This is the last article you can read this month

You can read 4 more article this month

You can read 4 more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

SOMETIMES it is worth stress-testing received wisdom and long-held political assumptions.

One such is the argument that Labour is a trade union party. There is little dispute that it was founded as such. But today?

Stating that Labour remains the political expression of organised labour underlines the importance of independent working-class politics, and draws attention to the continuing fact of trade union affiliation.

It is also a formulation that can choke off fresh thinking, a sort of “top trump” card which asserts Labour’s political value irrespective of any other strategic development.

It has always been a complicated story. Labour was certainly created as a trade union party, but not as a socialist one — socialist groups were very junior partners — so on its own that is not a compelling model for socialists.

Socialism, of a Fabian flavour, officially came in with individual membership after WWI, which opened Labour’s doors to liberals and other non-trade unionists.

The Establishment never liked Labour’s trade union foundation, so it set out to vitiate it from the outset. One measure adopted in the 1920s was a prohibition on unions sending communists as delegates to Labour Party conferences and organisations, a violation of unions’ own democratic sovereignty.

Just as significant was the entrenchment of parliamentary supremacy within the party’s structures. Unions retained a key organisational and financial role, but policy was the preserve of parliamentarians, who determined the party’s conduct in government.

The party leader was, until the 1980s, merely the leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party, and elected by MPs alone. Trade unions for the most part went along with this, bowing to the logic of bourgeois constitutionalism.

Nevertheless, unions themselves remained democratic and therefore somewhat unpredictable class organisations. When I first started attending Labour Party conferences for this newspaper — in the 1970s, if you’re wondering — the unions together had about 90 per cent of the vote there.

Trade union delegation meetings were where a big part of the action was, and they were fiercely contested by different trends.

Labour’s official policies were therefore what trade unions said they were. The issue became what, if anything, Labour’s parliamentary supremos were going to do to implement them.

A lot of passion was expended on that question, but by the time the question of Labour in office became real again, much had changed. The Economist newspaper editorialised in the early 1980s that no party constitutionally dependent on organised labour must ever be allowed to rule Britain again.

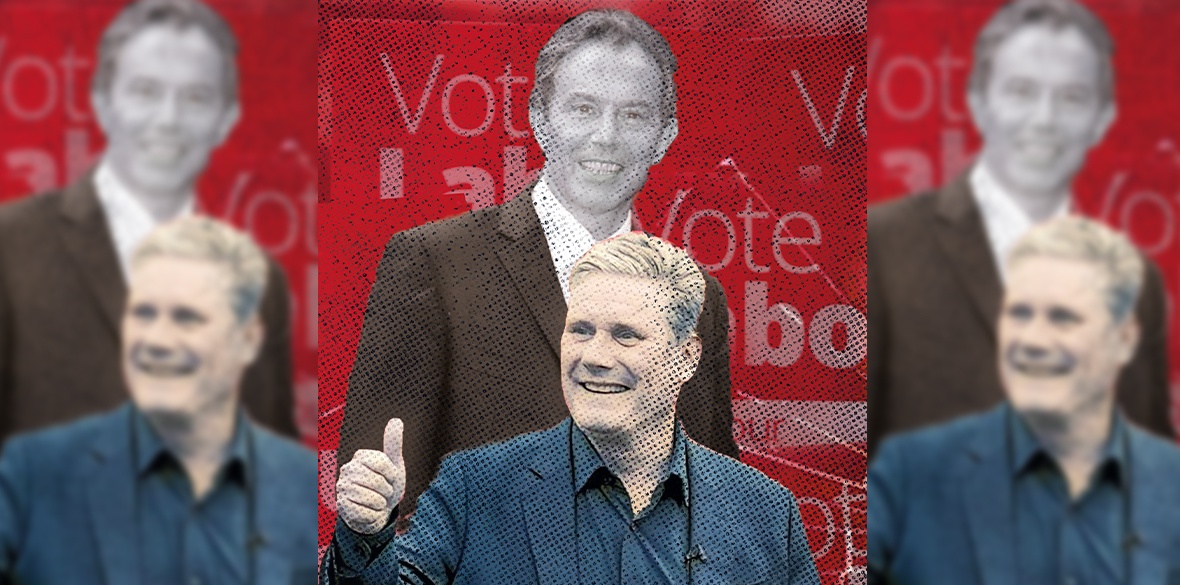

Labour’s right-wing, now morphed into the New Labour project of Blair and Brown, acted on that class war injunction. They determined that trade unions were bad at the box office and had to be visibly kept at arms’ length.

Again, unions largely acquiesced in both constitutional changes diluting their influence and in patronising disparagement from New Labour’s head honchos.

They wanted the Tories out. Moreover, back in society at large, trade unionism had a lot of its stuffing knocked out of it in the 1980s in a story too well-known to need retelling here.

It is easier for a party to challenge for power as a union party when the unions speak for half the workforce and are deeply entrenched in a range of industrial communities than when their membership is crumbling and their influence diminishing.

Trade unions increasingly settled for being just another pressure group within their own party. Their financial contribution was itself matched by donations from wealthy individuals.

The latter gave the Blair machine cash in the hope of passage to the House of Lords — or at least quite a striking correlation eventually emerged. To be fair, those donors would meet a lot of retired trade union leaders on the red benches when they arrived.

But it was not all passivity. From around 2003 onwards the larger trade union affiliates started to get their act together. With still half the conference vote at their command a united trade union position, given even minimal constituency support, could find a way through the labyrinthine policy-making maze.

Thus, votes were won at Labour conferences against the government on a range of questions — public service privatisation, railway nationalisation, the right of unions to take solidarity action, council housebuilding etc.

Here the significance lay in what, in the manner of Sherlock Holmes’s non-barking dog, did not happen. In fact, nothing happened at all. Blair and then Brown felt under no obligation to act on the conference decisions, and thus entirely ignored them.

The unions themselves were then powerless. What further could they do to impose their democratically sanctioned will? Reducing election funding was a feasible option, but one very much in cut-nose-spite-face territory.

So the parliamentarians continued calling the shots, and the argument that they only got away with their sundry betrayals because the unions tolerated it was shown as false. Whatever unions thought or did was all but immaterial.

Today, matters are worse. Firstly, Keir Starmer has run away from progressive positions on almost every issue, including most recently workers’ rights, and only Unite, among the larger union affiliates, has raised a public peep.

Secondly, candidates supported by virtually every affiliated union have been blocked by the Starmer apparatus from even being considered by constituency parties. That is a historic negation of union influence.

Thirdly, the Labour Party hierarchy has turned its back on the upsurge in union industrial action over the last year, supporting neither workers’ demands nor the struggle to secure them.

There are further complications. Unions never affiliated to Labour have grown in relative weight within the TUC, making a common electoral expression of trade unionism formally challenging.

And the constituency left is sometimes at resentful odds with the unions. This happened on several occasions in the Corbyn years — some leading leftwingers even spoke of “breaking the link.”

What could be concluded from this summary sketch? The basic question — is Labour still a trade union party — can only be answered either with a “yes, but” or a “no, but.”

For the great majority of voters, including working-class voters, however, it is no longer a very interesting question — more labour theology than an issue with practical consequences.

There is no reason to believe that a union attempt to use the party’s procedures to impose a more progressive agenda on the Starmer gang would be any more successful than it was under Blair and Brown.

Working-class pressure, including by trade unions, can certainly affect the course of a putative Starmer regime, but such action could under any circumstances, not as a result of affiliation. Protest, not process, will be key.

If the end — socialism — is everything, the left should probably not accord overweening significance to the residual evidence of Labour being meaningfully a “union party.”

The 20th century is over, although Lenin’s description of Labour as a “bourgeois workers’ party” may still be helpful. Right now, the adjective is ascendant.

The problem is less that unions don’t run Labour as much as that the movement as a whole remains self-shackled by constitutionalism and pragmatism. There is the struggle.

Whether Labour remains a site of that struggle will only become clear when a real movement starts to press against the prevailing bureaucratic authoritarianism. Today, the question seems more slightly ajar than fully open.