This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

LAST WEEK’S Ramblings on the young bearded vulture that toured Britain earlier this summer brought an email from a regular reader.

“Frosty,” it said, “why are you boasting about a beast with an eight-foot-something wing span when up here in the west of Scotland I often look up on a creature with a wingspan a foot or so bigger than that. No, I’m not talking about our golden or sea eagles.

“I’m a diver and the 3m (10ft) plus wingspan I’m talking about is on a fish. Why not tell our Star readers about the amazing skates and rays trying hard to survive on this beautiful part of our coastline?”

How could I resist? I’m not a diver and I’m a little embarrassed to say that my knowledge of skate mostly comes from eating it.

Skate and chips in paper or skate in black butter in a posh restaurant were both favourites of mine and my wife Ann’s.

I used to sing this Irish rebel song in Kilburn pubs in my youth: “’Twas down by Anna Liffey, my love and I did stray/Where in the good old slushy mud the seagulls sport and play/We got the whiff of ray and chips and Mary softly sighed,/Will you come along John, for a wan and a wan, Down by the Liffeyside.”

I’ve enjoyed this delicious food on the streets of Dublin on many visits.

In Britain all skate and ray species for eating are generally sold simply as skate.

In fact today true skate is not a sustainable catch and should be completely boycotted and banned from your plates.

Today the common skate is far from common — it is a very rare and much endangered fish.

Fishing for common skate is prohibited in EU waters. It is listed as critically endangered and as a threatened and declining species.

One hundred feet (33m) below the surface in western Scotland a small reserve has been established to give these huge fish a safer home.

Given such a place to live safely some may qualify for a telegram from the Queen.

I’m lucky enough to be blessed with a friendly and environmentally aware fishmonger.

She sometimes has ray — which she always labels skate — available from sustainable fisheries.

She usually has frozen wings and cheeks. Cheeks of these fish are called knobs, causing a few embarrassed giggles from customers not in the know.

To be absolutely sure, check that any skate you buy has the Marine Conservation Society badge of approval. Indeed that is a good tip when buying any sort of seafood.

One bonus when eating skate is that there are no little fish bones. Instead they have soft cartilage skeletons so you get one large sheet of bones like strips of leather from which you can easily peel the soft delicious white meat before flipping over the fish to do the same on the other side.

Here in Britain the terms “skate” and “ray” can be confusing, sometimes almost interchangeable.

What are traditionally named in Britain as rays are, scientifically skate.

Rays — be they spotted, small-eyed, cuckoo, blonde or many more — are actually skates.

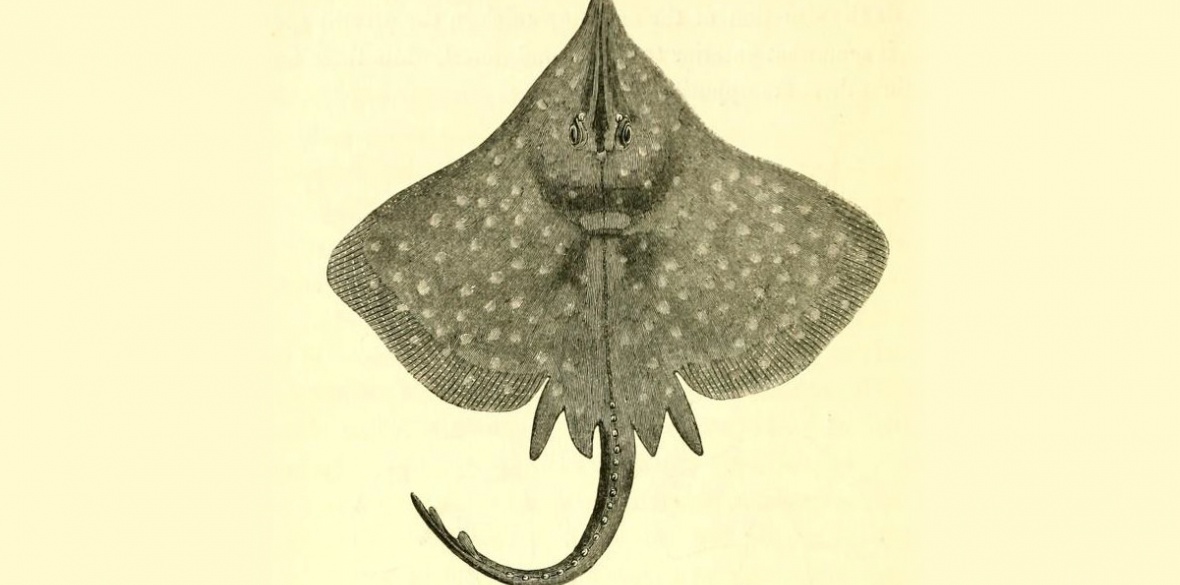

Both skates and rays are very closely related to sharks. They are flatter in shape and adapted to life on the seabed. Their mouth, nostrils and gills are on the underside, their eyes on top.

They spend much time buried in the sand, both hiding from predators and ready to ambush unsuspecting prey.

Of the 600 ray species worldwide, the largest is the manta ray with a wingspan of 12m (40ft). Some rays can deliver a powerful electric shock of up to 200 volts.

In 2006 Steve Irwin, the conservationist and TV film-maker known as the Crocodile Hunter, was killed while filming when he was stung in the chest by a stingray’s barbed tail.

My underwater reader from Scotland was talking about the rather confusingly misnamed common skate. It is also known as the flapper skate (Dipturus intermedius).

It is the largest skate — but not ray — in the world. Its wingspan can reach over 3m (10ft), a good foot bigger than my vulture.

Once really common all around the British Isles, the flapper skate has now been overfished almost to extinction.

It now only survives in some locations off the west Scottish coast where my reader stands on the sea bed 100 feet down and watches it swim over his head.

When it was really common some of these early skates were enormous. On the wall of a pub in Kent I once saw a faded sepia photograph of a small boy perched on the head of a giant skate like some sultan on an elephant’s howdah.

Using DNA testing, modern science recently discovered that what was called the common skate is in fact two different species, which are now known as the blue skate and the flapper skate.

It is these magnificent animals that my Scottish reader is lucky enough to be able to swim with.

The flapper skate is almost a yard across at birth after an 18-month gestation.

It eats mainly deep-water invertebrates and fish. It is dark olive green in colour and its wings have beautiful circular markings made up of pale spots.

These eye-like markings are known as a pseudo-ocellus and scare off fish predators.

As they mature, flapper skates change colour, with their upper body becoming more greyish-brown. Younger individuals are darker underneath, becoming lighter with age.

It is over 10 years before they reach sexual maturity, when females lay approximately 40 egg cases in spring and summer.

Known by beachcombers as mermaid’s purses, these egg capsules are very large, but the same shape as the far more common smaller ones.

Flapper skate egg cases vary between 10-14cm (6in) wide and 13-24cm (5-9in) long.

These giant egg cases can commonly be found on Orkney and along the west coast of Scotland.

The flapper is just one of nearly 20 species of skates and rays that are regularly found in British waters.

Some of these larger skates have become some of the most threatened species around our coast.

They are particularly vulnerable because they grow very slowly and are late to mature.

Buried in the sand on the sea bed, a single pass with a bottom trawl net can destroy that particular habitat forever.

If you are lucky enough to be able to get to the coast for any of your lockdown walks there is something positive you can do to help these magnificent animals survive.

Lookout for skate egg cases that often get washed up on the beach and can be found among the seaweed in the strandline. They come in all sorts of amazing shapes and sizes.

Send a picture of any you find with a scale in the picture to show its size and full details of where and when you found it to the Shark Trust.

They will use your sighting to help conserve all kinds of skates, rays and sharks. Here is the link: recording.sharktrust.org/eggcases/record.

The Shark Trust website (sharktrust.org) has PDFs of reporting forms with and egg case identifiers and other pics.

Hang on, I have to go now. There is a reader on the phone wanting to know why I haven’t written about the 9m (30ft) wingspan pterodactyl he found nesting on his allotment...