This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IN 2021 it is high time we spoke about Alan Winnington. People in South Korea certainly have been already.

His reports during the Korean war are currently being studied by activists and archaeologists alike, in order to find out exactly what happened at a place he visited just over 70 years ago.

I will write more about this shortly. But first I want to quickly introduce the man himself.

Born in 1910, Winnington was a man of his time — a Stalinist of the old school, working class, but with a scholarship to the prestigious Chigwell School in Essex.

His political opinions were informed by unemployment in the ’30s as well as the rise of fascism.

He carried a lump on his head from a police truncheon he encountered at Cable Street.

Moreover, he famously attracted the attentions of figures in the Communist Party when he unfurled an anti-Mosley banner from a Piccadilly hotel.

Largely because of this he was eventually made press secretary, which led to a stint at the Daily Worker, forerunner of today’s Morning Star, and then a role covering the revolution in China for it from 1948.

But his main reason for being sent to China was his passion, journalism.

The Xinhua News Agency needed training in good journalistic practice, and it was Winnington’s role to act as editor and adviser.

It was about “good propaganda,” but also the “effective communication” of ideas.

In China he delivered educational lectures called “What is News?” aimed at informing the burgeoning cadres.

It was these lectures that led to his undoing as the cultural revolution began to take hold in the ’60s.

Among other things this would see him having to escape to the German Democratic Republic with his wife and children.

There is much more to say about Winnington, but to truly understand his legacy you have to go back to the Korean war where he visited as the only English correspondent with the communist side from 1950 to ’54.

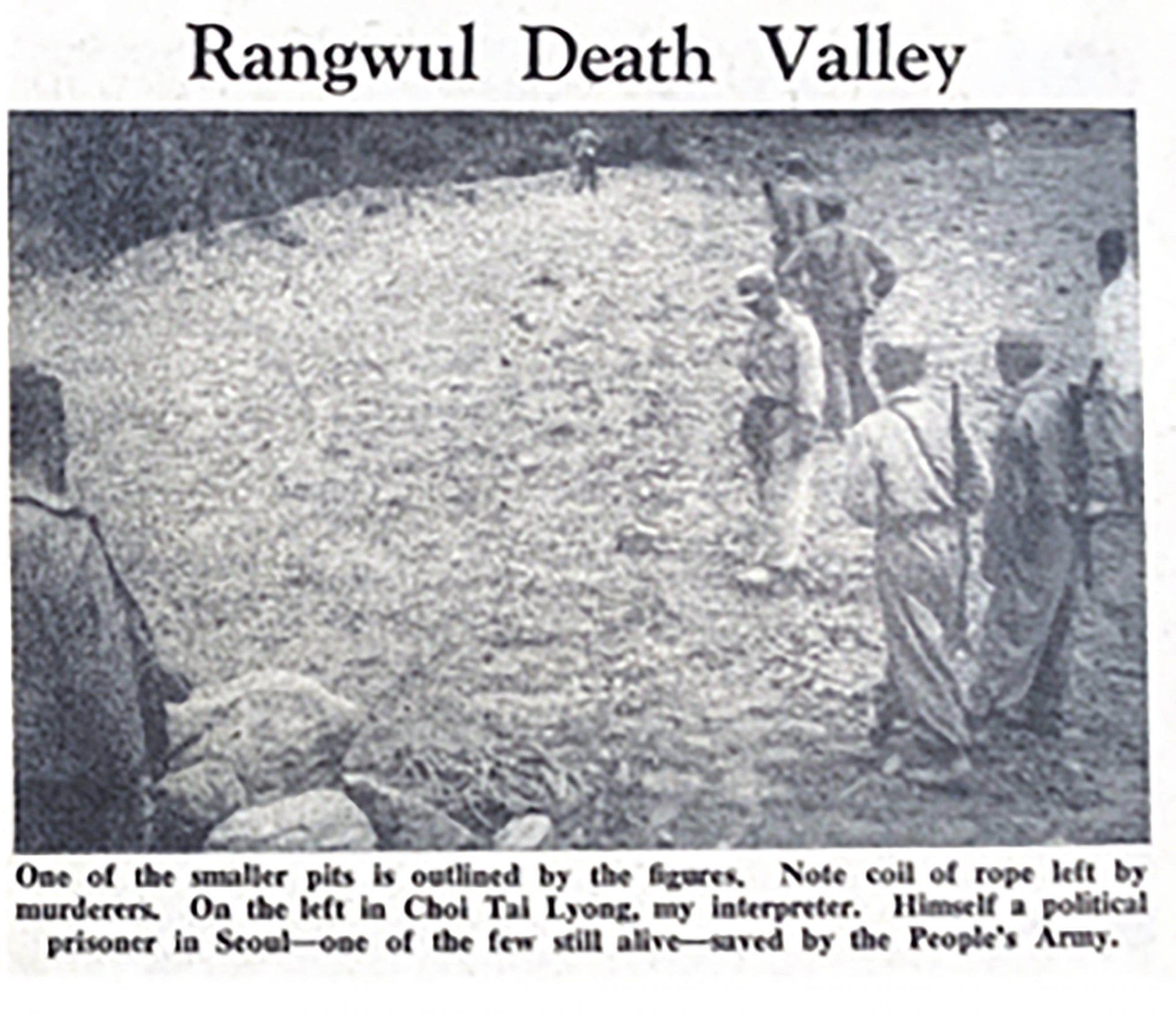

While there, Winnington took the following picture as part of his pamphlet I Saw the Truth in Korea.

Released in September of 1950 it showed what he had witnessed in a place called Rangwul (these days Nangwoldong in Daejeon).

The ramifications of his report all those years ago still provide evidence for a history that is only now beginning to be reckoned with.

The place he discovered was a valley called Gonrongol, but it has been changed by local people over the years to read Golonggol, incorporating the Chinese character for “bone”.

This subtle change gives the sense of a “valley of bones” where the terrain itself is indistinguishable from the reality of what Winnington discovered.

This valley is perceived by local people to be “the longest tomb” in the world.

Winnington’s pamphlet was bleakly aware of this. Under the picture was a graphic description of how up to 7,000 people had been murdered by the South Korean government under US “instruction.”

This was “politicide,” the murder of leftist opponents sanctioned by the unpopular South Korean leader at the time.

The details were startlingly well rendered.

“All six of the death pits are six feet deep, and from six to twelve feet wide,” claimed Winnington. “The biggest is 200 yards long, two are 100 yards long, and the smallest is thirty yards long.”

He took many more pictures, but had trouble developing them under wartime conditions.

Instead he cabled a report called “US Belsen in Korea” missing out the most important photographic evidence.

The pamphlet that came later was meant to set the record straight.

For Winnington’s trouble he was accused of “treason” and “supporting the King’s enemies” by Labour MP Hartley Shawcross in the House of Commons.

For his contact with prisoners of war in North Korea, and his reports in general, he was eventually deprived of his passport entirely.

“Perhaps his Chinese friends can help with out with documents,” sardonically uttered a spokesperson for the British consul in 1954.

It was only thanks to pressure on the government that he eventually had his passport reissued.

This peaked when the journalist Neal Ascherson wrote an article in 1968 comparing Winnington’s plight to that of Paul Robeson who had suffered similar travel restrictions in the US.

Since that time his reports have slipped through the cracks of history, only to resurface now that evidence is desperately needed for a Peace Park that will be built here in 2024.

The story doesn’t end there either. In 1999 (16 years after Winnington’s death), images were released by the National Archives in America of pictures by a Major Abbot that showed the Daejeon massacre in process.

These confirmed his original report and provided gruesome new evidence of what went on.

The picture below has become representative (the person staring helplessly into the lens has since been identified by his family members).

It is impossible to imagine the callousness it takes to click the shutter of a Leica camera in the last moments of someone’s life.

Winnington’s claims of “American instruction” are impossible to corroborate, but they were certainly present in an observational role.

A note by Lt Col Bob E Edwards among the 18 pictures noted that 1,800 people had been killed at this time.

What the photos actually showed was the first of many such massacres in this valley from June 28 to July 17.

There were at least eight in total. In the plans for the Peace Park the main burial sites Winnington discovered, including a 200-yard “pit,” will form the basis of an architectural plan whereby a variety of buildings intersect in “metonymic juxtaposition” with the excavations themselves.

It will be a place for reflecting on, and remembering, a complex tragedy about which people still know very little.

The excavations are increasingly helped by Winnington’s photos such as in the “before and after” comparison with Abbot below.

These are very rare images and testament to the meticulous way in which Winnington approached the scene.

It seems strange that something of such historical importance is only coming to prominence now.

This was clearly not the case in 1984, where at Winnington’s wake at the Marx Memorial Library his family and friends remembered everything.

After the ceremony his two sons vaulted the gate of Highgate Cemetery to sprinkle his ashes on Marx’s grave.

Perhaps this was the ultimate symbolic act of remembrance for someone who spent his whole life in thrall to his ideas.

The main issue, as the historian Tom Buchanan has explained well in his text East Wind (OUP, 2012), has not been Winnington’s journalism as much as the intense battle over ideology that defined the Korean war in the first place.

It is possible to rely on Winnington’s account in this climate only because of the incontrovertible evidence it still provides.

It is this data that makes Winnington’s contributions of increasing importance.

His journalism will certainly be represented in the Peace Park when it is built.

Whereas an archive at Sheffield University will provide material that will be increasingly useful in later years.

During January in South Korea an exhibition including Winnington’s photos will take place in Daejeon for the first time.

This is only the beginning of a series of engagements. For a man once accused of “treason,” and exiled from his own country, it is incredibly good news.