This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

FIRST mentioned by Mao Zedong in 1953 in China’s transition to socialism, the phrase “common prosperity” was also used by Deng Xiaoping — his call for some to “get rich first” always qualified with the phrase “so that they can help others to catch up.”

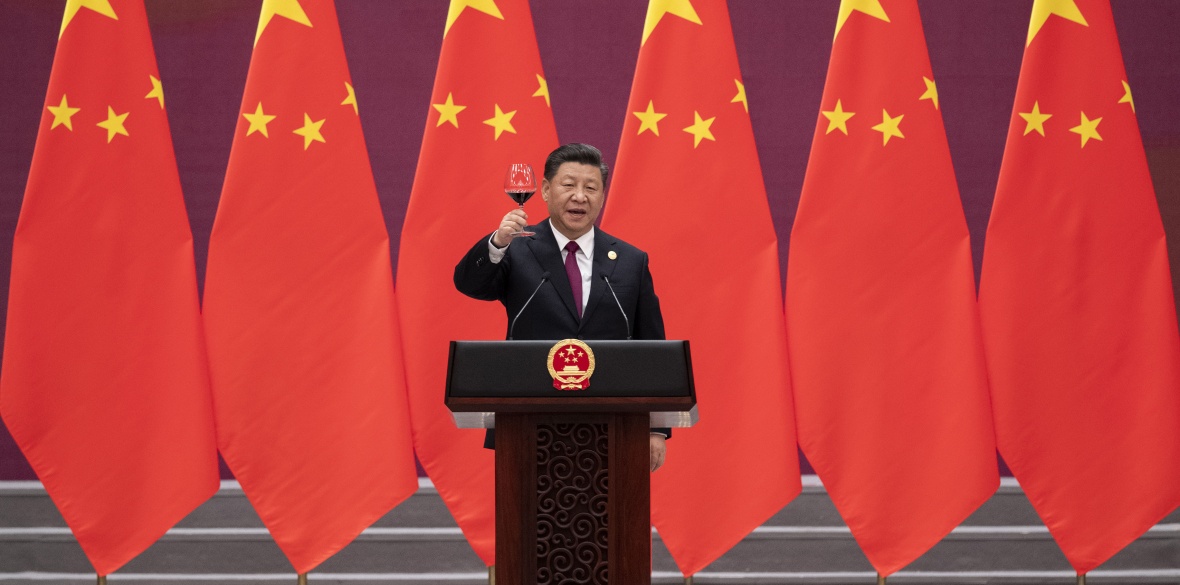

Now Xi is taking “common prosperity” as a defining feature of China’s socialist modernisation — at the core of the two-stage plan, laying a basic socialist foundation by 2035 to then advance to modern socialism by 2049, the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

The gap between rich and poor is to be reduced, but what common prosperity is not is an equalisation of incomes or a radical redistribution from the rich to the poor. Xi talks rather of increasing the incomes of low-income earners and expanding the size of the middle-income group.

Incomes and inequalities

China’s income per capita had by 2021 reached around $12,000, the World Bank borderline between an upper-middle and high-income country.

Along this route to “moderate prosperity,” as China built cities, encouraged private enterprise, and developed share ownership and the property market, inequalities grew — numbers of super-rich tycoons emerged together with the rise of a middle-income group of some 400 million, most owning their own homes, spending on luxuries, and some travelling overseas and sending their children to the country’s fast-developing universities.

The worst of China’s poverty has been eradicated, but an estimated 600 million still live on less than $5 a day. The more vociferous, burgeoning middle class has been the focus of government attention — but what about the low pay and poor working conditions of the 300 million rural migrants? What about the 500 million or so left in the rural areas, some still scraping a living on small plots of land?

The priorities

Inequality is structured into China in the urban-rural gap and uneven and regional development. In the coming years, continued migration to the cities will clear the way for agricultural modernisation, raising the remaining farmers’ incomes.

But common prosperity is also about shifting from catering to middle-class demands to improving the rights and interests of the workers.

Low pay and poor conditions continue to plague the private sector in particular. Including household and micro-enterprises, this accounts for some 80 per cent of urban employment. Not before time, tougher regulations have been introduced in the food delivery sector — minimum income guarantees, relaxation of delivery deadlines, ensuring social insurance coverage — while the infamous “996” pattern of working from 9am until 9pm six days per week, common among technology firms, has been ruled illegal.

China’s labour laws are rated highly by international standards but implementation is very uneven. A recent BBC programme about Shein fashion, whose founder Chris Xu is now a tycoon, exposed quite appalling practices of excessive overtime and docking of pay for substandard work.

These practices may not be typical, but certainly do occur. They are against the law, as the programme pointed out — but in China, where business has expanded so rapidly over the last 20 or 30 years through personal contacts, although practices have greatly improved, individual influence can still trump the law.

Xi is now calling for improvements in labour laws and greater provision of legal advisory agencies to address the problems; collective bargaining — independent worker representatives are elected from the shop floor in the car industry for example — may also start to play more of a part. However, urgent though these improvements are, a radical readjustment in the relations between capital and labour in the private sector would cause economic disruption and will be approached with caution.

Common prosperity also covers more equitable access to improved public services. However, while the role of taxation and social security is to be enhanced, the central thrust of the agenda is seen to lie in creating higher-quality, better-paid jobs. And the route forward for China’s 800 million-strong workforce is through education.

Invigorating China through science and education

China’s immediate priority is to upgrade its technology. Escaping the dead end of trading cheap labour exports for high-end imports means pouring investment into skills and science, innovating new technologies to drive the industrialisation of the future.

This has become a matter of survival, as US decoupling aims to lock China into a trap where, no longer offering cheap labour at the lowest ends of the supply chain, it remains unable to compete at the top end.

With Xi now throwing the state into gear to engineer the modernising breakthroughs, Western naysayers proclaim China’s bureaucratism can only suffocate new ideas and strangle innovation in red tape: only capitalism, apparently, can incentivise creativity.

But the Chinese system has its advantages, as Xi focuses resources on developing its own first-class scientists, highly skilled engineers and innovation teams.

A network of national laboratories and research centres is complemented by flexible arrangements combining state and private enterprise. “Guidance funds” offered by local governments to start-ups look to boost R&D and train talent. A system of state shares in private companies can be co-ordinated to foster clusters and to fill in the supply chain around core state enterprises at local levels.

Secondly, as Huawei has demonstrated, employee share ownership can be an effective way of stimulating motivation and loyalty. “Technology shares” are a practice used to tie in valued specialists and skilled personnel.

It is often in the actual process of production that new techniques are worked out. And here China has its own pre-modern practices of invention and learning by doing as renowned Sinologist Joseph Needham detailed in his series Science and Civilisation in China.

These traditions appear to be paying off now as China takes the lead, with nearly one-third of the world’s renewable energy patents.

Indeed, decarbonisation is seen to be the route to high-quality development with climate change leveraging change across China’s entire social and economic structure.

Zhejiang paves the way

Xi has set the goal of doubling the middle-income group to 800 million by 2035. Zhejiang province, designated the “common prosperity demonstration zone,” is to pioneer the future. The middle-income category — those between $14,000 and $70,000 — is to expand to 82 per cent of its population by 2025, above that of Germany and the US.

The enrolment rate in tertiary education is to rise to more than 70 per cent and “public service centres” are to be provided for urban residents with facilities offering preschool education, health and senior care, and physical exercise within 15 minutes walking distance. Life expectancy is to be lifted above the national average of 77 to over 80 years.

But Xi will be sailing into the headwinds in the short term with the property market in difficulties and continuing challenges in dealing with Covid.

China’s idea of its socialist future may not be what some on the Western left have in mind: while the goal is to regulate excessively high incomes, the private sector will continue to grow, China will still have its tycoons and will still make great efforts to attract foreign investment — but if it does succeed in containing the “disorderly growth of capitalism” in such a way as to achieve, even approximately, the Zhejiang targets across the whole of China within the next three decades this surely would be to achieve something remarkable.