it in), but he was broadly supportive of the movement and ultimately did the most to further its aims.

Mao had enormous personal influence – not solely powers granted by the party or state constitutions, but an authority that came from being the chief architect of a revolutionary process that had transformed hundreds of millions of people’s lives for the better. He was as Lenin was to the Soviet people, as Fidel Castro remains to the Cuban people. Even when he made mistakes, these mistakes were liable to be embraced by millions of people.

The Cultural Revolution is now widely understood in China to have been misguided. The political assumptions of the movement — that the party was becoming dominated by counter-revolutionaries and capitalist-roaders; that the capitalist-roaders in the party would have to be overthrown by the masses; that continuous revolution would be required in order to stay on the road to socialism — were explicitly rejected by the post-Mao leadership of the CPC, which pointed out that “the ‘capitalist-roaders’ overthrown … were leading cadres of party and government organisations at all levels, who formed the core force of the socialist cause.”

The turmoil of the Cultural Revolution impeded the country’s development and brought awful tragedy to a significant number of people. What so many historians operating in a capitalist framework fail to understand is why, in spite of the chaos and violence of the Cultural Revolution, Mao is still revered in China. For the Chinese people, the bottom line is that his errors were “the errors of a great proletarian revolutionary.”

It was the CPC, led by Mao and on the basis of a political strategy principally devised by him, that China was liberated from foreign rule; that the country was unified; that feudalism was dismantled; that land was distributed to the peasants; that the country was industrialised; that a path to women’s liberation was forged.

The excesses and errors associated with the last years of Mao’s life have to contextualised within this overall picture of unprecedented, transformative progress.

The pre-revolution literacy rate in China was less than 20 percent. By the time Mao died, it was around 93 percent. China’s population had remained stagnant between 400 and 500 million for a hundred years or so up to 1949. By the time Mao died, it had reached 900 million. A thriving culture of literature, music, theatre and art grew up that was accessible to the masses of the people. Land was irrigated. Famine became a thing of the past. Universal healthcare was established. China – after a century of foreign domination – maintained its sovereignty and developed the means to defend itself from imperialist attack.

Hence the “Mao as monster” narrative has little resonance in China. As Deng Xiaoping himself put it, “without Mao’s outstanding leadership, the Chinese revolution would still not have triumphed even today. In that case, the people of all our nationalities would still be suffering under the reactionary rule of imperialism, feudalism and bureaucrat-capitalism.”

Furthermore, even the mistakes were not the product of the deranged imagination of a tyrant but, rather, creative attempts to respond to an incredibly complex and evolving set of circumstances. They were errors carried out in the cause of exploring a path to socialism – a historically novel process inevitably involving risk and experimentation.