This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IT’S A surreal experience watching the leader of the opposition put a match to the research to which you’ve dedicated a lot of your adult life — and use your own phrases to do it.

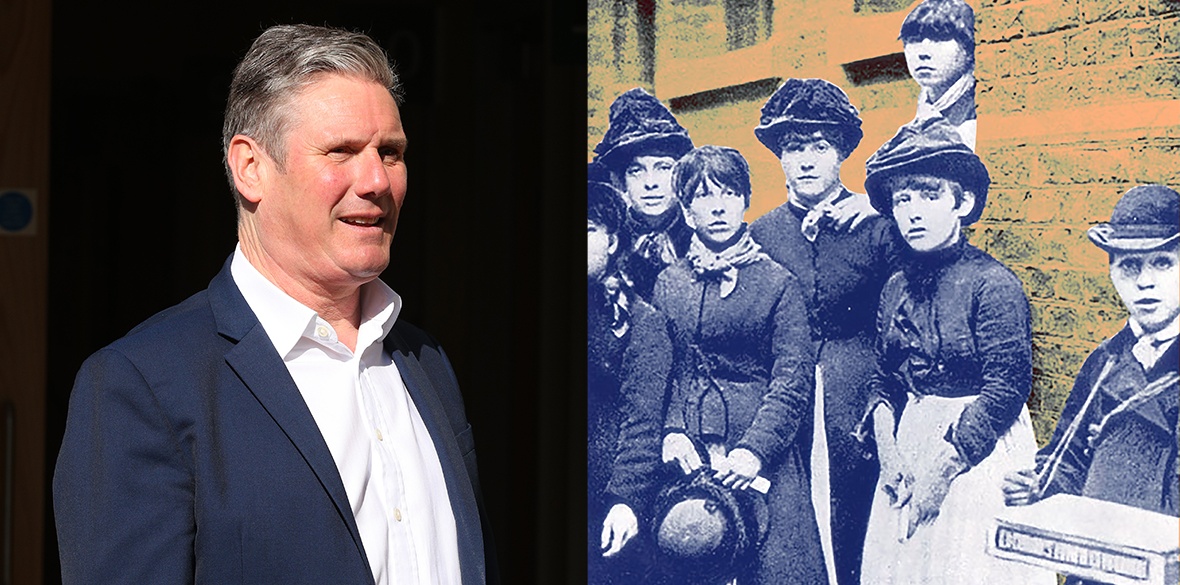

That’s what happened a few days ago when Keir Starmer and some Labour MPs put out a tweet celebrating the 150th anniversary of an 1871 protest against a proposed match tax, calling it a collective victory by workers which had “galvanised” other factory workers.

It’s hard to overstate how wrong he has got this; levels of error which raise questions not just about his team and their due diligence processes, but Starmer’s understanding of the events which created his own party.

The matchmakers Bryant & May were one of the worst employers in Victorian Britain — and it was a crowded field.

They didn’t just use child labour but were outraged when people suggested they shouldn’t, referring to the 12-hour shifts in toxic surroundings as “like play” for the child matchmakers, and suggesting that eight was “a very good age to start work.”

Bryant & May also knowingly exposed workers to white phosphorus poisoning, which caused a horrendous necrosis that ate the jawbone of sufferers while they were still alive (“phossy jaw”), causing suppurating and foul-smelling abscesses through which bits of dead bone worked their way out.

The employer refused to take safety precautions or use readily available safe alternatives.

In 1871, Bryant & May opposed the government’s suggested tax on matches, because they feared it could harm their business.

They produced a petition for Parliament and, in a clever PR move, decided to rope in their youngest workers to present it.

They told the children to take the petition to Parliament, giving them a day off.

These young people, with no trade union or job security, would have had no choice but to comply.

Matchmakers were slapped and struck by foremen or sacked for the smallest infraction — laughing, talking, having dirty feet.

That’s not to say they wouldn’t also have jumped at the chance of a day off out of the poisonous fumes as well, or that Bryant & May hadn’t persuaded them their own jobs might be at risk from the tax.

But something you do at the behest of your bosses is the very opposite of “collective action.”

The employers also exposed these young matchmakers to police violence. In those days, any poor-looking person out of their “place” in the East End could attract abuse and even violence.

Sending a huge procession of ragged children into “posh London” and the environs of Parliament had exactly the effect that could easily have been predicted — police attacked and kettled the youngsters.

The employers sent no monitors with the procession to protect it and were nowhere to be seen when this happened.

Because of this police brutality the procession never made it to Parliament, though the workers fought back with gusto.

The match tax failed ultimately because of intervention by Queen Victoria, among others, who believed it might be bad for the economy.

Bryant & May was a huge economic player and government was eager to protect its interests at all costs.

Bryant & May’s reluctance to stop using white phosphorus would later be the reason Britain — to its eternal shame — initially refused to sign up to the Berne Convention banning the poison.

Starmer’s second claim that the tax protest “galvanised other groups of workers” is not only completely wrong but makes no logical sense — the proposed tax was on matches.

It had nothing to do with any other industry. It would be interesting to know where he got the phrase from, however as it’s one I often use to describe the effects of the matchwomen’s strike 17 years later.

Continued maltreatment by Bryant & May led the matchwomen to walk out of their Bow factory in the summer of 1888.

These very poor working-class women, dismissed as the “lowest of the low” and from discriminated against Irish and Jewish communities in the East End, took on employers who had become so rich from the women’s labour they lived in vast country estates, and so well-connected they entertained Liberal politicians there.

The women should have been completely outmatched but, through their courage and determination, they won — a tremendous victory which led to the formation of the largest union of women and girls in the country at the time, influenced tens of thousands of other workers across the country and beyond, and led to the New Unionism movement, from which the Labour Party eventually came.

It has taken me 25 years to work on rescuing the Bryant & May strike from the “enormous condescension of posterity.”

When I began this as a trade union steward, the strike was incorrectly believed to have been led by middle-class socialist Annie Besant, and therefore was not generally considered to count as a valid, worker-led action, or one which could have significantly influenced others.

As a trade unionist involved in strikes, I doubted the orthodox version of events — it simply made no sense to suggest a middle-class “lady” the matchwomen didn’t know could have ordered 1,400 of them to go on strike for her own political aims.

Research soon proved the opposite was true — Besant was actually opposed to the strike.

The women had gone on strike before of their own volition, including in 1884 for the great socialist demand of an eight-hour working day.

Over the next few years I worked against academic condescension (I was accused of romanticising “illiterate teenage girls” and the London Irish community, who were too uneducated to be political — this was, of course, nonsense) and with grandchildren of the matchwomen who I managed to trace, I showed that this was a tremendous working-class victory.

I was able to prove Besant, although she helped the women with publicity, did not “lead” it or, at first, even approve of it: the strike was purely worker-led by a democratic and equal band of working-class women who had no “leaders,” just sisterhood, solidarity and working-class pride.

At a time when we are so deliberately cut off from our working-class history and achievements, I believe it is essential to put lessons of victories like this one to use — I teach it and other crucial events in working-class history in schools and on history courses, and have established a not-for-profit festival in the East End which runs annually (in non-pandemic years!) to celebrate the women and encourage a new generation of activists.

My findings have twice been discussed in Parliament and to my delight, I was able to take matchwomen’s descendants like the wonderful and sadly missed East End historian Ted Lewis (grandson of matchwoman Martha Robertson) to hear the women, despised in their day as a “rough set of girls,” at last celebrated as they deserved.

I presume Starmer was around when these debates took place — a number of his colleagues were certainly present, and the transcripts are available to read in Hansard.

In 2017 Jeremy Corbyn released a short video about the strike, featuring MP Lyn Brown, who has been extremely supportive of my work, discussing the importance of the women’s true strength and courage.

Corbyn acknowledged my findings that the matchwomen’s strike did indeed inspire many other workers other and laid the foundations of the movement which ultimately led to the birth of the Labour Party.

However a few years ago I offered assistance to a new campaign by descendants of one particular matchwoman, and things quite quickly went south.

After dedicating a fair amount of time and opening my contacts book to them, I received complaints from people I had put them in touch with, including a female Labour MP, about the campaign’s behaviour and treatment of those who had volunteered to help them, and also about their political objectives.

They appeared to be interested in celebrating just one woman, their ancestor, claiming she was a leader of the strike, and raising money.

After all my efforts to show the matchwomen were wonderfully autonomous and leaderless, this was disheartening.

I had to step back.

It was been frustrating to see the strike dragged back to an event led by individuals rather than a collective; and back to the nomenclature of “matchgirls” rather than women (although the workers sometimes referred to themselves as girls, according to Victorian conventions, I chose “women” because many were older and married, and also as a mark of respect — they were all living adult lives and earning their own wages, and “girls” just played to the idea these were frail waifs unable to act for themselves. No-one calls the 1889 dock strikers the dock boys!).

The campaign drew on the goodwill I had spent years working towards and people often assumed I was associated with it.

I had tried to refrain from any public comment, however, reasoning that a spat over labour history was rather unedifying as well as uninteresting to most people.

But Starmer’s avowal of their latest campaign celebrating an employers’ victory is a step too far.

It seems telling that Starmer has chosen not to consult the historian of the strike — perhaps because I’m a socialist — and that as leader of the Labour Party he apparently knows so little about labour history and the people who put him where he is today.

Louise Raw is a historian and author of Striking a Light (Bloomsbury) on the 1888 matchwomen’s strike and organiser of the annual London Matchwomen’s Festival.