This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

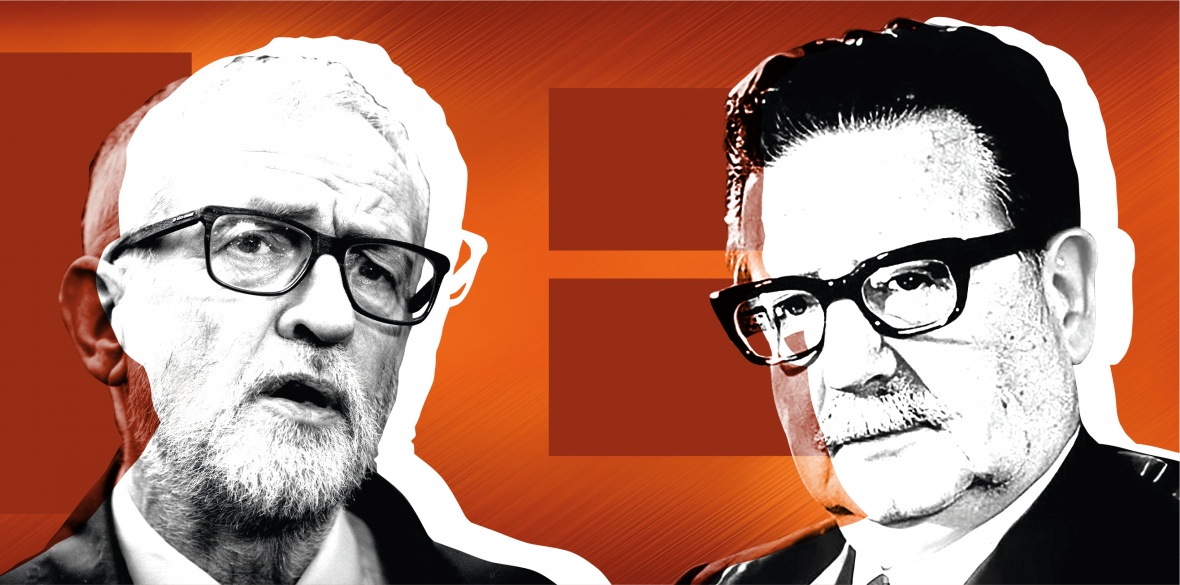

THIS week marked the 50th anniversary of the historic election of Salvador Allende to the presidency of Chile, as well as the 47th of the bloody coup that overthrew and killed him.

I was delighted to be joined by Jeremy Corbyn, friend to the Latin American left — in particular in Chile — in Finsbury Park.

In this interview, we discuss his time spent in Chile in the build-up to the 1970 presidential election, asking him what Allende’s victory meant for the left across Latin America and the world at the time.

Can you tell me about the beginning of your time in Chile, what made you aware of popular unity?

Jeremy: I was in Chile in 1969 when Popular Unity was formed — I was on the May Day march there and it was all very tense because people weren’t sure if the left alliance was going to work.

Allende had been a long-term senator, had run for president before and he was the choice to be the presidential candidate.

What was nice about it and different was the music and diversity of the march.

Later during that period, I went to a folk concert in Vina del Mar, which was an assertion of the urban left, but also of the involvement of the indigenous people. Then the fault line of most Latin American politics was that the left had been dominated by European Marxist and socialist ideals and it hadn’t encompassed the traditions of indigenous communities.

Most of the left parties were led by people of European descent.

Then the elections took place and we kept getting reports in various papers, the best reporter in all of this was Hugh O'Shaughnessy of the Observer and the FT at that time. He had the best analysis of it.

We were sort of thinking they can’t do it … I remember staying in a flat in Santiago.

There were a lot of young British and French people in this flat, most of whom were associated to the Socialist Workers Party here or International Socialists as it then was, who were unenthusiastic about most of it really.

Enthusiastic for social change but [they] wouldn’t believe that the Popular Unity and from their point of view, the Communist Party was a good thing.

It was impossible to do it without the Communist Party in Chile at that point, so the Communist Party and Socialist Party coming together was absolutely crucial — there was no way they were going to win without each other.

Allende got the largest vote but in fact it wasn’t a direct vote, it was an indication to the congress to elect the president on the basis of the popular vote — but they didn’t have to follow it.

There was a suspicion that the congress, which did not at that time have a left majority, would not have voted for Allende, that they would not confirm the election result.

They did, but I was never sure how much of this was paranoia amongst Allende supporters or whether it was real.

Many closer to the scene would know better than me on that one.

He was confirmed as president, and his achievements were amazing in a sense of giving hope and enthusiasm to people to really change their lives.

That’s the exciting thing about it — if you talk to any older Chilean person who was around at that time, they don’t remember it as a time of particularly easy living, it wasn’t. There were shortages — all inspired by the blockade.

There were problems because of the pressure of the far right — but it was a time of hope.

A time of inclusion of people in a way that had never happened before.

Some of the poorest got housing, the children got milk in school, schools were better resourced and there was an attempt to start to at least treat the indigenous people decently — that hadn’t happened before as Chile was seen as the “Europe at the end of Latin America.”

Chilean film-maker Patricio Guzman calls the conflict in Chile in the build-up to the 1973 coup, “the insurrection of the bourgeoisie vs the power of the people.”

When did you become aware of the changing situation in Chile? What were the repercussions of those events for Latin America and the democratic socialist left across the world?

Jeremy: I followed everything very closely that was happening in Chile from 1970 onwards.

From 1971 where I worked for the Union of Taylors and Garment workers, we had all of the newspapers — I was in the research department.

I kept cuttings of the articles Hugh O’Shaughnessy wrote about Chile.

There were discussions on the left in London in support of Chile — there were some who said the project was unsustainable, and that the only way forward was outside parliament, while others disagreed, and it was that sort of debate.

Then things were obviously getting worse in Chile.

On the night of the coup I stayed up all night as I had a friend who worked as a copy clerk in Reuters and he was getting the cable in every two minutes from Chile and he was then phoning me up and reading them to me.

It was horrible, absolutely horrific. We felt this sense of anger and powerlessness at what was going on.

That afternoon word went around on what was happening, so we decided to have a demonstration outside the Chilean embassy.

So we went to the Chilean embassy on Devonshire Street and a whole lot of us turned up and stood there, made slogans and all of that sort of stuff.

But then somebody appeared on the roof of the embassy and we thought what is going on?

Then this person on the roof of the embassy looked at us all and raised his fist in solidarity.

It was Alvaro Bunster, who was the ambassador. He had come to express his solidarity with us.

I met Alvaro years later in Mexico, he went to live in Mexico. I just said what a moving occasion that was for all of us. He said he was overwhelmed, that people had come in support.

When the Chile Solidarity Campaign was founded, and a lot of Chilean exiles came here, one of their heroes was Judith Hart, who was a minister in the Labour government.

She helped to ensure settlement of quite a lot of Chilean refugees. There were a lot. I was a councillor in Haringey at the time. We got some Chilean refugees housed — the GLC housed some in Thamesmead and other places — so there was a growth of a Chilean community.

The ones who got to Britain tended to be the most articulate left activists who managed to get out, either by the Mexican embassy or the Cuban embassy, some staying for months and months.

Some went to Mexico and from Mexico some went to Cuba — others went to Sweden.

After the Cambio de Mano (“Change of Hand”) back to a form of democracy in 1990, the new ambassador from Chile invited me to come to the embassy to see him.

I was walking down Devonshire Street and I suddenly found myself standing in the exact same spot I stood at in 1973 — the same drain cover was still there.

I was looking at the embassy and thought actually I’m supposed to go in this time. I had never been in the embassy before.

What are the lessons we can take now from the struggle in Chile, 50 years on from the election of Salvador Allende?

Jeremy: Understand that the power of international capital and global corporations is enormous and huge.

It will be used against any progressive government and the only way forward is to have strong labour movements and a strong cultural movement goes with it — that unites people in the understanding of hope and expectation that we don’t have to live in a world of global inequality.

Tom Raeside is a Young Labour activist from north-east England, member of the People’s Bookshop Collective in Durham and is studying history at Goldsmiths.