This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IN THE same week that the defence committee blasted “failed” mental health provision for veterans, a new report entitled Selling the Military has criticised military recruitment advertising for targeting groups, particularly disadvantaged children, who are likeliest to suffer adverse outcomes.

Written by military watchdog ForcesWatch, health charity Medact and with contributions from academics and veterans, the report calls for greater scrutiny and regulation of military recruitment marketing on health and ethical grounds.

It details how the military strategically targets low-income adolescents, identifying in particular those who are between 16 and 24 years old and come from households with an average income of £10,000. Military marketing briefs describe their teenage recruitment targets as “easily influenced” and having a “thirst for risk.”

The methods the military uses to sell itself to potential recruits are increasingly sophisticated and diverse, using social media platforms, TV and radio, search engine advertising, music and video streaming services and more, with the channels in play being connected and synchronised, and data driven.

The costs of these campaigns are high — total spend on marketing across all three services for recruitment purposes is over £27 million of taxpayers’ money per year.

While many young recruits will go on to have a successful and positive time in the military, there are major risks and complex considerations that are glossed over by recruitment campaigns.

Enlisting is a major life decision, particularly for adolescents and particularly if it means leaving mainstream education early.

Working-age veterans are twice as likely to be unemployed as working-age non-veterans, and many veterans complain of a lack of transferable skills when leaving the forces.

Recruits enter a uniquely challenging and intense environment which can have significant mental health repercussions, as demonstrated by recent concern over a suicide crisis among veterans and over the standard of mental health provision for the armed forces community.

The youngest recruits, especially if they have childhood adversity in their background, are the most likely to suffer long-term ill-effects. It means entering a different — and inferior — legal system. It means training to kill, and to risk your life.

While recruitment campaigns sell military life to teenagers as the ultimately fulfilling path, data on levels of satisfaction among personnel tells a different story.

Only four in 10 of non-officers are satisfied with services life in general, and would recommend it to others.

Only 36 per cent of personnel across the services feel their own morale is high and only 7 per cent feel the morale of the services is high.

Roughly half of recruits don’t feel they had an accurate picture of services life before joining.

One key message in military recruitment campaigns is that the forces are a welcoming, inclusive place.

Yet as demonstrated by the soldiers who racially abused the black female soldier who had become the face of the British Army Equality and Diversity campaign and who is featured in the army’s newest campaign targeting millennials, the progressive utopia they sell to young people is far from the reality.

There are high levels of bullying and sexual harassment in the military, with women and BAME personnel suffering in particular.

Legal charity Liberty recently launched its own Human Rights Helpline because the problems are so severe and the military’s own justice system is letting personnel down, with severe systemic failings including around investigating and prosecuting rape.

The military still needs to classify rape as a “very serious crime” so that it is investigated and prosecuted by the civilian police.

Currently, the military’s rape conviction rate is appallingly low. This is a striking contrast with the recruitment advert that last year told young women that they will be listened to more in the military than in civilian life.

The utopia of belonging and camaraderie sold in recruitment campaigns jars with the high levels of loneliness and isolation in the armed forces community, particularly among veterans.

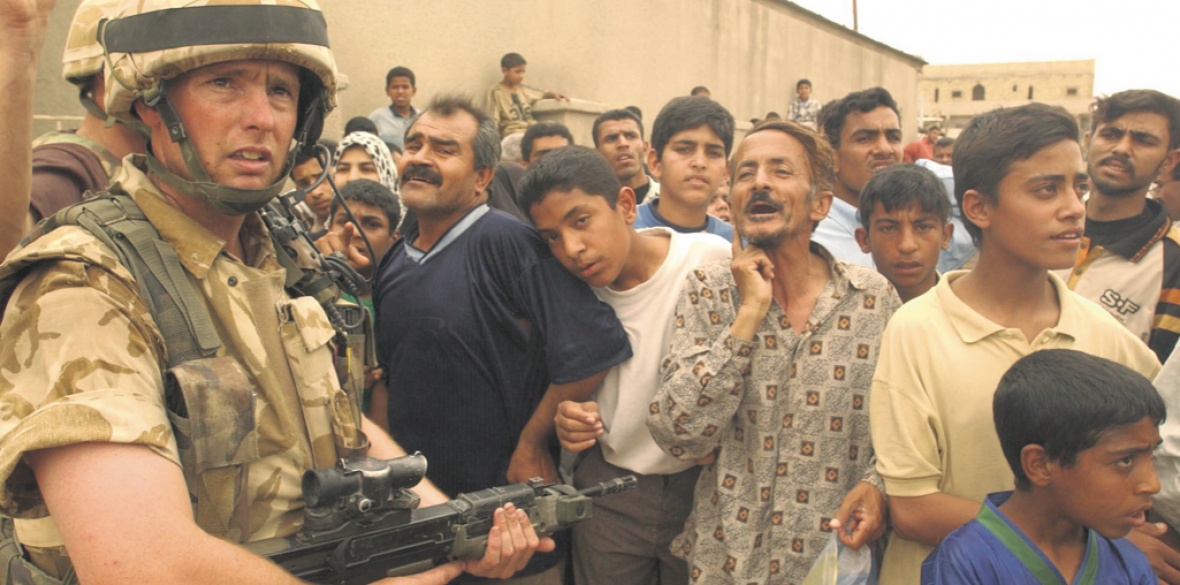

Military recruitment campaigns are misrepresenting vital information about forces life to vulnerable young people, and while doing so, they are also promoting self-development, fun and adventure in the context of war and armed conflict.

Academics Paul Hihgate and Nivi Manchanda write in the Selling the Military report: “We … should stop and think about the framing of a destructive force in wholly ‘constructive’ or ‘creative’ terms.

“The centring of ‘making’ people in these advertisements cleverly conceals the ultimate destruction of lives central to the use of military violence.

“In the US, a growing wave of employees in the technical industry are demanding that their labour is not used to further the ‘business of war’.”

Perhaps those working in the military’s chosen advertising agencies such as Karmarama and Capita, should likewise critically consider their role in selling the military to vulnerable young people.

Rhianna Louise is co-author of the Selling the Military report and works for ForcesWatch on education and outreach.