This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

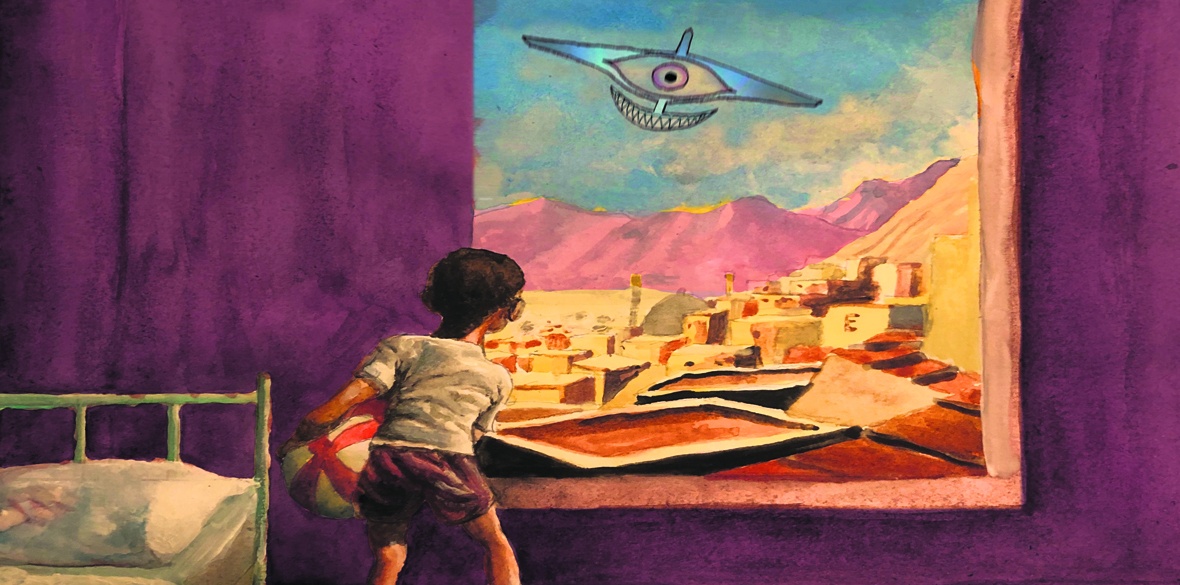

IN 2013, a 13-year-old Pakistani boy named Zubair told the US Congress, “I no longer love blue skies. In fact, I now prefer grey skies. The drones do not fly when the skies are grey.” Though the spectacle of Donald Trump’s presidency has obscured the discussion of drone attacks, which had begun in Barack Obama’s trigger-happy tenure, remote strikes by the US military have increased since 2016. And they have gone under the radar. In 2019, the Trump administration revoked a policy requiring intelligence officials to publish the number of civilians killed in drone strikes outside war zones.

So, with Pakistani boys afraid of clear, blue skies and the civilian death toll from remote warfare now obscured from view, it’s necessary to ask — how did we get here?

The ascendance of remote warfare, and the ubiquity with which it is utilised today, have been a long time coming. Though the modern, weaponised drone may seem a recent invention, its conceptualisation goes back more than a century.

It’s a strange story which involves a man falling from a cathedral, Marilyn Monroe, the Israelis — and ends with a group of pilots sitting in a room just outside Las Vegas.

The story begins in September 1858 with a young building surveyor named Albrecht Meaydenbauer attempting to measure, by hand, the facade of Wetzlar cathedral. When Albrecht fell from a ladder, the accident almost killed him and, as he lay in hospital recovering, he decided that measurement by hand — the long-established method — was too dangerous.

As fortune would have it, his accident coincided with the infancy of photography, and Albrecht realised that direct measurements could be replaced by indirect measurements in photographic images — a process that became known as photogrammetry, the progenitor of the verticle image, utilised by remote warfare today. Back then, the verticle view, often surveyed via hot-air balloon, was a revelutionary way of looking at the world — now it is the shorthand for all navigational and surveillance modes.

The idea of a drone, or telechiric machine, was initially floated as a way of exploring inhospitable zones, and it wasn’t until the second world war that a militarised drone was considered, with the aim of minimising human involvement in warfare.

First came “target drones,” small remote-controlled planes for US artillery target practice. But it wasn’t long before the military-industrial complex thought to weaponise the concept and set thousands of factory workers to construct them. One of these workers was a girl by the name of Norma Jeane Dougherty, who had her first break in a photo for the Radioplane Company, launching an acting career as Marilyn Monroe.

The drones of the second world war were not particularly successful. However, during the Vietnam war, the US army developed “lightning bugs” to disrupt Soviet surface-to-air defences. This project was subsequently dropped and the lightning bugs destroyed — but for a few which found their way into the hands of the Israeli Defence Force, which developed a new programme.

The Israelis made startling use of their drones to gain mastery of the skies during both the Yom Kippur war against Egypt and the 1982 conflict with the Syrians over the Beqaa Valley. The drones would flood in, distracting the enemy air defences, allowing manned aircraft to take them out in a follow-up wave.

With strong ties between the Reagan administration and the Israeli Defence Forces, the United States began to take heed of the drone’s potential. However, at this point, despite their effectiveness, drones were used only for intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance — they were just eyes. The mutation to an offensive weapon came later.

What is the function of a drone? It is to create a reality in which death is impossible for its controllers.

And ironically, it was after the advent of the suicide bomb — a reality in which death is certain — used by the Japanese kamikaze pilots of World War II, then by Shi’ite militants in the Lebanese civil war and the Tamil Tigers of Sri Lanka, that the drone strike emerged.

It came about at the turn of the millennium, between the wars in Kosovo and Afghanistan, when General Atomics invented a prototype, unmanned spy-plane that it called the Predator.

Around the time of the September 11 attacks — the most infamous utilisation of the suicide bomb — the US military thought to equip the Predator with an anti-tank missile. The first successful test came on February 16 2001 and live targets followed later that year.

George W Bush’s “war on terror” turned the notion of military conflict on its head. The proposed enemy was a clandestine, nebulously defined one and an “international manhunt” was initiated in search of Osama Bin Laden.

Historically, the US government had never been particularly successful when it came to international manhunts. An expensive early failure came in 1916, when General John J Pershing launched a supranational military offensive to hunt down Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa.

Now, however, with eyes and claws in the sky, the US government was altogether more confident and then-defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld sent countless Predator drones into the Middle East.

By 2009 and the onset of the Obama administration, drones were a ubiquitous tool of the US military — from Somalia to Syria, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Obama authorised a known total of 542 drone strikes during his eight years in office, killing a total of 3,797 people, among them 324 known civilians.

By his second term, drone attacks had become so normalised that the president felt comfortable making this joke in one of his gala speeches: ‘“The Jonas Brothers [a US pop-rock band] are here … Sasha and Malia are huge fans. But boys don’t get any ideas; I have two words for you — predator drone.”

Just beyond the bright lights of Las Vegas lies a compound. On its gates, emblazoned on steel, are the words Creech Air Force Base — but soldiers know this place as “The Home of the Hunters” — and it’s from here that many of the drones, currently stationed in the Middle East, are controlled.

The pilots sit in front of vast control panels, fingers poised, deliberating whether or not a gathering of people in Pakistan constitutes a wedding or a terrorist conclave.

Drone pilots are said to suffer from extremely high levels of mental illness, so are subject to constant psychiatric scrutiny. With such a dislocation between the initialisation of violence and its consequence, wired-up to a faraway weapon, the mind can easily break.

Walter Benjamin wrote that the action of future wars will lose their “military character” presenting a new face “which will permanently replace soldierly qualities with those of sports.” This is indeed happening.

On a conceptual level, we here in the West have entirely become divorced from the consequence of warfare — just as the religious fundamentalist, rigged to explode, has become divorced from the idea of himself. How bad will this become? How far must we drift, as a society, from the accountability of our violence? The vertical image, once used to measure cathedrals, is a transmutation of the living into the virtual, a conversion of the human into the dot.

Here is the transcript of a recorded conversation between a pilot, mission intelligence and safety observers from the Nevada Base in 2010, just after a strike was initiated:

Intelligence co-ordinator: Is that two? One guy’s tending to the other guy?

Safety observer: Looks like it.

Sensor operator: Looks like it, yeah.

Intelligence co-ordinator: Self-aid buddy care to the rescue.

Safety observer: I forgot, how do you treat a sucking gut wound?

Sensor operator: Don’t push it back in. Wrap it in a towel. That’ll work.

Pilot: They’re trying to [expletive] surrender, right? I think.

Sensor operator: That’s what it looks like to me.

Intelligence co-ordinator: Yeah, I think that’s what they’re doing.

Sensor operator: What are those? They were in the middle vehicle.

Intelligence co-ordinator: Women and children.

Sensor operator: Looks like a kid.

Safety observer: Yeah. The one waving the flag.

Sensor operator: I’d tell him they’re waving their…

Safety observer: Yeah, at this point I wouldn’t … I personally wouldn’t be comfortable shooting at these people.

Intelligence co-ordinator: No.

The drone does not simply beset us with a political question but a metaphysical one: how we see dictates who we are.

Miles Ellingham is based in London and works as a writer and poet.