This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THERE IS a Caribbean saying that could sum up the life and trailblazing work of Claudia Jones: making a way out of no way.

Scholars have interpreted the proverb as a rallying cry for resilience and creativity. There’s a feminist take on it, too, which celebrates women who have crafted lives of great meaning from limited opportunities.

This was one theme of Jones’s life, though there were many, all to be found in the new book from David Horsley, The Political Life and Times of Claudia Jones.

Speaking at the online book launch recently, Horsley, author, historian and stalwart of the Communist Party of Britain, reminded the audience that “the British state put her image on a stamp, as a civil rights activist.”

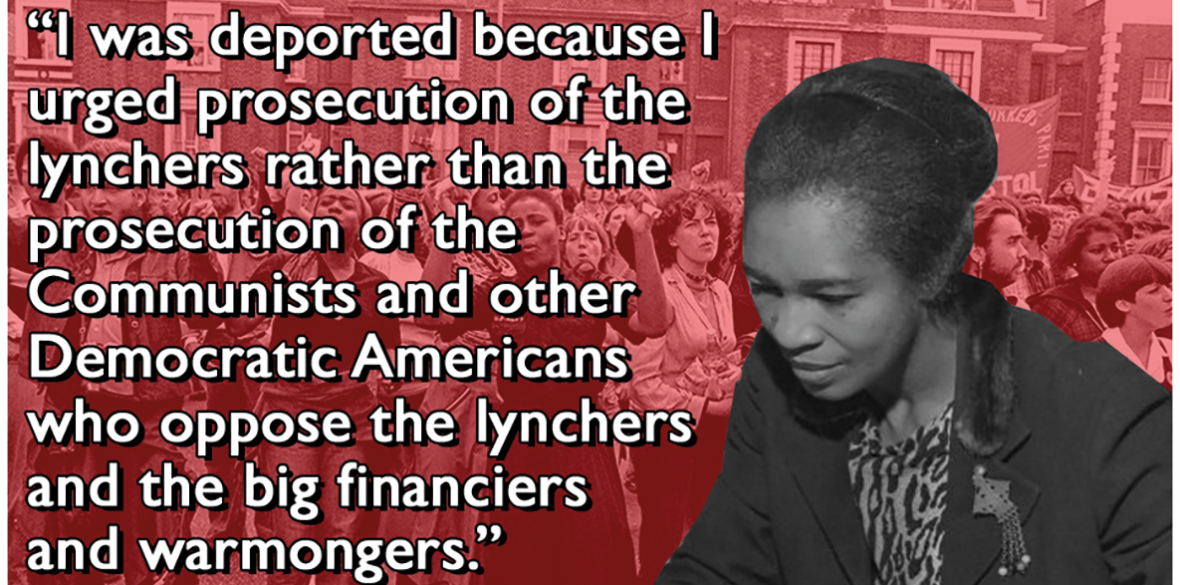

But she was much more, he said, a feminist, journalist, fighter against imperialism and colonialism — “and above all, a communist.”

A member of the American party from 1936, until her deportation in 1955, Jones joined the party in Britain that year and remained a member until her premature death in 1964.

When her family moved from Trinidad to New York, they were full of optimism, said Horsley, “but the dream was soon disabused.”

They were poor and suffered “the scourge of indignity stemming from Jim Crow oppression,” as the vile laws enabling racial discrimination were not ditched until 1965.

“Her mother died aged 37 and Claudia started to understand the sufferings of her people and her class. She listened to street corner meetings in Harlem and was impressed by the communist speakers.”

When US communists championed the case of the Scottsboro Boys, in which black teenagers were falsely accused of rape, Jones joined the Young Communist League.

As a writer for the Daily Worker and later editor of several publications, Jones started to raise the issue of “triple oppression,” affecting black, working-class women. It was, she argued, a barometer of the status of all women.

Jones cited as her mentors several communist women, including activist Louise Thompson Patterson, who travelled to Spain during the civil war, founded a Harlem chapter of the Friends of the Soviet Union and the Harlem Suitcase Theatre.

Jones, in turn, mentored civil rights activist Charlene Mitchell, now aged 90, who went on to mentor Angela Davis, having spearheaded the campaign to free her.

The pattern of women “making a way out of no way” was firmly established. It was a sensibility that Jones brought to Brian, when the US deported her.

Working alongside fellow communists Trevor Carter [her cousin] and Billy Strachan [also the subject of a book by Horsley], she fought for an end to discrimination against black workers.

She rallied for repeal of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, widely seen as a racist betrayal of citizens who had left their countries of birth to work in Britain.

Lawyer Jacqueline McKenzie, who has represented more than 200 victims of the current Windrush scandal, said: “They felt they were moving from one part of the Commonwealth to another!

“We need to look at the ideologies of governments when it comes to deportation — at all governments. And we should remember that 11 Labour MPs wrote to prime minister Clement Attlee [on June 22 1948] urging him to stop the Empire Windrush from docking.”

In a week which saw a number of Jamaican-born people deported from Britain, McKenzie said we needed an activist of Jones’s status now.

“We don’t see that sort of person now — where is today’s Claudia Jones?”

Firmly in agreement was author and activist Angela Cobbinah, who read a statement from veteran Winston Pinder, contemporary of Jones and part of the delegation to meet her on her arrival in London in 1955.

Pinder said: “I had the privilege of getting to know her better. Claudia was a truly remarkable person. I regard her as my political mentor.”

Cobbinah, who has recently argued for a statue of Jones, was part of the fundraising campaign, alongside Pinder, in 1982. They wanted a stone for Jones’s unmarked grave, next to that of Karl Marx in Highgate Cemetery.

Her first encounter with Jones’s legacy was in a squatters’ campaign for a hostel in Camden.

“We’d all heard about Claudia. Billy [Strachan] told us and we were always thrilled to hear about her. It seemed awful that her grave had had nothing to mark it for nearly 20 years.

“We started an appeal for donations, we held dances and managed to raise quite a lot of money. In fact, £300 came from the Cuban embassy and Tony Benn donated.

“In January 1984, we held a ceremony to install the stone. It was a cold day, but bright. The whole occasion was very moving.

“The Cuban and Chinese ambassadors attended. It was a triumph for each and every one of us. We planted two rose bushes; they’re still flourishing to this day and we take our grandchildren there, to pay their respects to Claudia.”

Part of Jones’s legacy lies in paving the way for the Notting Hill Carnival and Dr Claire Holder, a former director of the event, said some argued that she was not “mother of carnival,” since it began after she had died.

The vital beginnings, she said, came after the riots in the area in August 1958.

Claudia’s carnival parties were fundraisers so that young black men subsequently arrested could have legal representation.

The origins of what grew into the Notting Hill Carnival had come with Jones from Trinidad, said Holder, when people danced to mark the abolition of slavery, “Dancing had been prohibited. After the August 1838 emancipation, Africans resolved to celebrate a perpetual festival, to continue for three days.”

Holder joined her fellow speakers in welcoming the new book. “She has been all but ignored by the current generation, who do not realise that their rights have been fought for by the astuteness and doggedness of activists such as Claudia Jones.”

Delighted to differ with that view and amongst the 700 or so viewers of the online launch was 22-year-old YCL member Hannah Francis, who gave her own response:

“I’m mixed race (Jamaican and white British) and it’s impossible to sum up what Claudia Jones has done for Africans and the diaspora across the globe.

“Often labelled and appropriated as a stand-alone feminist icon, Jones was a vehement anti-imperialist, Marxist and proponent of intersectionality. Through different media — poetry, letters, speeches, organised action and more — she reached all corners of the globe, uplifting and unifying the working masses to organise against the Western capitalist and imperialist machine.

“Jones’s ability to create her own space in places she was not welcomed continues to inspire us. She must be recognised as a seismic contributor to the socialist cause, illuminating the presence of West Indians, as well as Africans and the rest of the diaspora, in organised socialist activity.

“After learning more about Jones over the summer and taking part in local Black Lives Matter protests, I decided to join the YCL. I decided with some other members to establish a YCL branch in Brighton and East Sussex which has been successfully recruiting new members since we set it up in July this year.”

Making a way for others to join in the struggle. It seems certain Claudia Jones would have been happy to hear that.