This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

I WANT to dedicate these words to a friend of mine, Blair Peach, who was murdered by the police 40 years ago.

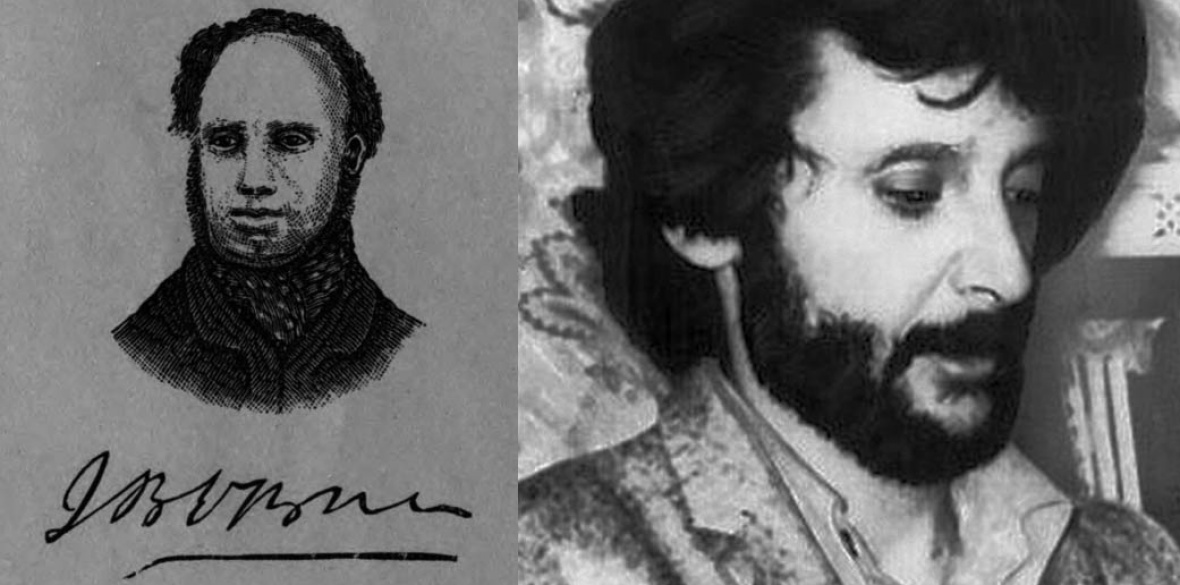

Blair lived in Hackney — he too, like Bronterre O’Brien, came to this country from abroad — from New Zealand — and became politically active here.

He was an educationalist dedicated to the education of working-class children in Tower Hamlets where we worked together and he was a passionate campaigner against racism and social injustice — a revolutionary.

We were neighbours, colleagues, friends and comrades in the National Union of Teachers. The truth about what happened and how he was murdered was known — indeed the names of the culprits were known 40 years ago — yet the truth about what happened is still being suppressed by the state 40 years later.

In this respect there are similarities between the way the state reacted to the events in Southall in 1979 and the manner in which they acted during the period of James Bronterre O’Brien.

The name James Bronterre O’Brien captures the imagination. It is one of those names that resonates with me like the names of numerous other Irish revolutionaries and radicals — Theobald Wolfe Tone, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde, Constance Markievicz and James Connolly and, of course, further afield in Latin America Bernardo O’Higgins and Ernesto “Che” Guevara Lynch.

But in each case naturally there is much more to these names than their sounds and romantic associations.

We know what often happens to individuals whose names cannot be fully eradicated from history or ignored — especially those of the more radical and revolutionary characters. The Establishment, if they can’t erase the name from history, will try to strip them of their full history or context and then try and appropriate it.

We only have to think of Nelson Mandela, now deified by the very people who once vilified him — Mandela the man, the “terrorist,” who went to jail for refusing to renounce the right to armed struggle being turned into a pacifist.

I don’t think we should let this happen to O’Brien, nor to any of the countless men and women who have fought to bring about change over the years.

The more I read about O’Brien the more interesting he became on a variety of levels, including at a personal level. On several occasions he visited my home town of Stockport. From there he was elected as a delegate to the Chartist movement National Convention.

O’Brien, born in 1805, left Ireland in 1829 — a decade later on January 7 1837 he wrote of his experience, saying: “My friends sent me to London to study law; I took to radical reform on my own account … While I have made no progress at all in law, I have made immense progress in radical reform. So much so, that were a professorship of radical reform to be instituted tomorrow in King’s College (no very probable event by the way), I think I would stand candidate … I feel that every drop of blood in my veins was radical blood.”

What is interesting is the role that Irish radicals played in the development of politics in England, as in literature. Wilde, Shaw, Yeats, Joyce, Beckett, O’Casey — the outsiders unconstrained by the conventions of the society of the day. They were all both familiar with and yet distant from what they met.

The times that O’Brien found himself in England were revolutionary. They were shaped by many factors — both international and national factors were influential. The American war of independence ended in 1783 and the French Revolution began in 1789.

The “special relationship” which many radical reformers had with America in the early 19th century was a consequence of revolutionary aspirations, not the conservative deference of the 20th and 21st centuries.

The Red Bonnet of the French Revolution was frequently hoisted at their demonstrations, as in Stockport in February 1819, and also ceremoniously burnt by the forces of reaction. In the background was also the uprising of the United Irishmen.

In October 1818 in Stockport the wonderfully named Union for the Promotion of Human Happiness was established — no doubt many of them veterans of the cotton workers’ strike of 1817-18 against cuts to their wages.

In 1803 weavers had been earning 15 shillings for a six-day week — by 1818 this had been cut to around five shillings.

More than once their strike actions were broken up by special constables and yeomanry, on one occasion resulting in the killing of one of the demonstrators — who the magistrates determined had “died by the visitation of God” — a 19th-century version of the coroner’s verdict on Blair Peach: “death by misadventure.”

On February 11 1838 O’Brien attended a dinner in Stockport at the Stanley Arms where he was elected to replace Joseph Rayner Stephens as a delegate to the Chartist National Convention. Money was collected for the “national rent,” the Chartists’ central fund, and a petition was collected with 13,000 names.

What is impressive reading about this history is the scale of mobilisation and the level of organisation involved.

But school students are seldom, if ever, taught this as part of their history — the history curriculum in schools is all about kings and queens and their bastard offspring.

O’Brien of course hardly appears in the formal “official” version of English history — like countless other figures of radical or revolutionary backgrounds, who only appear in passing or as victims: the defeated, footnotes to be quarried by aspiring PhD candidates. As the historian Avi Shlaim and others have said, history is written by the victors — and that is still happening today.

There are numerous examples of the rewriting of history in which the full story is suppressed beneath an authorised version — one of the most stark and gross examples of this remains the myth-making around events associated with the British empire like the so-called Indian mutiny of 1857.

In truth this was a major Indian anti-imperialist struggle against the British — of course made more palatable by being described as a struggle against the British East India Company, which might be described as the very apotheosis of the close relationship between the state and capitalism.

At yet another level of distortion is the way in which the accounts of what is called the second world war are presented. This was of course several wars — inter-imperialist, national liberation, anti-imperialist, wars of resistance.

According to popular Hollywood history, German and Italian fascism were defeated on the western front solely by US and British troops. The truth of course is much more complex — almost three-quarters of the fighting in the European theatre took place on the eastern front and it was the forces of the then Soviet Union which defeated the nazi armies.

This rewriting of history takes place especially at the domestic level. In recent years we have only to think of Southall and Orgreave — there is a long list — more often than not rewritten as part of an attempt to promote a version of history that portrays all change in society as the product of gradual peaceful transitions.

The real struggle, imagination and courage of those who fought for change is buried beneath a sanitised narrative in order to appropriate it and incorporate into a version of British history as a seamless peaceful linear progression, only occasionally besmirched by the actions of thoughtless and cruel individual members of the ruling class untypical of the class they belonged to or the age in which they lived.

Paying tribute to the memory of the men and women of his era, acknowledging the role of the organisations they built like the Union for the Promotion of Human Happiness and, of course, the Chartists and the actions they took is a small way of preserving and reaffirming the role of the real history-makers who, alongside James Bronterre O’Brien, thought that the promotion of human happiness was something worth fighting for.

Dr Bernard Regan gave this year’s Abney Park Trust Bronterre O’Brien Commemorative Address. He is a former member of the NUT (now NEU) Executive body; he is a leading activist in Cuban and Palestinian solidarity work and is the author of The Balfour Declaration: Empire, the Mandate and Resistance in Palestine (Verso).