This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IN 2021 the Daily Worker (predecessor of today’s Morning Star) correspondent Alan Winnington’s photographs returned to Korea. They were part of an exhibition detailing a massacre in July 1950.

These mass killings were of around 1,800 to 7,000 “leftists” in the early stages of the Korean war. They had taken place at the outskirts of a city called Daejeon.

Winnington wrote about this incident in his pamphlet I Saw the Truth in Korea (1950). The journalist only took photographs at this one place, but he heard stories of similar massacres in every town and city he visited.

In Daejeon the pictures he took contributed greatly to the excavation of remains from 2020 onwards. It was to highlight this aspect of his journalism, and the Peace Park to be built on site in 2024, that the exhibition took place.

Today the 1.5 million people in Daejeon know little of these massacres. There is good reason for this. When discussing the controversy of the Picture Post’s reporting during the Korean war in 2019 Winnington’s first wife Esther objected to the word “censored.” Esther, who saw events unfold at the time, prefers the more unequivocal “suppressed.”

The curious patina, and damage, afflicting some of Winnington’s photographs today highlights this. Instead of being examined by the relevant authorities, they were filed away with personal effects, not surfacing properly until 2020.

It is almost as if the apathy and disdain with which they were originally greeted in Britain is marked on their surface. Willed out of existence, they have become visual metaphors for their reception.

The title of the exhibition — At This Place We Saw the Truth — originated in its attempt to publicly display Winnington’s images for the first time.

This was an exclusive opportunity, thanks to the co-operation of Sheffield University. The exhibition was a deliberate attempt to replicate the tone and urgency of Winnington’s dispatches. I Saw the Truth in Korea provided the theme.

This was the idea of local activists Shim Gyusang and Im Jaegeun. The goal was therefore an updating, and re-evaluation, of the journalist’s aborted attempt at truth-telling in the light of the present-day excavations.

It aimed to put the struggle of the families and activists on site in the context of the Peace Park itself. The journalist’s photographs were central to this.

The images were chosen based on their importance to the excavations, but also in terms of biography. It must be recalled that in 1950 Winnington’s reports were labelled a “fabrication.” Seeing them in this context was very encouraging, even if it came 70 years too late.

In many ways the exhibition was premature. The process of recovering the remains is not over. It is an extremely difficult and laborious task.

For the families of those killed everything else is a distraction. Until there is some sort of closure, and access to the truth of what happened, this will be the case.

The valley in which the photographs were originally taken by Winnington has seen much attention this year. As well as primetime KBS and MBC documentaries, there have been many other attempts to explain the reality of what happened.

What is always missing is a sense in which this tragedy can be communicated to the world. This was, after all, Winnington’s original intention. It was a humanitarian intervention muted by what Esther called the “warmongers” during her speech at the memorial in 2019.

The suppression of information during the Korean war has left lingering and unsuspected traces. Winnington’s photos are only the best known example.

Often this important data is not in university libraries, but private collections instead. At the end of this year I was fortunate enough to visit Ursula Winnington and her daughter Maraike in Berlin.

My goal was to get a sense of the toll the Korean war had taken on Winnington, but also fill in any gaps and misunderstandings in terms of my own research.

Ursula is Winnington’s second wife. They were married in the German Democratic Republic, and lived together from 1968 onwards.

The journalist had moved to Berlin after leaving China in 1960. This was just before the Berlin Wall was erected.

Now that it no longer exists, it is getting increasingly hard to imagine the city Winnington lived in at all. Such tensions were most visible at the site of the old Palast Der Republik.

Called “Erich’s lamp shop” by locals, the old lamps that had given it this moniker were being sold to Berliners for €4,000 each at the newly opened Berliner Schloss.

The statue of Marx and Engels is close by. It is hard not to imagine each of them grimacing at the resuscitation of this old centre of imperial power.

Winnington must be grimacing too. But he would also have seen such changes as inevitable. In an educational textbook for Chinese cadres — called What is News (1949) — he writes about the importance of “existing in the fight of words.”

Unless communist reporting was so arranged, Winnington claimed at the time, it would become subsumed into the dominant history surrounding it.

It is clear that his pamphlet, and the many other attempts to communicate what happened in Daejeon in August 1950, were part of this “fight.”

The journalist was very aware that “bourgeois editors” would sooner deny his reports than engage with them. His was a political writing permanently under erasure.

The reception of Winnington’s reports on the Daejeon massacre confirms this. The only time they were mentioned in the mainstream press directly was in reviews of his memoirs — Breakfast With Mao — in 1986.

These memoirs were written very deliberately at Winnington’s summer house from 1980 onwards. The journalist, having reached his seventies, was clearly in a reflective mood.

“It seemed,” Ursula has told me in interviews, “he wanted to get something off his chest.” The journalist had attempted to publish a book on the Korean war in the ’60s to no avail.

At the time he was writing detective fiction. This was the only time he returned to the topic of Daejeon or the Korean war. The passage on the massacre in Winnington’s memoirs includes information his family tell me he rarely talked about in person. It is clear Winnington had lived with these memories for nearly 30 years.

Reports from South Korea, suffering terribly in a dictatorship at that time, must have been in the news as he completed it.

Focusing on the Daejeon massacre again came out of duty, but also the sense he was having the “last word.” The “British or US governments confirmed my reports by failing to disprove them,” wrote Winnington, “when it would obviously have been possible if they had been untrue.”

It is this historical injustice, combined with the building of the Peace Park, which led the mayor of the East District of Daejeon to contact Ursula in 2020.

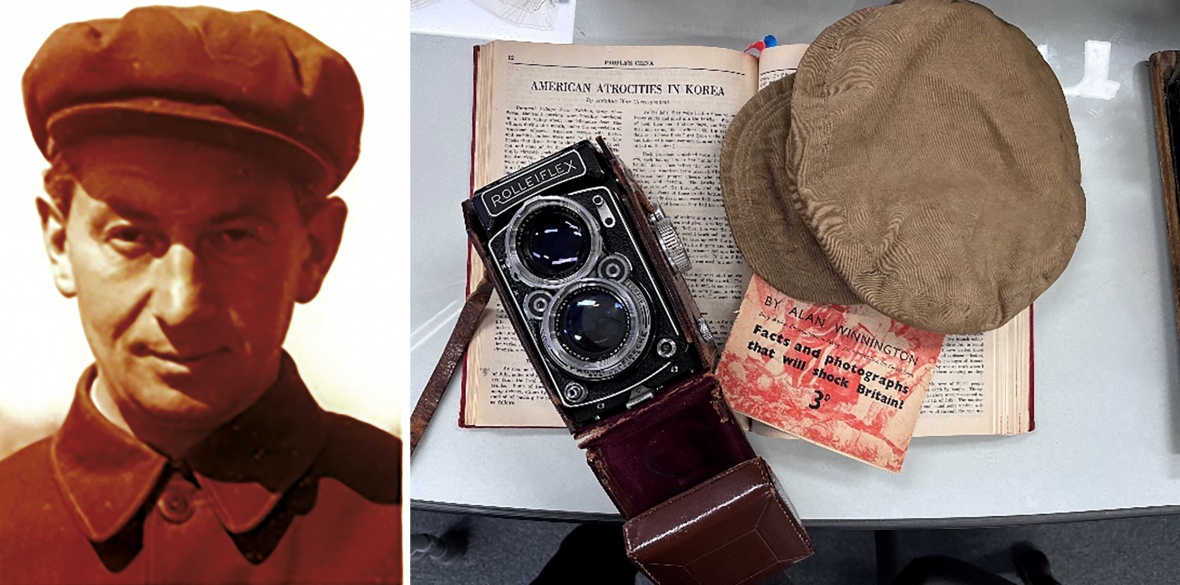

Alan’s typewriter, camera and other items were donated as a result. Ursula generously handed them over on my visit. It is a cliche to wish historical objects could speak.

But if they could Winnington’s battered mementos from the Korean war would speak a reality like no other. If it is too late for them to bring comfort to the bereaved families, let’s hope they will be displayed in Daejeon as a testament to Winnington’s journalism. Not only as an acknowledgement of the difficulties in truth telling, but as a message of solidarity and peace.